The Lost Art of Ukrainian Painter Maria Prymachenko

The Russian invasion destroyed the work of the folk artist. The reaction shed light on the art and culture we think is worth saving.

In the last few years, much attention has been paid to the fact that it’s both categorically impossible and deeply harmful on many levels to try to care about every single thing that’s happening in the world. Trying to hold each of this planet’s catastrophes in one’s mind at every moment, ingest all there is to ingest about them, process those things critically, and feel feelings about those things without having a meltdown?? Yes, fully impossible. Of course, it’s a privilege to be able to compartmentalize, but it’s also a necessary shield for survival and for storing energy to keep up the fight.

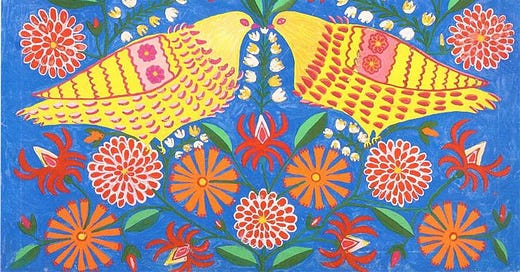

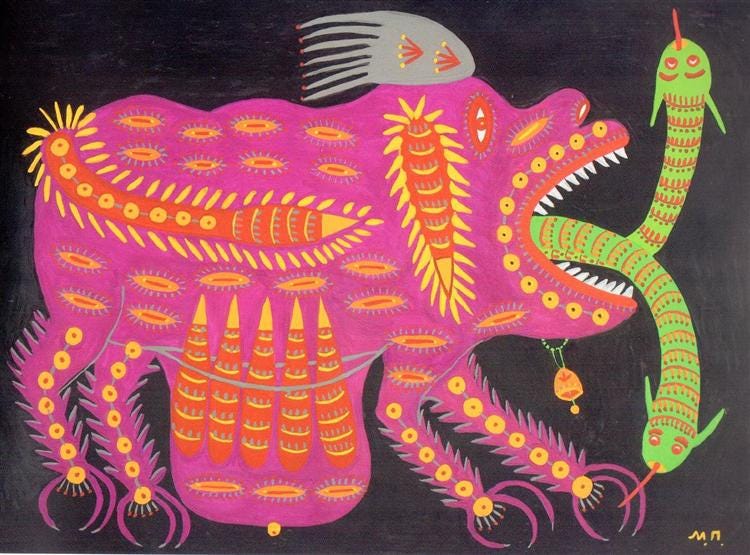

I thought about all of this a lot last week when I developed a full-blown obsession with Maria Prymachenko, a Ukrainian folk painter who died in 1997, and about 25 of whose works were destroyed when the Ivankiv Historical and Local History Museum burned to the ground on February 27.

Here is the announcement from Ukraine’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs:

As referenced in the tweet, Pablo Picasso was among Prymachenko’s fans and after seeing her work, he reportedly said, “I bow down before the artistic miracle of this brilliant Ukrainian.”

When the news broke, I was stunned to have never heard of Prymachenko. Her art is bright, bold, moving, poetic, and feels like the kind of art that is more compulsion than construction. I pored over her works, read about her life, mourned, and felt an acute awareness that this obsession was, in many ways, a means of trying to work through my grief over the Russian invasion, my present fears for Discourse Blog’s own Jack Crosbie (who is now, thankfully, out of harm’s way), and my sorrow for the state of the world in general.

Prymachenko’s work has a timelessness to it—I could 100 percent imagine it appearing on the Instagram account of a contemporary artist today—and ranges from the sweet (This Bear Wants to Have Some Flour Milled), silly (A Coward Went A-Hunting), and fantastical (This Beast is Making Magic), to pieces that are grounded in home (May I Give This Ukrainian Bread to All People in This Big Wide World), self-reflection (Years of My Youth, Come Visit Me) and even war (Our Army, Our Protectors). I became especially engrossed with this piece, titled May That Nuclear War Be Cursed!

As my obsession with Prymachenko grew, it started to intertwine with passages I’d recently read in Susan Orlean’s The Library Book. The book is a sprawling love letter to libraries interwoven with a hunt to find the truth about the source of the devastating Los Angeles Central Library fire of 1986 that destroyed 400,000 books. (If that sounds at all interesting to you, I really recommend it!) At several points, The Library Book contains vivid descriptions of what happens to a volume when it’s on fire—a surprisingly triggering thing even within a book that’s explicitly about a library fire. She spends one section in particular on coordinated book burnings in history, largely in the context of war, which includes this passage:

“War is the greatest slayer of libraries. Some of the loss is incidental. Because libraries are usually in the center of cities, they are often damaged when cities are attacked. Other times, though, libraries are specific targets. World War II destroyed more books and libraries than any event in human history. The Nazis alone destroyed an estimated hundred million books during their twelve years in power. Book burning was, as author George Orwell remarked, ‘the most characteristic [Nazi] activity.’”

