The Secret Left-Wing History of 'Monopoly'

Behind the top hat and twirling mustache of Rich Uncle Pennybags is a tale of thievery, corporate greed, and the erasure of an anti-monopoly activist.

As pretty much any American board game player could tell you, the game of Monopoly begins at Go, ends in either domination or defeat, and probably includes a few rides on the rails or trips to jail in between. It’s usually a fairly straightforward journey, even if it often (okay, always!) takes way too much time.

The story behind the creation of Monopoly, however, is a different kind of trip altogether. Don’t worry: it’s also a long, arduous tale of money-grabbing, competing interests, drawn-out battles, and the bad guys mostly winning. But we’re gonna make it fun!! I promise.

Now, this wouldn’t be a Discourse Blog history—which we’re now calling Discourse University, by the way!—if we didn’t make it a wee bit quarrelsome, so in true contrarian fashion, we’re pointedly passing by Go and not starting at the beginning. Instead, we’re going to start with an ending—a death, and a recent one at that. Even the most online of you probably didn’t read about it, because it simply didn’t get that much coverage. I only found out about it because of a tweet from author Mary Pilon:

The tweet caught my eye for obvious reasons: Games? Love ‘em. A game about the ills of corporate monopolies? Sign me up!! But it also stood out because Monopoly is one of those cultural products, like say, Shakespeare and The Beatles, that is so deeply ingrained in the modern collective consciousness that it astounds me to think there was something I didn’t know about it, even if that something exists outside of the officially licensed universe of the game. Anti-Monopoly, the game referenced in Plion’s tweet, sold hundreds of thousands of copies (granted, a mere fraction of Monopoly’s hundreds of millions), but had never seeped into my cultural diet. Why?

To be totally honest, it didn’t take very much digging or much more than a second thought to realize that the very obvious reason I didn’t know about Anti-Monopoly was that Parker Brothers, the toy and game behemoth behind Monopoly, didn’t want me to. After Ralph Anspach, an economics professor at San Francisco State University, created Anti-Monopoly—which gamified monopoly busting versus monopoly building, and only sent monopoly holders to jail—back in the 1970s, Parker Brothers sued him for trademark infringement.

Information contained in the rules to the second edition of the game gives you some idea of why Parker Brothers might’ve been a little bit bothered: "In the real world, we're all in trouble when monopolists win because there is no second game to give consumers and competitors another chance. That's why Professor Anspach invented ANTI-MONOPOLY—to show in a fun way how our country tries to stop the monopolists with anti-monopoly laws."

The case dragged on for 10 years and had several twists and turns along the way, but when all was said and done, Anspach and Parker Brothers reached a settlement. Anspach won the right to make the Anti-Monopoly game, which you can still buy to this day. There is one twist I must note though, which is that Parker Brothers quite literally and very publicly buried 7,000 copies of Anti-Monopoly in a landfill at one point during litigation. That’s how mad they were that they couldn’t have a monopoly on Monopoly. Those messy bitches!

On the subject of the suit, Anspach told Killscreen back in 2012, “In those days, just as now, people were really pissed off at monopolies. In the first year, we had orders for about a million games, and we had sold about two hundred thousand. And then the monopolists struck. Monopoly decided to sue me for trademark infringement, which began a nine-year battle in which Anti-Monopoly defended itself against Monopoly.”

Oddly enough, the original inventor of Monopoly probably would have been on Anspach’s side, and that’s where the story gets really interesting. It was during the fight between Anspach and Parker Brothers that Anspach, as a means of fighting back, traced the history of Monopoly all the way back to the beginning, and uncovered the kind of bad behavior that was all too fitting for the makers of a game about accumulating land, wealth, and dominance.

Fittingly, this shady origin story came with a self-generated myth, just like the ones invented by many a tawdry American capitalist. The official Monopoly story, which was actually included in the game for decades, was that it was the creation of Charles Darrow, an out-of-work salesman who created the game while trying to provide for his family during the Great Depression. Those facts are technically true, except that Darrow didn’t really invent Monopoly—he stole it after playing it at the home of some friends.

