The Most Important Senate Primary of 2020 Is Happening Today

Can a Bernie-style candidate win in the headquarters of Corporate America?

Politicians in Delaware pride themselves on the Delaware Way, a longstanding principle that, since the state is so small, you can get everyone in a room together and hash out almost any problem. That’s never been the case, but it has fostered an almost obsessive tendency toward bipartisanship and civility. It has also meant that primary challenges to incumbents are generally viewed as not just a typical challenge to power but as something akin to bad manners.

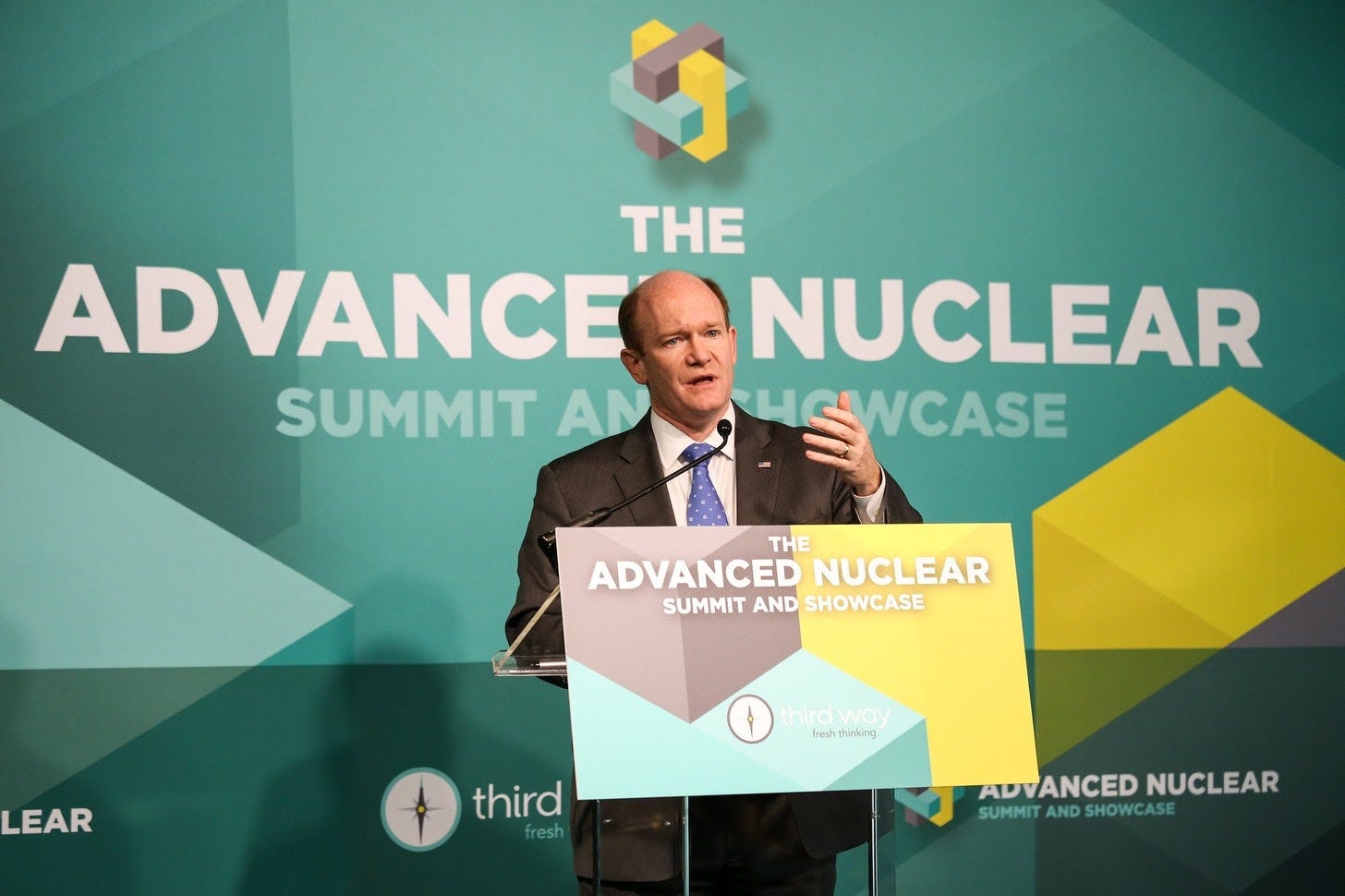

The last decade has completely upended these norms, and 2020 is the boiling point. There are competitive races up and down the ballot in the final state to hold a primary election in 2020. At the very top of the list is Delaware’s Democratic U.S. Senate primary between incumbent Sen. Chris Coons and Wilmington activist Jess Scarane.

