Turned Away

Latinx COVID patients say they are not being taken seriously by the healthcare system. What's going on?

Keny Murillo could not believe what he was hearing.

It was the morning of June 23. The 26-year-old medical interpreter had taken his father, Saul, to a Durham hospital with shortness of breath, a cough, rising blood pressure, and low oxygen levels less than an hour ago. These were classic symptoms of a worsening case of COVID-19, and other people in the family, including Keny himself, had recently suffered their own battles with the illness. Now, the same hospital was calling and saying Saul—who doesn’t speak English, and was communicating through one of the hospital's interpreters—was well enough to go home, and that Keny should come pick him up. Something was wrong.

Keny and Saul Murillo are just some of the tens of thousands of Latinx North Carolinians who’ve contracted COVID-19. As of July 20, Hispanic or Latinx people constituted at least 43 percent of North Carolina’s more than 100,000 COVID-19 cases, despite making up just around a tenth of the state’s population. That number could even be an undercount; ethnicity isn’t known for more than 35,000 of the state’s cases, according to the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS).

But it’s not just the high rate of the coronavirus among Latinx people that worries public health experts. At a press conference last week, Viviana Martinez-Bianchi, a Durham doctor and adviser to the NCDHHS, said she’s heard complaints from the Latinx community that people are being sent home from the hospital despite being sick enough, in their view, to be admitted.

Saul Murillo was very nearly one of those people. By the time he contracted COVID, the virus had already ripped through his family. Along with Keny, Saul's wife and daughter (a physician visiting from Honduras) and his two grandsons also came down with COVID symptoms. But it quickly became clear Saul’s illness was worse. He had developed a cough, and Keny’s sister couldn’t hear his right lung when she tried to listen with her stethoscope, suggesting a potential lung collapse. Earlier that morning, around 5 a.m., Saul’s oxygen levels had dropped to dangerously low 89 percent.

Dropping Saul off at the emergency room was one of the hardest things Keny had ever had to do in his life.

“It just hurts your soul,” he said in a recent interview. “The sense of helplessness knowing that I couldn’t go in with him.”

Too anxious and distraught to immediately go home, Keny stopped at a gas station to go for a walk and collect his thoughts. That's when his phone rang. Someone from the hospital—Saul told Keny it was a nurse—explained to him that his father’s oxygen levels were 93 percent, much higher than it had been a few hours earlier. The hospital was going to discharge him. (The hospital isn’t being named at the family’s request,)

“I was shocked, I couldn’t believe it,” Keny said. “I said to her, ‘If oxygen levels were 93 at home, I wouldn’t have brought him in.’”

After a tense back and forth, Keny said he began to dig deeper into what the hospital had actually done, and wasn’t reassured.

“I asked her if she’d listened to his lungs. She said she hadn’t gotten there yet,” he recalled. “I said, what is his blood pressure?” Saul’s blood pressure was 157 over 98, which the American Heart Association defines as a stage 2 hypertension, one step below crisis levels.

“I don’t feel so good,” Saul told Keny in a phone conversation. “They had me walk a little distance and I felt like I wasn’t going to make it.” Saul was also starting to suffer from a headache and could feel numbness in his arms. In Keny’s view, he was quickly deteriorating.

For whatever reason—be it Keny’s advocacy for his father or Saul’s clearly worsening state—the hospital never discharged Saul, and decided to admit him for two nights for observation. And at first, things did not get better: on June 25, he was transferred to the ICU and the doctors told the family they were going to intubate him. (During his stay in the hospital, Saul tested positive for COVID-19.)

“His voice was so weak, we could barely hear him and could sense how scared he was,” Keny recalled of the last phone conversation before his father was intubated. “We did a really quick prayer. We just put everything in God’s hands.”

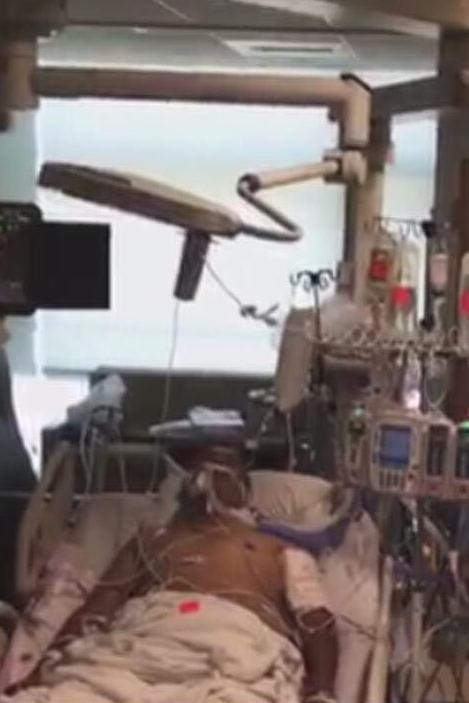

Saul Murillo in the hospital. Photo courtesy of the Murillo family.

