The Myth Of Cops Overdosing From Touching Fentanyl Persists For A Reason

You should be concerned about the dangers of terrible reporting on drugs from the press.

Discourse Blog has partnered with our friends at Defector to bring you a taste of their work. If you like this piece—which, duh, it’s good—we encourage you to check out Defector and subscribe!

This piece was originally published at Defector on August 12, 2021.

by Dan McQuade for Defector

The pharmacologist listed his credentials for Congress. James C. Munch had his Ph.D. after years of studying toxicology and pharmacology. He had been with the FDA for a decade. He was still a consultant for the Bureau of Biological Survey at the USDA and told the congressmen he had “also been interested in the work of the Narcotics Bureau, particularly in the detection of the doping of racehorses.” He was a professor of physiology and pharmacology at Temple University, and was also in charge of tests and standards for Wyeth, the longtime Philadelphia drugmaker that would later be acquired by Pfizer in 2009.

This was many years before that. Munch testified before Congress about the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, the first federal law that criminalized the possession of cannabis. (Spoiler: It passed.) Munch was one of the expert witnesses. He shared some facts about the drug. That it creates a tolerance in users, that it had some accepted medical uses, and that it was used in some non-medical commercial activities. It was, of course, also consumed recreationally.

He had more, though, which strayed from the known facts. Marijuana could lead to extreme violence—the word “hashish” inspired the word “assassin,” he said. (This is a common myth.) When asked if habitual use of marihuana—the U.S. government spelled marijuana with an “H” until Richard Nixon changed its policy on the drug—“means the disintegration of the personality of the person who uses it,” Munch replied yes. The complete “disintegration” of a personality would not take long, he testified, based on his research on dogs: “Yes, so far as I can tell, not being a dog psychologist, the effects will develop in from three months to a year.”

Munch was not the only one to testify. The American Medical Association actually opposed the bill. Federal Bureau of Narcotics commissioner Harry Anslinger, reading testimony written for him by a district attorney in New Orleans, said: “Marihuana is an addictive drug which produces in its users insanity, criminality, and death.” Without too much debate, marijuana was essentially outlawed federally—a prohibition that continues to this day, though most states now openly flaunt it with laws allowing medicinal and/or recreational use. (Back then, most states already prohibited the drug.)

News coverage of the new law pretty much followed Congress. When it went into effect on October 1, the Associated Press wrote a story that began this way: “Marihuana, the wicked weed that arms cowards with a false and fleeting bravery, came Friday under the severe restriction of the federal narcotic laws.” The story quoted Capt. Roy Ritchburg, head of the Dallas police department’s vice squad. “It makes a coward act for a few hours like the bravest man alive,” he told the AP. “It makes a timid man vicious and cunning. It gives some people hallucinations and a man on a marihuana jag is as likely to attack his brother as he is stranger.” By December 1937, four people were already sentenced to a year-plus in federal prison for violating the Marihuana Tax Act.

I thought of Munch and the furor around violent marijuana users last week when I saw a video posted by the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department. Sheriff Bill Gore, who has been in charge of the office since 2009 and is retiring when his term runs out in 2023, addresses the camera directly. The set is dark. The broader mood is suffused not just with drama, but horror. The sheriff introduces body cam video of what he says is “traumatic” footage.

If you take the video at face value, it is pretty traumatic. The video shows an officer flat on the ground. The video says the patrol deputy, still in training, was processing drugs at the scene of an arrest. He then passed out. A corporal reacts quickly, suspecting an opiate overdose—likely fentanyl, the synthetic opiate that has increasingly taken over the recreational opiate supply. The corporal administers naloxone, also known by the brand name Narcan, which can reverse overdoses. He tells the deputy he’s going to be OK. “I’m not going to let you die,” he repeats. “I’m not going to let you die.” The corporal and the patrol deputy return as talking heads, lit like Sheriff Gore, to recount the story. Eventually, the deputy is wheeled into an ambulance. “He was ODing the whole way to the hospital,” the corporal says. He needed four shots of Narcan up his nostrils to save his life.

The department did not release the full body cam video, and did not release any toxicology reports. When I saw the video last week, I immediately knew that it was not a fentanyl overdose. I volunteer at Prevention Point Philadelphia and I have seen overdoses. I have assisted in reviving people from overdoses. This did not look like that at all. His lips were not blue, for one. The story said the Narcan did not help his symptoms; if he were actually overdosing on fentanyl or another opiate, the shots up the nose would have relieved them. That there was no method of ingestion mentioned—that he was simply overcome by handling fentanyl—was curious. Later, the department clarified he wasn’t even handling the drug; he simply came within six inches of it. To me, it seemed likely the officer had a panic attack.

