This Fight Did Not Begin With Us And It Will Not End With Us

We know the right to abortion can be won because it has been won before. Now it’s up to us to win it again.

I’ve spent much of the last week thinking about moms—my own and many others. I’ve thought a lot about non-moms too, to be honest—“moms” really serves as a catch-all for anyone and everyone who fought for the right to abortion access in America decades ago, and all those who fought for it for many decades before that.

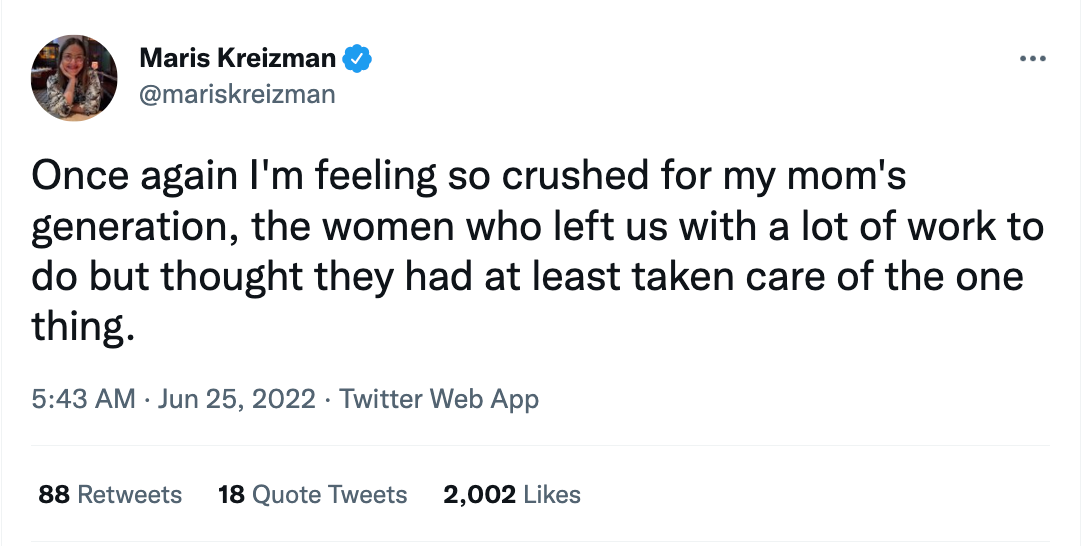

I’ve been channeling (or maybe diverting) my sorrow toward the past. I know I’m not the only one.

Since Roe v. Wade was repealed a week ago, I’ve cycled through states of rage, sorrow, alarm, and many, many other micro-feelings. But hanging over it all has been an awareness of the historical weight of this moment, and the centuries-long battle over reproductive rights that preceded it. It’s not just that this news is unspeakably horrifying. It’s that we’re experiencing a very specific regression, a very specific undoing, and a very specific loss. It felt, and continues to feel, a bit too much like a funeral—one in a brutally long line of civic memorials we’ve attended over the last several years.

Last Friday, as the texts and calls ebbed and flowed, I reached out to a friend of my mom’s who I’ve known my whole life. We exchanged a few desperate messages, talked about other things, and made necessary gestures toward hope. It was the best we could do.

She wrote: “It’s shocking to have people quoting 17th-century texts to explain why women have no rights to govern their own bodies,” and later: “Is it too much to ask your generation to help repair all the bullshit that my generation caused?”

I tried several times to come up with a direct reply, but the question was beyond me.

Other friends have said their calls with their moms that day ranged from low-key hysteria to variations on “yes this is hell, now we have to get to work” or most often, some combination of both.

It’s in this context that I keep returning to the history of the struggle for abortion rights in this country—the history, in other words, of the “work” that our mothers have been talking to us about over the past few days. This history has strangely become my source of sanity as the reality of our situation has set in. It’s an odd solace—especially as it’s so clear that the justices who made this decision for us hold this legacy in contempt—but it has made me feel connected to all of the people who refused to accept that there was nothing they could do but cave to their oppressors, and who forced the world to change over and over again. It has made me remember that we will win the right to legal abortion once more, because we’ve done it before.

