The Cursed Roots of Silicon Valley

An interview with Malcolm Harris about his book 'Palo Alto.'

This piece was originally published on Skipped History, a Substack blog in which satirist Ben Tumin speaks to leading historians about the overlooked and under-examined events, movements, and people that shaped American history. To subscribe to Skipped History, please click here.

by Ben Tumin for Skipped History

With the world aflutter about AI technology, Silicon Valley Bank going belly up, and legal proceedings around the collapsed cryptocurrency exchange FTX, I spoke with Malcolm Harris, author of Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World.

Malcolm and I went back a few millennia to contextualize and uncover a virulent, prejudicial ethos that has shaped Palo Alto, home of the tech industry, since its founding. A transcript edited for clarity is below. If you upgrade to a paying subscription, you can also listen to the audio of the conversation, which includes Malcolm expounding further on just about everything in the transcript, as well as his compelling argument for returning Stanford’s campus to the Muwekma Ohlone.

Ben: Malcolm, thank you so much for being here.

MH: Thank you so much for having me.

Ben: Of course! Today I'd like to explore what you present as “the curse” of Palo Alto, both on itself and the world.

To begin, let’s discuss the people who inhabited California long before settlers arrived.

MH: Right, when you're talking about Anglo-American California, you have to step back and talk about not just the Spanish and Mexican periods that preceded it, but pre-contact California.

Estimates now have 300,000 Indigenous people living in California for millennia before Spanish colonization. The political nature of the Indigenous communities of California, particularly Northern California and the Bay Area, was stunning.

Ben: As you write, California was home to “one of the densest concentrations of human linguistic and cultural diversity scholars have ever been able to reconstruct anywhere in world history.”

MH: And we still don't quite understand the complexity of the political and social structures of these societies.

Spanish colonization was devastating for California’s Indigenous population, decreasing the population by around half to 150,000 people. Still, Indigenous societies endured well into the 19th century, which I think is really important to note. California's self-justifying ideology blames the Spanish for the genocide of Indigenous people and then holds that Anglo-Americans showed up and kicked out the Spanish without any blood on their hands, but that's not what happened.

As the gold rush began in 1849, state-sanctioned murder gangs took over California based on the pattern of Texas. During the Civil War, California was home to some of the most egregious colonial violence in US history. That's how Palo Alto was able to emerge on what had long been the homeland of the Muwekma Ohlone.

Ben: We explored Texas history recently with Professor Gerald Horne, and one of the takeaways from that conversation was the sheer scale of violence in Texas. To think such violence extended to California and even perhaps exceeded it is astonishing.

Let’s shift to the exceptionally unexceptional founder of Palo Alto, Leland Stanford. How did he end up there?

MH: Leland Stanford, originally from New York, was the least competent of an early group of capitalists to arrive in California. This group, who later called themselves the Associates, grew rich from running the Central Pacific and Southern Pacific railroads, which brought white settlers to the West. Leland was the dumbest of the Associates, so his buddies made him the public face of the company to take the heat for a pyramid scheme they were running.

And though Leland dodged a federal investigation (by dying before it was completed), he faced a lot of heat from workers who, during the 1870s, rallied outside his house in San Francisco. Leland wasn’t that worried—again, he wasn’t too smart—but other people were worried for him. So Leland bought a big piece of land in the South Bay, moved there with his wife, Jane and their son, and created the suburb we now know as Palo Alto (named after a tall tree), where they were far better insulated from the class tensions of the city.

Ben: And Leland became governor of California at one point, right? I remember you noting that he went by “governor” for the rest of his life.

MH: Yep. He served one relatively undistinguished term (and later served as senator). One of the few things he did as governor was fund the genocidal militia campaigns.

Ben: Another reminder to never trust anybody who chooses to maintain a title for the entirety of their lives (Queen Bey excepted).

Obviously, the name “Stanford” sounds familiar. Can you discuss the founding of the university?

MH: In 1884, Jane and Leland’s son suddenly died, so they decided to take the privileges that they were going to endow their son with and spread them to “the children of California” (i.e. the children of other members of their settler class). They founded Stanford the following year, but it was really the first president whom the Stanfords recruited, David Starr Jordan, who set the direction for the kind of university Stanford would become.

Ben: You describe him as a “school administrator committed above all to the genetic future of the white race.”

MH: Jordan was not just a eugenicist, but one of the senior eugenicists in the world, and in his mind, the onset of World War I presented one of the greatest threats yet to the white race. He recruited new faculty to Stanford to develop eugenic strategies for fighting the war, including most impactfully a guy named Lewis Terman.

Terman brought this technology called the IQ test from France to the United States and reformatted it at Stanford into what we now call the Stanford Benet IQ test. The goal was to figure out how to ensure that supposed A-students were at college doing reserve office training while C-students were on the front lines getting shot and shooting.

The military adopted the IQ test. From the beginning, it was based on racial pseudoscience, intended to send people of color to the front lines.

Ben: In the book, you include a sample question from the IQ test: “What is Christy Mathewson’s job?” Answer: pitcher for the New York Giants.

I'm a big Yankee fan, as well as a fantasy baseball player, and I promise you that knowledge of obscure baseball statistics is inversely proportional to one’s ability to function as a contributing member of society.