Coons and Scarane represent two very different strains in the Democratic Party. Like his predecessor and close ally Joe Biden, and his fellow Delaware senator Tom Carper, Coons has taken the way things are done in Delaware with him to Washington and built a reputation for himself as a pro-business “bridge-builder” between the Democrats and the GOP; Politico once dubbed him “the GOP’s favorite Democrat.”

But as popular as he is with Republicans, Coons is markedly less so with the left wing of his own party, due to his vocal criticism of progressives and their policy demands.

Scarane is essentially everything that Coons isn’t. A 35-year-old former nonprofit board president who works in digital marketing, she is running on an agenda familiar to anyone who has followed the recent post-Bernie Sanders wave of insurgent leftist campaigns: support for Medicare for All and the Green New Deal, opposition to endless war and Wall Street giveaways, and a clean break from the civility politics that have defined Coons’ near-decade in the Senate.

“There are so many things causing struggle in our country, and we can’t continue to accept the status quo,” Scarane told Discourse Blog in a phone call earlier this month. “My entire lifetime we’ve only had leaders nibbling around the edges, and that’s led to a government failing to support its people.”

But though this primary will see the lower end of 100,000 voters at most, and Coons is the clear favorite to win, the importance of the race can’t be overstated—not just for Delaware, but for the project of the electoral left across the country. More than any other race in recent memory, the race in Delaware is a referendum on corporate power and the influence of business in a state where fewer than a million people live but more than 1.5 million business entities are incorporated, and where more than two-thirds of all Fortune 500 companies are incorporated but nearly one out of every six children live in poverty.

Scarane’s run also represents a clear, potentially effective model for building a left power base in the Senate: small states that lean Democratic and have a population barely larger than a congressional district, which requires fewer resources spent on trying to reach people and build name recognition.

“I hear Delaware is a centrist state. It’s untrue. Maybe the representation we have [is centrist], but people recognize the country can be better, and they’re for that,” Scarane said. “We have to realize people who aren’t mainlining politics online all day aren’t using the exact same words, but they understand the concepts we’re fighting for.”

Ten years ago, Chris Coons was a sacrificial lamb-to-be.

When Joe Biden was elected vice president in 2008, he was also re-elected to another term in the Senate—it would have been his seventh—by walloping a then-unknown Republican activist named Christine O’Donnell. Biden resigned his Senate seat, which triggered a special election, to be held in 2010. In the interim, Biden was replaced by longtime aide Ted Kaufman, who immediately announced he wouldn’t run in the special election.

Longtime U.S. Rep. Mike Castle, a Republican, was the last conservative stalwart in a place that had been slowly and methodically taken over by Third Way Democrats. Though the Democrats hadn’t lost a presidential election in Delaware since 1988 or a U.S. Senate race since 1994, Castle, a former governor, cleared the Democratic field of any major names, including Biden’s eldest son, Beau, then the state attorney general.

Coons, the then-New Castle County executive, thus ran unopposed in the 2010 primary in a fairly no-risk, high-reward proposition. Even if he lost, he would increase his statewide name recognition after taking one for the team, and his consolation prize would still be running Delaware’s largest county.

But then O’Donnell came back around, and in the Tea Party wave of 2010, she narrowly defeated Castle. Whereas Coons was widely expected to lose to Castle, he became a frontrunner overnight against O’Donnell and ended up beating her by double-digits. He was then easily re-elected in 2014.

In the Senate, Coons has attempted to replicate Biden’s approach of building rapport with the moderate and even conservative wings of the GOP. Coons came to national prominence as a result of these relationships, most notably his one with Sen. Jeff Flake when he helped convince Flake to vote to launch an FBI investigation into sexual assault allegations against Brett Kavanaugh in 2018.

The effort did not stop Kavanaugh from being confirmed to the Supreme Court, and Scarane told Discourse Blog that the episode—which she said allowed Flake "cover" to ultimately vote for Kavanaugh—was emblematic of the problems with Coons' method.

“He champions bipartisanship without saying what that bipartisanship gets us. It’s that focus on compromise and getting something done without focusing on what it gets done for the people of Delaware,” she said. The Coons campaign didn’t respond to a request for comment sent on Sunday.

Coons, who as a student worked for Delaware Republican candidates before becoming a self-described “bearded Marxist” following an undergraduate trip to Kenya, has also drawn ire from progressives over his stances on war, healthcare, and particularly his friendliness toward Trump-nominated judges.

In 2019, Coons voted to confirm 45 Trump nominees to the federal bench, including some who didn’t explicitly affirm the landmark education ruling Brown vs. Board of Education. The liberal group Demand Justice, which focuses on the courts, launched a five-figure Delaware ad buy last year attacking Coons for voting for the latter. Coons’ fellow Senate Democrats rushed to defend him; Sen. Dick Durbin of Illinois called it “way out of line.”