I also didn’t really need my own experiences to know all of this, because it was not the first time I had seen a story like this. Police officers have been “overdosing” from handling or simply by being near fentanyl for years now. News story after news story detail incidents where cops encounter fentanyl powder, overdose as a result, and are administered Narcan. Fentanyl can be skin-soluble—in specially designed patches that slowly release the drug into the body. This took a lot of work to develop; the drug was synthesized in 1959 and patches were only developed in the 1990s. The story just strains credibility by common sense: Why would anyone inject fentanyl if they could just get high by touching it? Why don’t drug dealers and users ever overdose in this way?

One obvious problem with these stories is that the drug simply does not work in that way. These pseudo-overdoses do not happen to workers at Prevention Point Philadelphia. I’ve been writing about drugs for nearly 20 years; I have held fentanyl in my hands several times and not only have I not overdosed, I’ve felt no effect at all. Inhalation is unlikely, too, as powdered opiates do not aerosolize. New synthetic opiates like carfentanyl behave in this same way; though they are stronger, you can’t overdose them via touch. Police officers—and, sometimes, other first responders—simply believe they can overdose by touching fentanyl, and have a panic attack as a result. Sometimes the officers don’t even pass out and “self-administer” Narcan; this is not impossible, but incredibly improbable for a cop to do.

“Mass psychogenic illness happens all the time,” Jeanmarie Perrone, director of medical toxicology at Penn’s med school, told the Inquirer in 2018. “We see it all the time with law enforcement. Police pull someone over and find an unknown substance. Suddenly their heart’s racing, they’re nauseated and sweaty. They say, ‘I’m sick. I’m gonna pass out.’ That is your normal physiological response to potential danger.” A 2019 study of New York state first responders found 80 percent thought “briefly touching fentanyl could be deadly.” Several news outlets have covered how police are tricking themselves into panic attacks before. Police and other first responders are in no danger of overdose in a situation like this. Cops simply think they are. These stories are so common one doctor, Ryan Marino, shares them with the hashtag #WTFentanyl.

Douglas Hexel is a firefighter in Schenectady, New York. In his spare time, he runs Rescue Med NY. The company trains police departments, firefighters, and EMTs; county cops currently get two weeks of Hexel’s training in the academy. One of his seminars is titled Debunking the Myth of Fentanyl Exposure. He said he’s had success teaching police officers they aren’t in danger of a contact overdose with a simple story. “When I teach this class, and I get to the very end, I still might have some apprehensive people in the room—especially when I’m teaching law enforcement officers,” he said. “I tell them if you know somebody who’s had this happen to them, or you look at any of the videos that I showed you, none of them talked about the really great euphoric high that they get before they overdose.” This makes sense: An opiate overdose may kill you, but it will also get you high first. A cop touching fentanyl and panicking doesn’t get that rush of dopamine one would get before an overdose.

So, it’s pretty clear the video does not depict an opiate overdose. That did not stop the incident from spreading across the Internet. People shared the video. Though many users on Twitter ratioed the tweet and pointed out that the sheriff department’s recreation of the incident was impossible, it still went viral as a cautionary tale. Cops shared it. The Clay County (Missouri) sheriff’s office shared it with a similar myth about fentanyl-laced weed. And since the San Diego sheriff’s office had been generous enough to produce this slick, dramatic, traumatic video for the press, the press went ahead and shared it.

The San Diego Union-Tribune wrote an article about it that only quoted cops. The Los Angeles Times syndicated that story. CNN reported the tale. As did ABC. The New York Daily News did, too. Stars and Stripes had a report. So did, for some reason, Mediaite. Thanks to syndicated content from San Diego, local news stations around the country carried some report: Los Angeles; San Francisco; Dallas; Corpus Christi, Texas; Butte, Montana; Dayton, Ohio; West Michigan; Southern Colorado. Here in Philadelphia, 6 ABC ran it on their website and on the news at 4:00 p.m. and 5:00 p.m. on Friday. Even a hip-hop website called My Mixtapez covered it. (DatPiff did not.)