MH: Ha! The tests were totally arbitrary, as many scientists at the time pointed out. However, they went into mass use, and though we don’t think of California as the laboratory for the construction of whiteness, it really was.

Ben: One thing that's really interesting about your book, too, is that it’s not just a history of California, but a global history as well.

Can you discuss how after the world wars, Palo Alto became “a conduit for the production of an outsourced capitalist planet?”

MH: Absolutely. Stanford students and faculty and early Palo Alto companies helped develop the aviation technology that later culminated in the raids over Tokyo and Germany during World War II.

The areas that were bombed became the real centers of growth for the post-war era, and the electronics industry in particular moved in as soon as the war was over. For example, Hewlett Packard, founded by Stanford graduates, built their first overseas factories immediately in the bombed-out areas of Japan and Germany.

This was part of a new American policy of building up countries as ramparts against what was now the new threat, global communism. During the Cold War, throughout the developing world, American companies and Silicon Valley firms especially replicated this dynamic, going into foreign countries, taking advantage of unsettled labor situations (or intentionally destabilizing labor situations), and saying, alright, now you’re going to work to the advantage of the US economy.

This practice set the tone for more famous tech companies that came along later like Apple to outsource their work.

Ben: Related, you say that innovators in computer technology became “the tools that got capital from the crisis of the 1960s to the ‘greed is good’ 80s.”

Can you elaborate on that crisis, and how computer nerds fit into the story?

MH: The 60s were explosive, both in the US and around the world. The global decolonization movement had stepped up, picked up guns, and started to win territory, right? It began to wind back control of whole societies, whole continents.

And this movement, which included the Black Power movement in the US, was very much a threat to the status quo of white power. For the litany of Californians who still believed in white hegemony, this was a problem similar to the one that David Starr Jordan and Lewis Terman perceived earlier in the century: How do you maintain inequality in a world that is globalized?

That brings us to the nerds. We don't often link the creation of the personal computer to this problem, but they're definitely associated.

Consider for example what it meant to be in a private school in the late 60s and early 70s in segregated American enclaves. Pulling your kids out of public institutions and placing them into private schools that were white-only or that could exclude non-white people at much higher rates, thereby concentrating privilege within those institutions, was very much a white power solution to the threat of integration.

I talk about Bill Gates and Paul Allen within this context because they attended just such a school, the Lakeside School in Seattle, at the same time that Stokely Carmichael was in town rallying nearby Black students about the need for integration and sharing of resources.

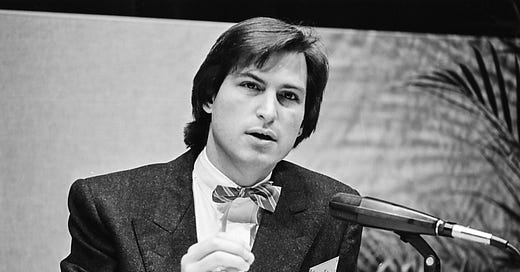

The mentality to pull out of the city, go to the suburbs, and go to private schools can’t be separated from the mentality to shrink computers down, as Steve Jobs did at Apple, or to privatize computer software, as Gates and Allen did at Microsoft. Effectively, Gates, Allen, Jobs, and other so-called “geniuses” made computer access a private privilege. In a world that was getting rapidly worse for most people, they weren’t serving the public but themselves, and they got rich from it.

Ben: I've never felt such antagonism towards my computer as I did when reading your analysis.

Apple and Microsoft have made a lot of money but many celebrated Silicon Valley companies have never turned a profit. Can you discuss why you think the historical trajectory of entrepreneurialism and Palo Alto has taken a turn for the “dumb”?

MH: Sure. Over the last fifteen or twenty years, people have gotten rich by selling failing businesses at the right time or by selling promises that companies will have access to lots of funds in the future. So, Google made money. Facebook made some money, but Uber's never made any money, right? Stripe has never made any money.

But these companies have still made financiers rich, either because the investors sold their shares to other people or maintained stakes in now-public companies that are worth billions, even though the companies have never produced anything in the productive sense of the economy.

And so that's where I talk about it getting stupid. In the early 20th century, the finance layer underlying the Bay Area business community could look at the future of California business and say, yeah, we're in on this, we're in on farmland, we're in on the water rights, we're in on the movie industry, we’re in on the radio industry.

These were all real growth areas, but now, tech founders are continually rewarded for their failure to produce anything.

Ben: I wish I’d been rewarded for the same.

MH: Or consider the background of Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, which is more or less a series of catastrophes—bad business racked up on top of bad business and failure upon failure. In this finance profit era, those all turn out to be successes, and he’s now reaching iconographic status.

I think the kind of bank run that we saw recently at Silicon Valley Bank reveals how fickle this kind of success is, as well as signifies diminishing faith in the profitable expansion of this dumb finance-tech business model.

Ben: The fickleness of the dynamic also seems to represent an extension of Palo Alto’s history as a place rooted in bad science, reckless speculation, and outright fraud dating back to the days of Leland Stanford, and bringing us full circle.

Malcolm, this has been a pleasure. Thank you so much for your work and your time today.

MH: Thanks again! I had a great time.