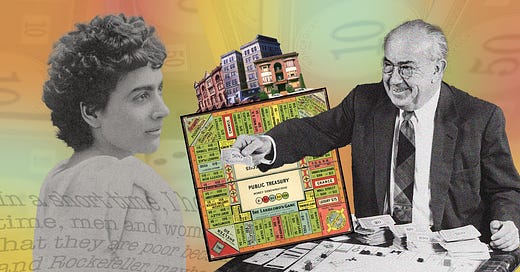

The game played that night was the spawn of an idea born decades earlier by an unmarried, financially self-sufficient, activist and feminist lefty named Elizabeth "Lizzie" Magie. Magie originally called it “The Landlord’s Game.” It was modeled in part after a game played by Oklahoma’s Kiowa tribe, and Magie imagined it as a tool for revealing the immorality of land-grabbing, and for teaching the principles of economist Henry George, who believed that profits from land ownership should be subjected to heavy taxation. She actually patented the game in 1904 (and again later in 1924) and published it, and it became relatively popular among Progressives, socialists, Quakers, and academics, especially around Washington D.C. The game was a social critique with two sets of rules—an anti-monopolist set in which everyone reaped the rewards of wealth, and a monopolist set which shares an ethos with the game we play today. The game taught players about injustice in land ownership and was meant as a kind of protest against contemporary monopolists of the time like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller, and if you’re not already fully on board with this woman, please read what she wrote in an issue of The Single Tax Review in 1902:

It is a practical demonstration of the present system of land-grabbing with all its usual outcomes and consequences … It might well have been called the ‘Game of Life’, as it contains all the elements of success and failure in the real world, and the object is the same as the human race in general seem[s] to have, ie, the accumulation of wealth … Let the children once see clearly the gross injustice of our present land system and when they grow up, if they are allowed to develop naturally, the evil will soon be remedied.

Magie’s high hopes were thwarted in part when Darrow modified and replicated the game, sold it to Parker Brothers, and readily engaged in the myth that he was responsible for the property. In fairness, the persistent problems of inequity in land ownership all over the world aren’t entirely Darrow’s fault, but on behalf of Lizzie Magie, he gets some of the blame today. He literally asked his friends to write down the rules for him before he sold the game!

Darrow would go on to make millions from Monopoly, while Magie made around $500 from Parker Brothers, a move that seemed to be more of a safeguard against litigation than an apology or righting of wrongs. Magie died in relative obscurity. It wasn’t until Anspach was fighting his own legal battle that her story became better known—this despite the fact that Magie herself tried to expose the truth, and that the real history appeared in print as early as 1936 in issues of The Washington Post and the Washington Evening Star.

She didn’t get the money, fame, satisfaction, or intellectual influence she wanted, but Magie’s story did help Anspach win his case and expose what he called “the Monopoly lie.” It was her game and Darrow’s thievery that helped Anspach argue that the Monopoly title was in the public domain.

Obviously, all of this would feel better now if Monopoly had experienced some kind of spectacular fall from grace or a major rehaul or had been the subject of a major motion picture (seriously, we made a movie about the guy who started McDonald’s but there’s no adaptation of this???). The story has faded from popular consciousness, and any chance at real retribution is largely lost. To this day Parker Brothers and parent company Hasbro still “credits the official Monopoly game produced and played today to Charles Darrow.”

In a history full of ironies, the greatest of all is that Lizzie Magie’s vision for a teaching tool against monopolies became a bestselling proponent of them. It’s a good thing to remember to add to your list of reasons for declining the next time someone asks you to play the game.

This post is part of Discourse University, an occasional series where we tackle history, ideas, and any other wonky kind of thing that strikes our fancy.

Looking forward to football season and the Discourse University vs. University of Austin Thanksgiving rivalry game!

Wow this is probably my favorite discourse blog post so far!

Lefty ideas co-opted to reinforce the status quo? Every time I hear a story like this, “all that is sacred is profaned” runs through my mind.