"The Last Time I Felt 'Young' Was When I Was Eight Years Old": Living Through War in Gaza

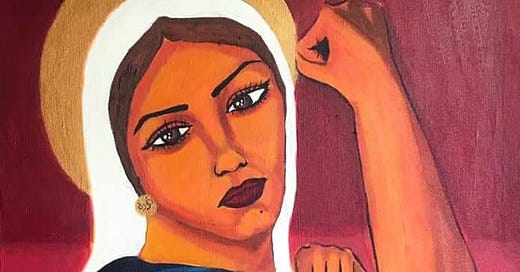

An interview with Gaza artist Malak Mattar.

This piece by journalist Eoin Higgins was originally published on The Flashpoint, which, like Discourse Blog, is part of the Discontents media collective. To subscribe to The Flashpoint, please click here.

Malak Mattar came home to visit her family in Gaza City in March for the holidays. Two months later the bombs began to fall.

The 21-year-old artist, who was born and raised in Gaza, spent the last few years at university in Istanbul, Turkey.

I talked to Mattar on Sunday as she prepared to spend another night suffering under Israel's bombardment. We discussed the current bombing campaign, the wars she's suffered under, and the generational trauma faced by the over 2 million residents packed into the Gaza Strip who are unable to leave.

I'll be releasing the full audio of our conversation for subscribers later in the week. I recommend you give it a listen.

"Now the city is getting erased"

The situation in Gaza is dire. Israel’s bombing campaign is leaving thousands homeless and hundreds dead.

“People right now, while I'm speaking to you, they are under the rubble and the ambulances are not able to reach them because Israel not only bombed their houses, but they bombed the roads around the houses,” Mattar said.

The Gaza Strip is densely populated. Over 2 million people live in the territory, which is about 25 miles long and on average five miles wide. Despite high levels of education, unemployment hovers around 50% due to the occupation. Nearly half of the population is under 18. One of the most densely populated regions in the world, Gaza is under siege from every direction—even the sea, where Israel’s navy keeps the population from straying too far into the water.

And while the Israeli military touts its use of warnings as evidence that it’s doing all it can to limit civilian deaths, that’s not the reality.

“Even when they say evacuation, they only mean five to ten minutes where you have to leave everything behind you and keep running,” Mattar said.

The current round of attacks has been devastating, killing over 219 people, including more than 60 children. Though there’s been more criticism of Israel from the international community than usual, the US government—Israel’s strongest partner—has thus far refused to step in.

That’s nothing new, said Mattar. The Gaza Strip has been left to the mercy of Israel for a long time. The effects are clear in the territory’s poor water filtration, lack of power, and the people’s inability to leave the 365 square kilometer prison. The siege, which began in 2006, shows no sign of ending soon.

"I lived 15 years under the siege,” Mattar said. “I can't really remember if I ever had a full hour of electricity… I'm not truly ready to live another 15 years in this situation. And now the city is getting erased, the landmarks of the city are getting erased. And I'm afraid I will walk in the streets of Gaza and the streets of the most important places where I had the most beautiful memories. And I won't be able to recognize the place.”

“I was not able to speak a word for years”

Mattar recounted a life marred by war.

“The last time I felt ‘young’ was when I was eight years old,” she said.

The Gaza War of 2008-2009 killed over 1,100 people in the Palestinian territory. Matttar was eight during the fighting. It took a long time before she got over what had happened.

“I was not able to speak a word for years,” Mattar said. “I was not able to communicate. I was not able to speak with people and even have a human interaction, because I saw human beings around me as monsters. I didn't see humans as humans.”

Wars in 2012 and 2014 followed, bringing with them more trauma and pain. After 2014, Mattar used painting and drawing to process and heal from the trauma.

That launched her art career. She started exhibiting her work, which critics have likened to Frida Kahlo’s art, and in 2017 got a visa to study in Turkey.

“I live in an open air prison"

It took months to get out of Gaza due to the Egyptian and Israeli military blockades.

“I live in an open air prison,” Mattar said. “And this is not a metaphor. This is the reality, that the Gaza Strip lies beside the sea and even the sea is occupied. So we are only allowed to have access to a few miles of the sea. And if you cross it, you get killed.”

She tried to return over the past four years but wasn’t able to—but two months ago, the border was open and things in Gaza seemed to be improving. Mattar came home to visit her loved ones and attend school remotely.

Then, on May 10, after a number of incidents including Israeli police raiding the holy Al Aqsa mosque during Ramadan—a knowingly provocative move—Israel went to war with Gaza again.

“I would just call it a massacre because honestly what I see now is beyond conflict, is beyond war,” Mattar told me. “It's actually a massacre against the Palestinians.”

"Like opening the wound that has been closed"

Going back to Turkey to finish school will take another months-long process, but Mattar isn’t even sure she’ll live that long, a testament to the reality of living under the occupation and in a “constant state of fear and anxiety.”

“You never feel safe and it's something in your subconscious, you know, that there's something going to happen,” she said.

The bombs come from every direction, said Mattar, who lives by the sea. She told me that the missiles launched from the water are the worst for her because they sound like they’re right outside of her window.

When Israel destroys buildings in Gaza it also destroys surrounding areas, said Mattar.

“Imagine having this huge building in a very dense area where it's surrounded with many buildings,” she explained. “When it fell down, it also destroyed the neighborhood… other buildings were destroyed, too.”

I asked Mattar what it’s like for her and other young people in Gaza, living with the tension from a constant state of war. She told me that it was “the worst thing that could ever happen to any human being, you start losing sense of life.”

“It took me seven years to process what happened in 2014 with therapy, which I was very lucky to have, extremely lucky,” Mattar said, adding that in Turkey her artwork began to have a playfulness and joyfulness it had been missing.

“But coming back here, it felt like opening the wound that has been closed,” she told me. “Like, I don't know if that makes sense or that's so cliche, but I'm just trying to say that just living this again, it's just very triggering."