More reports, ones that quoted more than just police officers, came a few days later. The New York Times headlined its story about it “Video of Officer’s Collapse After Handling Powder Draws Skepticism.” NBC News’ report was “Viral video on San Diego deputy’s fentanyl exposure raises questions.” “You can’t just touch fentanyl and overdose,” Marino, the #WTFentanyl doc, told NBC News. “It doesn’t just get into the air and make people overdose.” Leo Beletsky, a Temple law graduate with a masters in public health, told the Times “it is not biologically possible” to overdose on fentanyl from touching or being exposed to the drug. (He’s much more of a credit to the institution than Dr. Munch.) Still, despite the outlets’ reporting and citations from the National Judicial Opioid Task Force and a peer-reviewed research from the International Journal of Drug Policy, the cops aren’t said to be lying in cases like this, or even wrong. They simply have raised questions and drawn skepticism. The San Diego sheriff didn’t even comment, telling the Times that both the corporal and trainee deputy were on vacation. (A trainee already gets vacation! This is why you should organize with your coworkers, friends.)

Let’s go back to the 1930s and Dr. Jimmy Munch and his public campaign against the dangers of marijuana (or “marihuana”). When his Congressional testimony was through, he just kept talking. The following year, Munch was called as an expert witness in a homicide trial—for the defense. Ethel Strouse Sohl, a 20-year-old policeman’s daughter, and Genevieve Owens, 18, had shot and killed a bus driver when attempting to rob him of $2.10. Thirty-four-year-old William Barhorst was killed. It was a senseless crime, but Sohl had a unique defense: She couldn’t be held responsible for what she did, as she was under the influence of marihuana.

She said she was driven to withdraw $100 from her friend’s bank account after smoking weed. The drug, she testified, also drove her to take her mother’s car, grab two guns (one her father’s, the other belonging to her codefendant’s father) and begin a robbery spree. She needed more money for weed, and simply could not help herself. The drug “made wrong things seem right.”