Some brief context: Abortion was frequently practiced in this country in the 17th and 18th centuries. During the 19th century, abortion wasn’t just legal and available in the United States. Abortion drugs and procedures were openly advertised, and fetuses generally weren’t regarded as a person until “quickening,” when a pregnant person could feel the baby kick. (Despite all this, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote in his opinion that abortion is “not deeply rooted in the Nation’s history and tradition.” Justice Samuel Alito did it too. Such assertions are either proof of ignorance or an outright lie aimed to gaslight the country and further pave the way for the court to chip away at our rights on things like contraception and same-sex relationships, all under the demented guise of some sort of return to form. It’s a desperate touchstone, and proof of just how useful it can be to rewrite the past when you don’t have the will of the people on your side.)

Access to abortion only started to change over time because of anti-abortion movements like the “Physicians’ Crusade Against Abortion” and the Comstock Act of 1873, which criminalized sending “obscene, lewd or lascivious,” “immoral,” or “indecent” materials through the mail. This was interpreted to include information about contraception or abortions. Slowly, states started to outlaw the practice, and by the turn of the 20th century, abortion was illegal in every state.

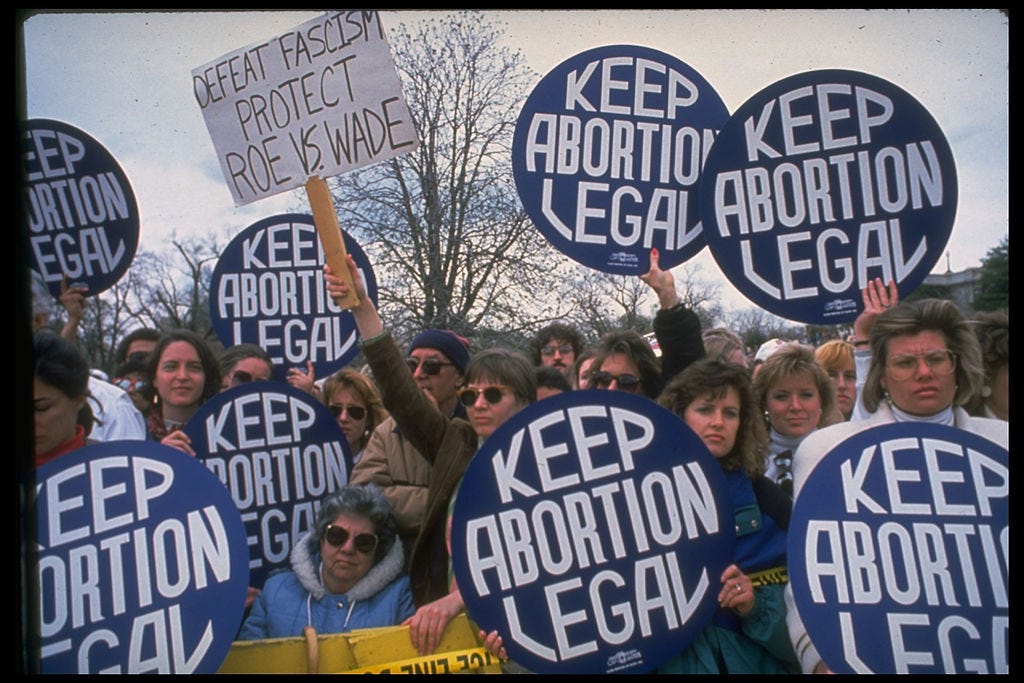

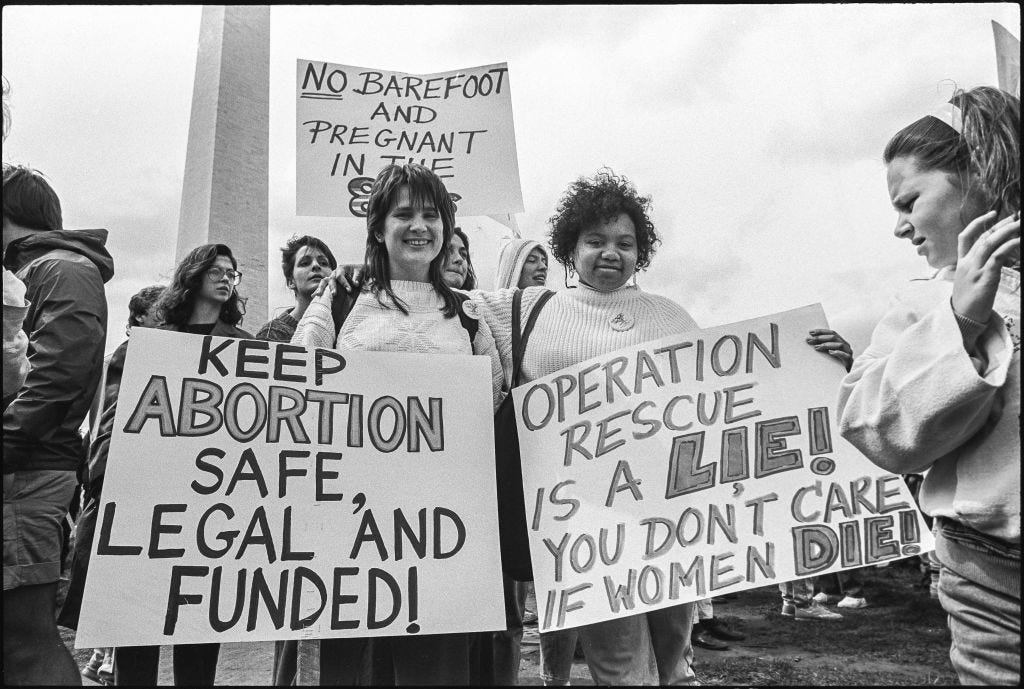

It took roughly 60 years (!!!) for things to begin to swing back with the dawn of second-wave feminism, and it took relentless, ongoing efforts to get there. Throughout the early 20th century and especially during the Great Depression, abortions still occurred in significant numbers, but in secret, leading to thousands of deaths a year. In 1921, Margaret Sanger founded the first iteration of Planned Parenthood, called the American Birth Control League, and decades later in 1955, the organization held a conference called “Abortion in the United States,” which included testimonies that spurred a broader national conversation about abortion rights. Things finally started to take a significant turn toward the end of the 1960s, as the feminist revolution wrenched women’s right to