Saul Murillo was lucky. He was intubated until July 1 (many COVID-19 patients are intubated for more than a week or longer) and was moved from the ICU to a regular room on July 5. He was discharged on July 9, more than two weeks after he first entered the hospital. Keny said that his father is slowly but surely starting to get better and regain his strength.

Keny has turned the scenario over in his mind, and he’s mainly relieved that he was the one the hospital decided to call to pick his father up that night.

“If they had called my mom and told her through the interpreter to pick him up, my mom would've been delighted and thrilled [and would have picked him up],” he hypothesized. “The next day he would’ve gotten worse to the point where we had to call 911 or risked him not making it to the hospital.”

Health inequities along racial, ethnic, and class lines have always existed in the United States. More than one in five Latinx people in the United States were uninsured in 2018, twice the rate of the non-Latinx population, according to the CDC.

The pandemic has simply made these systemic faults impossible to ignore. The numbers are stark in North Carolina: in Wake County, Hispanic or Latinx people made up 44 percent of the state’s 9,000-plus cases as of July 21; in Orange County, Hispanic or Latinx people made up 30 percent of cases (the ethnicity was unknown in 26 percent of cases); and in Durham County, the hardest hit of all of North Carolina’s most-populous counties, Hispanic and Latinx patients constituted 61 percent of COVID-19 cases despite making up just 14 percent of the county’s population.

Some, such as U.S. Sen. Thom Tillis (R-NC), have tried to explain these numbers away by framing the issue as one of personal responsibility. “We do have some concerns that in the Hispanic population we’ve seen less consistent adherence to social distancing and wearing a mask,” Tillis said in a telephone town hall last Tuesday.

Tillis’s statement is tinged with racism. But it also ignores the many complex factors driving the virus’s racially disproportionate impact, as Martinez-Bianchi explained in a phone interview. She serves on a state DHHS task force and co-founded Duke’s Latin-19 COVID-19 advocacy group in March, a coalition of doctors, researchers, and other community members advocating for the Latinx community in its fight against COVID-19.

“A lot of Latinos are essential workers,” she said. “A lot of them continue to go to work in meatpacking, construction, and [other workplaces] where COVID-19 can be easily transmittable where people work too close together.”

Another issue, Martinez-Bianchi said, is that the concept of isolating with “family” doesn’t always mean the same thing. “In the Latino community, that may mean the whole extended family. Mom, dad, kids, auntie, grandma, many family members living under the same roof,” she said. And, of course, people with fewer means sometimes aren’t able to isolate themselves, especially “in a 700-square-foot apartment where six people are living.”

Martinez-Bianchi has had to reassure people who are worried that COVID-19 patients only go to the hospital to die—an understandable fear, given the horror stories that have come out of hospitals during the pandemic. (Keny Murillo said he has had similar conversations.) Martinez-Bianchi recently spent hours on the phone with a Guatemalan-American patient who was refusing to go to the hospital because he had only recently received his citizenship papers and was able to bring his two children to the U.S.

“This is the first time I’ve had my two children with me,” she said he told her. “I’d rather die at home with them than at the hospital.” She said she was ultimately able to convince him to go, but added: “There are thousands I haven’t spoken to.”

During a press conference last Thursday, a Telemundo Charlotte reporter told Dr. Mandy Cohen, the head of the state Department of Health and Human Services, that they had received “multiple allegations” that immigrants were being denied care for COVID-19 symptoms at hospitals due to a lack of health insurance.

The Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act, or EMTALA, was passed by Congress in 1986 and requires emergency departments to treat anyone who walks through their doors. It is also an unfunded mandate, and so studies in recent years have indicated that the problem it was responding to, known as “patient dumping,” is still happening in American hospitals, albeit in a less transparent fashion.

Cohen reiterated in the press conference that emergency rooms are required to treat people under federal law, but said, “We do know that there are access issues for folks who don’t have insurance.”

The Spanish-language North Carolina newspaper Qué Pasa reported recently that one essential worker, a construction worker in Alamance County, was denied a COVID-19 test from a CVS because he didn’t have a Social Security number or a driver’s license, contrary to the state’s guidelines. Another woman told the paper that it took three tests and two hospital visits for her to find out that she was positive.

These reports are not just limited to North Carolina. The New York Times reported in April on a 65-year-old Latinx man who went to three New York-area hospitals before finally being admitted to the third. By then, it was too late to save him. In May, the Des Moines Register reported a 54-year-old white man had died under similar circumstances.

Martinez-Bianchi, who serves on the DHHS’s Task Force on Historically Marginalized Populations, said she had even heard stories of people being “dropped [off at] the hospital and if they didn’t have a culturally appropriate interpreter, they were overwhelmed by the questions and told they weren’t sick enough.”

Martinez-Bianchi said there were a few different potential scenarios that might lead someone to be turned away at the hospital. One is that someone who had COVID-19 genuinely didn’t need to be hospitalized even though they felt sick, which has been a problem throughout the country, as even “mild” COVID-19 cases (such as Keny’s) can lay the person who’s suffering from it out for weeks, and continue to impact them after the primary symptoms of the disease have disappeared.