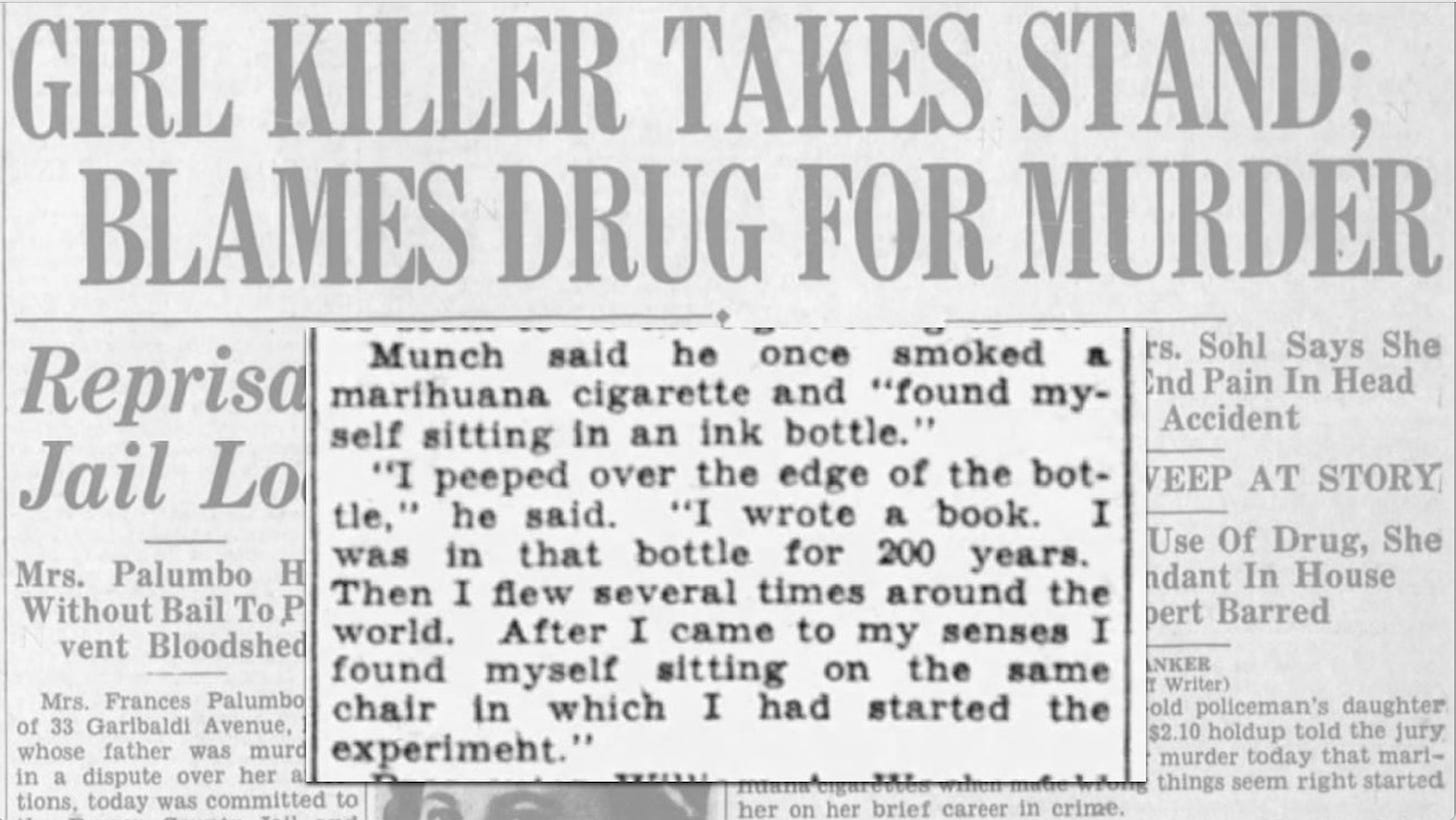

Munch was not allowed to introduce his evidence about the dogs—presumably the defense couldn’t find a dog psychologist—but he was able to testify. Identifying himself as a drug expert for the League of Nations, he said he’d taken the drug himself and it produced “bizarre, gruesome effects.” According to a speech the noted law professor Charles Whitebread gave in 1995, Munch expanded on these effects: “After two puffs on a marijuana cigarette,” Munch said, “I was turned into a bat.” He added that smoking marijuana led him to believe he had “been in an ink bottle for 200 years.” (Note to self: Ask weed dealer about this “Ink Bottle” strain.)

Sohl and Owens were found guilty. But some in law enforcement considered the defense a success, as they were sentenced to life imprisonment and not the death penalty. Newspapers printed Munch’s tales, reporting that weed had turned a doctor into a bat. More weed-related defenses followed. In his speech, Whitebread shared one where being near marijuana caused “homicidal vibrations.”

Anslinger, the head of the narcotics bureau, eventually told Munch to knock it off—and he did, returning to his previous research on the doping of racehorses, having horse saliva samples brought to his Upper Darby laboratory to test them for morphine doping. (A speech he gave about “modern horse thieves” in 1944 was spotlighted in a newspaper with the headline “Get Them Thar Hoss Thieves.”)

Munch’s testimony on marijuana sounds silly to us now—and probably did at the time to weed users as well. But it continued to influence the news media decades after he gave it. In 1970, syndicated columnist Ray Cromley wrote a story about marijuana. “One of the cruelest campaigns ever conducted in this country,” he wrote, “has been directed at convincing marijuana is no serious danger—‘no worse than alcohol.’” He cited Munch, saying marijuana leads to “progressive brain damage and death from cardiac failure.” He did not mention how marijuana can turn you into a bat. (Note to self: Maybe the strain Batman OG does that? Make sure to test.)

The idea that marijuana made users homicidal and led to progressive brain damage persisted among those in the drug-fighting business, despite much evidence to the contrary, and that lurid and unscientific paranoia very much applies to other drugs. This myth of close-contract fentanyl overdoses seems to have started in June 2016, when the Drug Enforcement Administration under Barack Obama released a video made in consort with detectives in Atlantic County, New Jersey. It told a story of two police officers who overdosed while handling suspected fentanyl. “A very small amount ingested, or absorbed through your skin, can kill you,” then-acting DEA deputy Jack Riley said. The bulletin added: “Just touching fentanyl or accidentally inhaling the substance during enforcement activity or field testing the substance can result in absorption through the skin.” And just think of the poor doggies! “Canine units are particularly at risk of immediate death from inhaling fentanyl,” the video claimed. Hexel, the firefighter and teacher, told me that this has never happened.

The story spread. Though Donald Trump’s DEA released new guidelines in 2018—“One myth is that just touching any amount of fentanyl is likely to cause severe illness or injury or even death and that’s just not true,” a video said—it didn’t matter. That International Journal of Drug Policy report found no confirmed cases of fentanyl overdoses through the skin. Cops still believe it, though; a study in June in the Harm Reduction Journal found that “nearly all leaders and officers interviewed wrongly believed that dermal exposure to fentanyl was deadly.”