And a bit later on:

“In Poland, eighty percent of all books in the country were destroyed. In Kiev, German soldiers paved the streets with reference books from the city's library to provide footing for their armored vehicles in the mud. The troops then set the city's libraries on fire, burning four million books. As they made their way across Russia, the troops burned an estimated ninety-six million more.”

Orlean chronicles many other atrocities against literary culture throughout history and I frankly cried big sobs while reading it, even before Russia invaded Ukraine, before these issues were fresh and real and present, and before I knew the name Maria Prymachenko. By the time I got to the line, “Destroying a culture’s books is sentencing it to something worse than death: It is sentencing it to seem as if it never lived,” I had to put the book down.

My fixation on Prymachenko was straightforward in one sense: her artwork absolutely rules and the loss of her pieces and the Ivankiv Museum as a whole was devastating. In another sense, it was a channel through which to process the horror of the current war. In a third, it was a channel through which to process all the culture lost, ruined, or stolen because of war, occupation, colonialism, and genocide.

It’s not lost on me that I cannot recall seeing so much coverage focused on a single artist amid the countless art, books, and artifacts destroyed in conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and other countries during the last few decades. It’s a product of racist media coverage and undoubtedly my own negligence, and it’s hard not to mourn all over again knowing that many of these precious works aren’t even getting a funeral. They’ve been lost and ignored by the wider world, further burying them and their place in our collective cultural story.

So much has been made of art that was destroyed in World War II, but the obsession doesn’t seem to translate to contemporary losses in say, the Middle East and Africa. That’s especially “weird” (spoiler: not really!) in light of the fact that, following the devastation of World War II, the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict was specifically organized as a response to prevent such losses from happening again. Signing the agreement makes it illegal for a signatory to target another country’s cultural property, so like, if say the president of the United States were to tweet…

"Let this serve as a WARNING that if Iran strikes any Americans, or American assets, we have.........targeted 52 Iranian sites (representing the 52 American hostages taken by Iran many years ago), some at a very high level & important to Iran & the Iranian culture, and those targets, and Iran itself, WILL BE HIT VERY FAST AND VERY HARD”

…and then follow through with that, it would be against the law.