Beyond policy, Coons has further infuriated the left with his attitude towards the current political moment. At various points, he has scolded progressives for being too “wild-eyed,” has slammed fellow Democrats for chanting “lock [Trump] up,” and compared the left to O’Donnell for its “purity-driven exercises” like demanding that candidates support single-payer healthcare and not participate in Mitch McConnell’s scheme to pack the courts with right-wingers for the next forty years.

In April 2017, when Democratic opposition to Trump was as fierce as it's ever been, Coons chose to join up with Susan Collins in circulating a letter to fellow Senators pledging to “preserve existing rules, practices, and traditions” of the United States Senate.

(Coons has since changed his tune, kind of; in an interview with Politico earlier this year, he indicated that the Senate might have to kill the filibuster if the GOP tries to obstruct a Biden presidency.)

While Coons’ approach has pissed off progressives, it has only endeared him to the GOP and like-minded Democrats. It’s an undeniable dynamic in the Senate: there are a lot more people like Chris Coons then there are like Jess Scarane. And Coons’ roots in Delaware politics are good preparation for the Senate, which prioritizes cooperation, is aggressively anti-conflict, and thumbs its nose at democracy almost by nature.

But considering the Senate isn’t going to be abolished anytime soon, Scarane thinks the way for the left to build power in a legislative body as reactionary as the Senate is to target a handful of small states like hers. The entire state has 348,007 registered Democrats, according to the office of the State Election Commissioner, and the 2018 Democratic Senate primary had just 83,000 votes total, fewer than some congressional primaries in New York this year. As of last week, more than 100,000 absentee ballots had been requested in the state and 56,000 had been returned, according to Delaware Public Media.

And so even if Scarane loses, her run shows a path forward for the left in Senate and other statewide races: small states with at most 300,000 or 400,000 Democratic primary voters and a practically nonexistent Republican Party, places where Democrats can’t credibly make the argument that nominating a progressive will give away a seat to the GOP.

Coons is not particularly vulnerable. He doesn’t have corruption issues like Bob Menendez in New Jersey, and while Coons is consistently critical of the left and a huge obstacle to the party moving left, he’s not so conservative as to be out of lockstep with mainstream Democrats, like Illinois Rep. Dan Lipinski was when Marie Newman beat him earlier this year.

But Coons isn’t a giant of state politics on the level of Biden or particularly Carper, a four-term senator and former governor who fought off his own primary challenge two years ago. A strong Scarane performance could spur questions about Coons’ popularity in Delaware and whether or not he was just at the right place at the right time in 2010. (A big Coons win could also solidify his position as the leader of a new generation of Delaware centrists.)

Beyond Delaware, the left should take some inspiration from Scarane. With some money and committed volunteers, left-leaning candidates could feasibly mount strong campaigns for a slew of Senate seats in the coming years, in places like New Jersey, Rhode Island, Vermont, Connecticut, and so on. Last week in Rhode Island, for example, 15 candidates endorsed by progressive groups like Reclaim Rhode Island and the Working Families Party won their primaries, including against the president pro tempore of the state Senate; at the same time, longtime U.S. Sen. Jack Reed was unopposed in his primary, where he received fewer than 33,000 votes as the only person on the ballot.

“If we care about building progressive and left power, we have to put our power in states where we can win. It’s the size of a congressional district,” she said of Delaware’s voting population. “And it's the effort we would put into a congressional district, for six years.”

Scarane said she decided to run for office after serving as the president of the board of the Delaware chapter of the nonprofit Girls Inc, which aims to support young women and girls, and becoming frustrated at the lack of resources for poor and working-class people from long-ignored neighborhoods. “That work was powerful and inspiring, but it doesn’t solve the root causes of those issues,” she said. “These are federal issues.”

She said her politics have also been influenced by her own encounters in the workplace. “I talk about my experiences in the workplace, starting work at 14 and experiencing sexual assault and harassment, being underpaid, being marginalized, being made to feel completely expendable, and being told my opinion doesn’t matter because someone behind me would take my job,” Scarane said. “It took me getting power in the workplace to realize that [dynamic] was at play all along. Our system treats people as expendable and churns through them.”

Simply put, Scarane is anathema to the kind of politics that most Delawareans are familiar with, a genuine leftist in a state that’s still as relentlessly corporate as it was when Ralph Nader published “The Company State” almost fifty years ago. Carper was a model Third Way governor in the 1990s, and as a senator, Biden was derisively referred to as “the Senator from MBNA” due to his ties to the financial sector. (Full disclosure: I interned for both Carper and the state Democratic Party in college.)

Due in large part to the GOP’s rightward shift and the Democrats' friendly ties to business, Delaware Democrats have, like their counterparts in other formerly Republican-dominated states in the mid-Atlantic and Northeast, fully taken over every aspect of Delaware’s government. The Democrats control all of the state’s executive offices, both chambers of the state legislature, both U.S. Senate seats, and its one House seat. Within the party itself, moderates like Coons dominate.