On this particular story, the press has corrected itself a bit. The Associated Press now has a report questioning the video and that has also been syndicated across the country. But that doesn’t seem to matter. Another study, also from Beletsky and friends, found that corrective stories weren’t shared nearly as widely as the overheated and dishonest ones that showed officers allegedly overdosing.

As with Munch’s testimony, there are consequences to this regardless of how obviously stupid and false it is on its face. The same day the San Diego video was released, the Douglas County (Colorado) Sheriff’s Office sent it to all its officers as a “training video.” Sheriff Tony Spurlock told the media: “It can easily happen to any officer on any day on any street.” At the risk of repeating myself, it absolutely can’t, but now Spurlock’s officers believe it can.

That was evident just this past weekend in California, where the San Diego video spread most widely. A police officer in Anaheim was transporting a suspect on drug charges and began to feel lightheaded. He ended up being OK; he was not administered naloxone and didn’t go to the hospital. He did not overdose. The headline in the Orange County Register: “Anaheim officer treated after possible fentanyl exposure.” Another similar case happened in Clovis; two cops were treated for suspected fentanyl exposure after handling a plastic container with suspected fentanyl in it. Both were reported by the press as fact; both seem to be just cops seeing the San Diego story and panicking.

People have gone to prison because of this myth. In 2018, a man in Ohio pleaded guilty to assault on a peace officer after an officer touched fentanyl powder on his shirt. That man was sentenced to six years in prison on the “assault” and drug charges; the officer, Christopher Green, was fired in June for more than two dozen violations of the policy manual, including dishonesty, discourteous treatment of the public and gross misconduct. (He denies the allegations.)

And it’s not just cops who believe this. Users on Twitter debunking the San Diego video got plenty of replies from others who just refused to believe them. One of them was Hal Sparks, the old host of Talk Soup between John Henson and Aisha Tyler. He got into a long argument with Marino and another user about how “packages, bags and cloth surfaces that police handle often PUFF the drug in the air” and that is how police overdose. “Get back to me when you give a real shit about real people,” he tweeted to people correcting the story.

And this belief leads to danger from drug users themselves. They will, no doubt, be knowledgeable enough about the drug to know they can’t get a contact overdose. But if users overdose, someone—a cop, a paramedic, a firefighter, or just a bystander—might not want to help because they are scared of overdosing themselves. This myth is most pernicious around cops, and in many places in the country police are the first ones to arrive to any 911 call.

“There’s a lot of places in this country still, where you call 911—say, because you’re having a heart attack—and the first person who shows up is the police officer, because places have volunteer fire departments and volunteer ambulances,” Hexel told me. “Even if it’s a medical emergency or a fire, the first person who’s going to get there is a police officer, because there’s millions of people across the country, where the only paid service that they have are the police. Most police now carry Narcan. And if we’re giving them Narcan, but they’re thinking in the back of their head, ‘If I get too close, this can happen to me,’ they’re going to be less apt to help and they might just try to stay back…. More people are going to die.”

Reversing this belief in overdoses-by-touch is possible. Though there is now an open letter from drug professionals and others calling on news outlets to stop repeating this falsehood, I think the change is going to have to come from police officers and other first responders. Classes like Debunking the Myth of Fentanyl Exposure have convinced his students; they no longer have this needless fear. Other instructors have worked, too. A study in Harm Reduction Journal a year ago held 11 trainings for around 200 cops and paramedics. Those classes began with about 20 percent of EMTs and cops knowing you can’t overdose due to brief contact with fentanyl or other opiates. They ended with more than 80 percent believing the truth.

And changing police minds is almost certainly going to have to be the answer, because in general media outlets have not cared enough about being accurate about drug reporting. They just follow the cops. In America, drugs besides alcohol are covered as a moral issue. Cops are quoted. Maybe doctors and health professionals are quoted. But rarely do reporters talk to drug users—the ones who know the most about drugs. Drugs besides alcohol—and, increasingly, marijuana, which must have Dr. Munch spinning in his grave—are viewed as bad, and their users are viewed as bad. But most drug use, even of opiates, is non-problematic. Despite this, drug users often aren’t viewed as people—they’re viewed as lost souls ready to be saved. They are just background noise, even in stories about drug users.