bodily autonomy into the political spotlight. Groups like Chicago’s Jane Collective, San Francisco’s Society for Humane Abortion, a coalition of rabbis and pastors called the Clergy Consultation Service on Abortion, and the Association for the Study of Abortion all sprung up to help people get abortions in defiance of the law. The 1966 trial of the San Francisco Nine, a group of doctors who were sued for performing abortions on women who’d been exposed to rubella, put a national spotlight on the issue and fueled a portion of the medical community to band together and speak out about performing safe abortions.

These achievements are significant, but they are mere bullet points on the timeline of progress, set in relief against countless smaller acts of retaliation, organizing, and communicating that ushered in a larger change in public opinion and the law.

Eventually, governments began to act. In 1967, Colorado became the first state to decriminalize abortion in certain cases. Other states soon followed and in 1970, Hawaii became the first state to fully legalize abortion, allowing a woman to have one “simply because she did not want to have a baby.” Three years later, Roe v. Wade made abortion legal in the entirety of the United States.

I find myself focused on this series of events—and what came after—as I’ve tried to see a path forward. It took decades to criminalize abortion, decades to legalize it, and decades to criminalize it again. That fact is maddening and disheartening in many ways, but I’m trying to also find some hope in it. As I mourn for the work that has been lost, I’m also grateful for it, because it provides a framework, a guidebook, and a proof of concept. The fight for a better, safer, more inclusive, more progressive world is a long game effort. It began long before us and will continue long after. The suffrage movement took almost a century, the movement against apartheid in South Africa took decades, as did the abolition of slavery in the U.S., as did the right to same-sex marriage in the U.S. Most social reform movements are impossible to quantify in years—the fight for civil rights and labor rights are eternal, and sweeping social change, especially the kind that protects anyone who’s not a cis white male, is never-ending. Most require radical protests and violence.