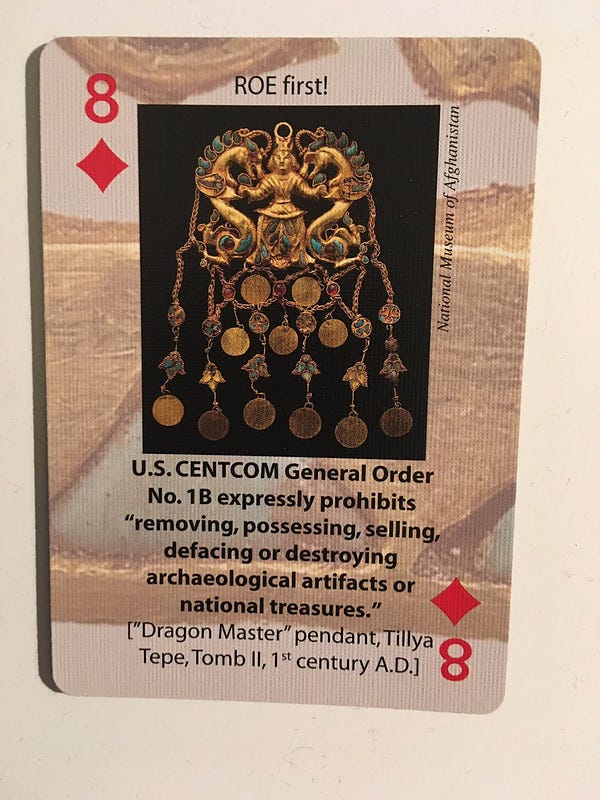

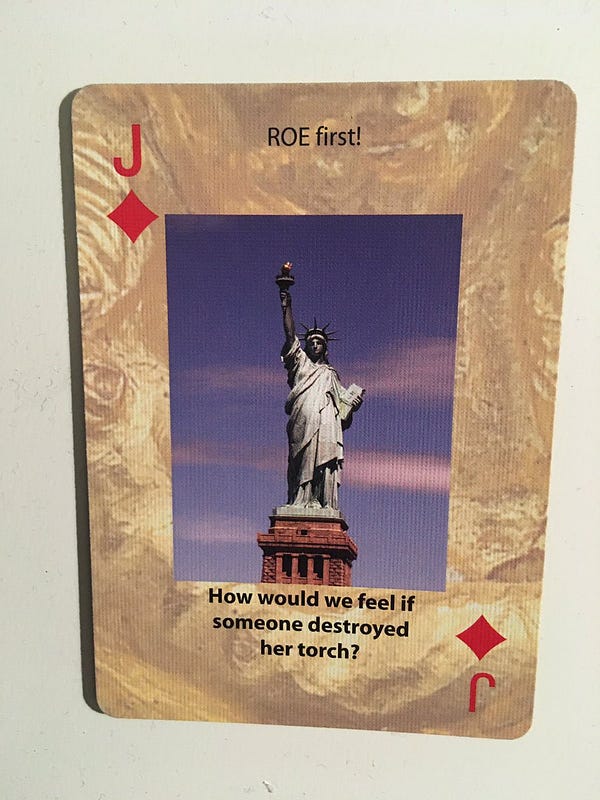

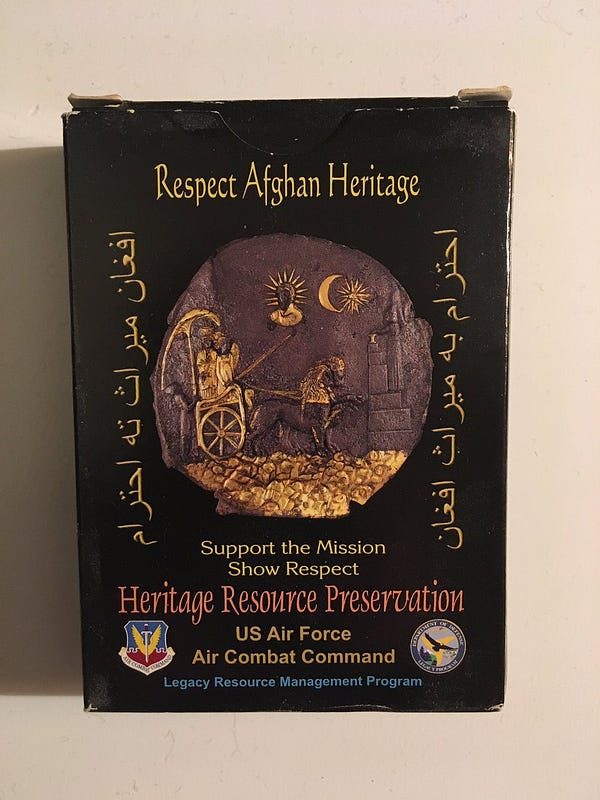

The United States didn’t actually ratify the convention until 2009, but it signed back in 1954, and the concept has been part of official U.S. military policy since even before then, extending to the modern era in which American troops were given packs of playing cards to identify culturally significant sites in Iraq and Afghanistan:

Naturally, the show of good faith—and your mileage may vary on how much you want to believe in the capacity of the U.S. military to exhibit such a thing—doesn’t really matter now and it never really did. Thousands of Iraqi artifacts were stolen in the 2003 U.S. invasion. Russia is currently leveling museums in Ukraine (for what it’s worth, both countries have signed the 1954 Hague Convention). In the face of modern warfare and the hyper-militarization of the world, such protections are negligible. The media coverage and the history books are racist, and the shows of diplomacy are often a sham.

The loss of cultural works isn’t the most important or immediate horror of war—that is and will always be human lives. But the catastrophic consequences of the destruction of culture is impossible to overstate. At the moment, the race is on to preserve Ukrainian culture and assess the damage that’s already been done, and many are putting their own lives on the line to save it. The ravaged art and architecture and literature are just a few of the things that Ukrainians are leaving behind, and with them, significant parts of the country’s history and identity. So much has already been lost and is still being lost, both in Ukraine and in so many places all over the world.

In The Library Book, Orlean offers readers a stirring reminder of why books (and art) exist in the first place: “Writing a book, just like building a library, is an act of sheer defiance. It is a declaration that you believe in the persistence of memory.”

Toward the end of the book, she writes:

The library is a whispering post. You don't need to take a book off a shelf to know there is a voice inside that is waiting to speak to you, and behind that was someone who truly believed that if he or she spoke, someone would listen. It was that affirmation that always amazed me. Even the oddest, most peculiar book was written with that kind of courage—the writer's belief that someone would find his or her book important to read. I was struck by how precious and foolish and brave that belief is, and how necessary, and how full of hope it is to collect these books and manuscripts and preserve them. It declares that stories matter, and so does every effort to create something that connects us to one another, and to our past, and to what is still to come.

Preserving, housing, returning, and protecting these works is also precious, foolish, brave, necessary, and an act of hope. I’m glad and grateful that Maria Prymachenko is getting the attention she should for the incalculable loss of her paintings. She deserves it, and so do all the painters, authors, architects, storytellers, and artists whose work has been eliminated in the senseless pursuit of power and dominance. There’s a rich world of culture we can never recover and civilizations, customs, ways of life, ideas, and traditions we’ll never know. The very least we can do is talk about, appreciate, and try to retain their memory when they’re gone, which in itself is a heartbreaking and intolerable truth.

I was a senior in high school when the National Museum of Iraq was looted and I still recall having a visceral emotional reaction to it. In a world full of barbarism, unkindness, and unfairness, there is something existential about the erasure of culture and art. It just resonates at a different frequency. This is all so heartbreaking and such a waste for nothing and no one.