Here’s an example. Recently, Atlantic City voted to shut down Oasis, its needle exchange and services center. Many news outlets covered this. The Philadelphia Inquirer, The Press of Atlantic City, WHYY-FM, NJ.com, Buzzfeed and Politico all wrote stories. Some of these were quite good: They carefully explained why a needle exchange is helpful in preventing the spread of HIV, hepatitis and other diseases; they shared powerful stories about former exchange users getting into treatment with Oasis’ help; they even showed that those who wanted to shut down the exchange in Atlantic City had some bit of a point (there should be more than one place to get clean needles in Atlantic County). They were, by common journalistic standards, pretty good. But only one reporter, the Press of AC’s Molly Shelly, quoted a current user of the exchange. Even The New York Times story on the subject this week quoted an exchange user who is sober four days and was getting needles just in case.

Politico’s story, by Sam Sutton, was a good example of how the press treats drug users in general. It doesn’t talk to any of the exchange’s users, but it does describe a person near the exchange: “In front of a small brick building on a littered stretch of South Tennessee Avenue, a thin man is hunched over — pants around his ankles — picking at the sores on his legs.” That’s the first sentence of the story, and it paints heroin users in a very negative light. A needle exchange’s clientele varies. But the press is in lockstep with the police in its depiction of drug use: All of it is bad, and all of it is should be wiped out. The press might as well be a McGruff album from the 1980s calling users “losers.”

It’s nice that NBC did a story debunking the San Diego video. But its website still has, for example, a story about a police officer overdosing after brushing powder off his uniform active on its website. “Drugs dealers typically lace heroin with fentanyl — the drug that killed Prince — to boost profits and to give the drugs more punch, often with fatal results,” that story ends.

The Miami Herald ran a story about police panic attacks last year; it did not stop its website from also running a breathless story about the San Diego video. Both stories were syndicated by McClatchy News Service. Upper-level police are doing a bad job teaching their officers about fentanyl. So are upper-level media members! So you get situations where McClatchy’s science reporter debunks a police falsehood but a real-time McClatchy reporter based in Washington state didn’t get the memo and repeats the cops’ story. Most outlets have not corrected their stories; some have changed the syndicated headline from “It’s an invisible killer” to “Video of San Diego deputy’s near-fatal fentanyl overdose raises questions about how it could happen” but the story remains the same.

And even the corrections on this story seem to be more about covering things up than correcting the record. Last. month, Los Angeles Times “courts and cops” reporter James Queally scoffed at the idea his paper was full of “LAPD stenographers.” First, the original Times story remains up, with paragraphs that completely undercut the premise of the story added near the end. Second, here’s how the paper’s mea culpa on the San Diego video coverage, written by metro reporter Maria La Ganga, begins:

A public service video from the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department about the dangers of fentanyl — with footage of a deputy allegedly overdosing after brief exposure — has sparked a backlash and allegations that the anti-drug effort could harm the very people it’s meant to help: law enforcement officers and drug users.

Yeah, OK. This is police stenography. The video was not meant to help drug users. They know that fentanyl does not work this way. Cops care about arresting drug users and punishing them. The video was meant, primarily, to get the San Diego sheriff some positive attention. This worked, but only briefly. But that positive attention leads to a lot of places: It advocates for more funding for police and the drug war. It shames drug users and sellers, pretending their product is a hypothetical poison from a spy movie. It attempts to help keep cops out of prison; that George Floyd had taken fentanyl before he was killed by Derek Chauvin was part of the defense in the trial.

Mainstream coverage of drugs in the U.S. primarily comes from police officers. Drug busts get big coverage. Cops are quoted with nonsensical statements like “the amount of fentanyl seized in this single operation enough lethal overdoses to wipe out San Francisco’s population four times over.” News outlets do breathless stories about “new” drug formulations. Drugs are, for the press, a moral issue. The press generally believes using drugs besides alcohol is wrong, and reacts accordingly. Doctors and other medical professionals the press quotes are generally on the same wavelength. They share information that is true—fentanyl can be incredibly dangerous, marijuana users develop tolerance—and tack on a little more when they feel it’s necessary. In general, a lot of people don’t even care when someone lies about the danger of drugs: In fact, exaggerating may be a good idea, with the idea that if it stops just one kid from trying drugs, it’s worth it.

I don’t believe that drug use is wrong. Your morals may vary. But I do think you should be concerned about the dangers of terrible reporting on the subject from the press. It leads to bad outcomes for drug users and non-drug users alike. Current reporting isn’t much different than when the press reported on Dr. Munch and his ink bottle. Reporting on fentanyl in 2021 may not be as obviously wrong as the tale of his 1937 transformation into a bat, but it’s still wrong.