This broader perspective isn’t meant to take away from the hell of the moment or the very real danger people are in, or the very important work activists, lawyers, and health care providers are doing to help people now. This moment is our moment, and in many ways it’s all we have. But the hard-fought struggles of the past are worth examining in the face of despair. It doesn’t help the horrors, the injustice, or the fear, not really, but it can be a reason to keep going. The battle for abortion rights began before us and will outlive us all, and envisioning what comes next means having to think about the world outside our immediate experience, and outside of our lifetimes. And isn’t the betterment of the collective—present and future—the entire point? Someday, if we’re lucky, we will be the figures of the past who fought when it seemed as though all was lost.

So, what does come next? I don’t know, but it will almost certainly get worse than it’s ever been before. We know that anti-abortionists will lie, cheat, steal, and kill, and the people who are purportedly on the pro-abortion side often shrug their shoulders, backpedal, or actively work against it, time and time again. There’s precedent for the fact that progressive eras follow authoritarian ones, and that maybe this is part of a broader pendulum swing, but that’s only true if we make it so. Activists saw the repeal of Roe v. Wade coming years ago. Progressive movements take years, but so do conservative ones. This is a war that will go on and on. The arc of history will only bend toward justice if we bend it, and we’ve arrived at the point when there’s very little left to lose. We’re literally being told to “vote!!!” as recourse for a government that wants us to shut up or die. We’re living in a moment where companies are having to step in and help secure abortions—and even then only sort of and/or if you sacrifice other rights. That’s not a reality we should accept.

There are new problems to contend with, of course—namely tech, privacy, and surveillance threats. There are old ones—white supremacy, patriarchy, and capitalism—that will never die, or at least not anytime soon. And there’s the problem with the Supreme Court itself, which is a death cult that must be destroyed ideally or fundamentally changed at a minimum. There’s so much work to be done. It’s overwhelming. And while this blog is adamantly against hagiography and against glorifying the past, as we hurdle toward new territories of bleakness, I find myself bolstered and encouraged despite my hopelessness because of the words and actions of people who came before. In the anguish of the last week, I’ve found myself rereading quotes from socialist activist Eugene V. Debs, who died almost 100 years ago and all those years ago could clearly see the court for what it is:

Who appoints our federal judges? The people? In all the history of the country, the working class have never named a federal judge. There are 121 of these judges, and every solitary one holds his position, his tenure, through the influence and power of corporate capital. The corporations and trusts dictate their appointment. And when they go to the bench, they go, not to serve the people, but to serve the interests that place them and keep them where they are.

Why, the other day, by a vote of five to four — a kind of craps game — come seven, come ’leven — they declared the child labor law unconstitutional — a law secured after twenty years of education and agitation on the part of all kinds of people. And yet, by a majority of one, the Supreme Court, a body of corporation lawyers, with just one exception, wiped that law from the statute books, and this in our so-called democracy, so that we may continue to grind the flesh and blood and bones of puny little children into profits for the Junkers of Wall Street. And this in a country that boasts of fighting to make the world safe for democracy! The history of this country is being written in the blood of the childhood the industrial lords have murdered.

One more because this king really got it:

“With every drop of my blood I defy their law, and I despise them. I am appealing to you, to the common people; I care nothing about the Supreme Court,” Debs said. “The Supreme Court is not the court of last resort; the people are.”

I find myself invigorated by the May ‘68 slogan “cours vite, camarade, le vieux monde est derrière toi” (“run fast, comrade, the old world is right behind you”), by the work of 19th-century abortionist Ann Lohman (better known as Madame Restell), by the work of Jane, by the innumerable and largely unheralded caretakers of those seeking illegal abortions through time all over the world. I find myself fueled by poetry, and even Instagram art, and by the words of all the moms and activists who’ve been ready for this, and are ready to fight again. I’m invigorated by the words of activist Mike Davis, who has been at it for decades, and still finds reasons to see the possibility of something better:

This seems an age of catastrophe, but it’s also an age equipped, in an abstract sense, with all the tools it needs. Utopia is available to us. If, like me, you lived through the civil-rights movement, the antiwar movement, you can never discard hope. I’ve seen social miracles in my life, ones that have stunned me—the courageousness of ordinary people in a struggle.