But someone might also be sick enough to be hospitalized but get turned away, either because their pain isn’t being taken seriously or because of language and cultural barriers that are preventing them from advocating for themselves.

If someone is being turned away due to a lack of health insurance or a perceived lack of health insurance, Martinez-Bianchi said, “that’s horrifying.”

Dr. Leonor Corsino, an endocrinologist and associate professor of medicine at Duke who is on the leadership team at the university’s Center for Research to Advance Health Equity (REACH), has spent much of her career studying bias in healthcare. “[One] way I’ve seen this is that providers will make assumptions [about] the patient’s ability to pay for medication,” Corsino said in a phone call last week. “They assume you don’t have insurance and consciously or unconsciously make recommendations based on their assumptions.”

In emails, the public health departments of Wake, Orange, and Durham counties said they hadn’t received reports of sick Latinx people being turned away from hospitals, though the same sort of perceived language and legal barriers that sometimes complicate the decision to seek healthcare exist in the bureaucracy as well.

The state Department of Health and Human Services said in a statement that as part of its outreach efforts, it’s hired 480 contact tracers with roughly half of them being bilingual, “with a focus on Spanish speakers.” The agency also said that complaints submitted to its Division of Health Service Regulation (DHSR) don’t indicate that Latinx people are being disproportionately denied care in emergency rooms, but that “nevertheless, DHSR seeks to include these individuals of Latin American origin or descent in its sample of cases when conducting an EMTALA complaint investigation.“

“The issue boils down to systemic racism,” Orange County community relations director Todd McGee said in an email. “The discriminatory rules, policies, etc. that make up our society are ones that we often don’t think about because they have become so ingrained in our society.”

If there’s any silver lining to this crisis, it’s that long-ignored inequalities in healthcare are finally coming to light.

Corsino said that REACH is working on a project to try to help providers acknowledge their implicit bias and change their behavior, though she acknowledges this is a controversial proposition.

“It takes a lot of effort [to change behavior] and there hasn’t been a lot of research on how we can do that with implicit bias, so a lot of new information will emerge from this project,” Corsino said.

On a more systemic level, Corsino’s helping with a proposal to offer advanced medical Spanish as part of Duke’s curriculum so new doctors can “freely communicate with their Spanish-speaking patients without the need of an interpreter during the visit,” as well as another proposal to offer a Spanish-language version of Duke’s electronic records and communications system for patients.

At the local level, Wake, Durham, and Orange all said they’re working with local community groups, organizations, and businesses to educate and communicate and engage with Latinx, immigrant, and refugee communities about COVID-19 and its effects.

“These community partners are also well trusted in the community and this is incredibly important because public/government offices have a history of discriminatory behavior, we are trying to make sure that people know that they can trust us,” McGee acknowledged in an email.

Statewide, the NCDHHS awarded grants to five different nonprofits, advocacy groups, and media organizations in late June. Earlier this month, the NCDHHS pledged to deploy up to 300 free testing sites targeted to Latinx, Black, and indigenous communities that have been especially impacted by COVID-19. The state also launched a website last week to help Spanish speakers decide on whether or not to get tested for COVID-19 and to monitor their symptoms.

While Martinez-Bianchi says she’s conscious about the problems that could be caused by providers speaking out against inadequate conditions in their facilities—doctors and nurses all over the country have been alleging retaliation by their employers almost since the beginning of the pandemic—she believes it’s time to survey healthcare workers so the task force and the state can understand the “depth and seriousness” of the problem.

“Just like how we survey for personal protective equipment, we should start surveying health workers about the care being provided to people,” she said. “How do we convey to administrators what not providing care to people means? Why didn’t we put more testing in the middle of Black and Latinx communities? Why didn’t we start with free testing? This is part of the complexity of working with pandemic response.”

In a photo provided by the Murillo family, Saul lies in an ICU hospital bed hooked up to a ventilator. He’s unconscious. What seems like dozens of wires plug in and out of his body keeping him alive.

“People should see this is no joke,” Saul told Keny in Spanish. “This is serious.”

Correction, 10:29 a.m. ET: This post initially described Dr. Leonor Corsino as an assistant professor at Duke and the leader of the university’s REACH center. In fact, she is an associate professor and part of a broader leadership team at the center.

This piece was published as part of a content partnership with INDY Week.

Art: Annie Maynard/INDY Week

There is a small, but at least universal part of contemporary medical training that has doctors and nurses in residency learn what can be sugarcoated as something like, "cultural differences in perception to pain". The last one I saw was printed in 2017 and read like a 1930's German Ethnic Recognition Field Guide. I have had more than one Physician tell me that Hispanic or Latinx people are widely expected in the medical field to exaggerate pain. I'm no medical expert but I was absolutely floored to hear it at the time and, unfortunately, none of this article surprises me now. Not sure how much of that training might focus on the things you pointed out here but my guess is little to none.

Thinking on better condition of medical help for latinx will help to safe lives.That' s way assuri g their comunication is vital.