But the last few years have started to change that. In 2018, veteran and community organizer Kerri Evelyn Harris launched a run against Carper for Senate. It was slow to get off the ground, but after Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez defeated Joe Crowley in New York, Harris’ campaign briefly became the next battle in the long, ongoing fight between the left and centrist wings of the Democratic Party.

Harris ultimately pulled 35 percent of the vote, a remarkably strong outing considering Carper’s popularity and the fact that he spent ten times as much on the race as Harris.

Scarane is at an even bigger disadvantage moneywise. Since announcing her run for Senate last November, she’s raised nearly $324,000 and spent almost $175,000 as of the latest FEC filings, a respectable amount. But since the beginning of 2019 alone, Coons has raised nearly $5 million for his re-election bid and spent more than $2.7 million—fifteen times as much as Scarane. (Plenty of Coons’ money has come from corporate PACs, as Sludge has recently reported; Scarane has pledged not to take corporate PAC money.)

But last year, a survey run by Data for Progress showed a hypothetical “more liberal female Democrat” outpolling Coons and wide support for the policy proposals adopted by Scarane like Medicare for All and the Green New Deal. (Scarane announced her run last November, while the polling was ongoing; there has been no public polling in the primary race since then.) While Scarane admits the pandemic has complicated her efforts to build name recognition, she told Discourse Blog that her campaign and its volunteers have made over 600,000 calls since the beginning of the primary, she’s run digital and television ads, and she’s held Facebook Live Q+As and “DIY debates” since Coons—unlike Carper in 2018—refused to debate her.

She still has an uphill battle, though. In addition to the financial disadvantage, Coons is genuinely well-liked in Delaware: a Morning Consult poll earlier this year found he was the ninth-most popular senator among his constituents, with a 52 percent approval rating. Scarane credits Coons’ popularity to the perception among Delawareans that Coons is a nice guy but dismisses that as “aesthetics” and people not really knowing his record. Coons also has the backing of virtually the entire Democratic and Delaware establishment. Even NARAL, the pro-choice group, endorsed him earlier this month over Scarane, a progressive feminist.

While Delaware Democratic Party executive director Jesse Chadderdon told Discourse Blog that the party’s resources are focused on the general election, the party executive committee voted to endorse Coons. Scarane tweeted a Delaware Democratic Party mailer over the weekend that included Coons on its slate of candidates and questioned how “agnostic” the party really is in the race.

“What has been communicated to candidates—and what is true—is that all of the Party’s direct voter contact and organizing efforts are candidate agnostic,” Chadderdon said. “But a party shouldn’t be expected to muzzle itself from publicizing its own endorsements—and that’s true whether we’re talking about the Democratic Party or the Working Families Party.” (The Working Families Party had spent $50,000 on independent expenditures supporting Scarane’s campaign as of last week, according to Open Secrets.)

While the Scarane-Coons primary is the most nationally prominent of all the races in Delaware on Tuesday, Chadderdon said he thinks down-ballot primaries have taken up more attention from Democratic activists and voters this year and questioned the desire of Delaware Democrats to dump Coons.

“People like Chris Coons are really popular in Delaware. We have a lot of progressives in Delaware who are voting for Chris,” he said. “I think Chris has some progressive bonafides and he’s seen as someone who governs the right way. So I’m not sure there’s this clamoring to unseat him outside of the activist base.”

But Chadderdon acknowledged that progressives are gaining influence within the party, specifically naming Harris as someone who “does a wonderful job being a bridge-builder and whose differences are communicated professionally and above board.”

“We try very hard to make it clear there's room in this party for everyone, and we try to live those values by standing up for our platform and making our process very democratic,” he said.

Whatever the result, Scarane’s campaign and the other down-ballot races on Tuesday indicate that the long-dormant Delaware left is finally making some noise. It remains to be seen, though, whether they can turn that frustration into power.

“I think that it’s crucial to fight to get more people who are focused on getting more working-class people elected. It’s a very large platform when you have a Senate seat to drive action out of people, to harness people’s energy and direct it and using that power to shift how people think about Delaware,” Scarane said.

“We’re already doing that with our campaign,” she added. “We need to start changing who holds power in our state.”

Photo courtesy of the Jess Scarane campaign

I have a lot of appreciation for this article because I have seen so little coverage of small-state politics this year, particularly on the left, and this was so informative. Looking forward to more pieces like this from you and Discourse Blog!

Why is Scarane Bernie-style and not (or maybe she is) more AOC-style? I understand there are policy similarities with Bernie but those are there with AOC as well. Scarane seems more comparable to AOC given she's a younger political newcomer.