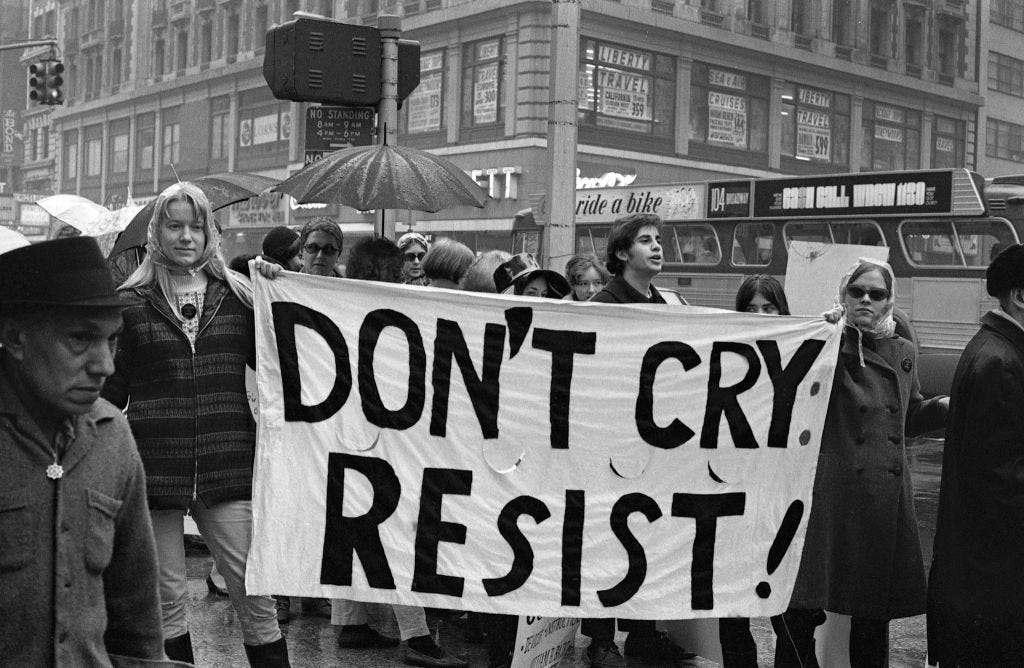

When I first started trying to write about this tragedy, I spent several days with a single line in a document: “How do you turn a scream into a blog?” I rested, I read, I despaired, I tried again, and I sat with the part of myself that is very tired and very despondent and very scared. I thought a lot about how part of the power of the fascists comes from inflicting varying shades of trauma on every single person whose life might suffer for it. It’s designed to tear people down and wear them down. It’s designed to make us so mired in panic about what’s happening now and what might come next that we’re debilitated. But knowing that only makes me more certain that the only way to move forward is as an agitator, just like the many agitators who came before. It is the only way. Donate, help each other, communicate, organize, disrupt, break laws, picket, disobey, and generally become ungovernable. No justice, no peace. Abortion without apology or clarification. They’re counting on us being tired, but they’re not accounting for the fact that rage is a hell of an antidote to fatigue.

We needn’t continue to participate in the forced mass delusion that this is a functioning system, that voting works, that the state operates to protect us. We are not the first ones to be oppressed, or to fight. It’s hard realizing that certain lessons don’t become ingrained in the human body, we have to relearn them, and we have to fight anew. It sucks, but at least there’s a precedent.

We know it can be done because it has been done before. Now it’s up to us to do it again.

And...I'm crying again. This is so well said and inspiring. Thank you, Caitlin.

This was fucking beautiful Caitlin thank you. This line in particular:

“They’re counting on us being tired, but they’re not accounting for the fact that rage is a hell of an antidote to fatigue.”

This spoke to me on a bone-deep level. The past few weeks have been exhausting, and finding the will to keep moving forward has been difficult. But as long as I keep my rage pure, I’m gonna do my best to keep up the fight.