The American Killing Machine and Us

This country was built on war, and that foundation shows no signs of wavering.

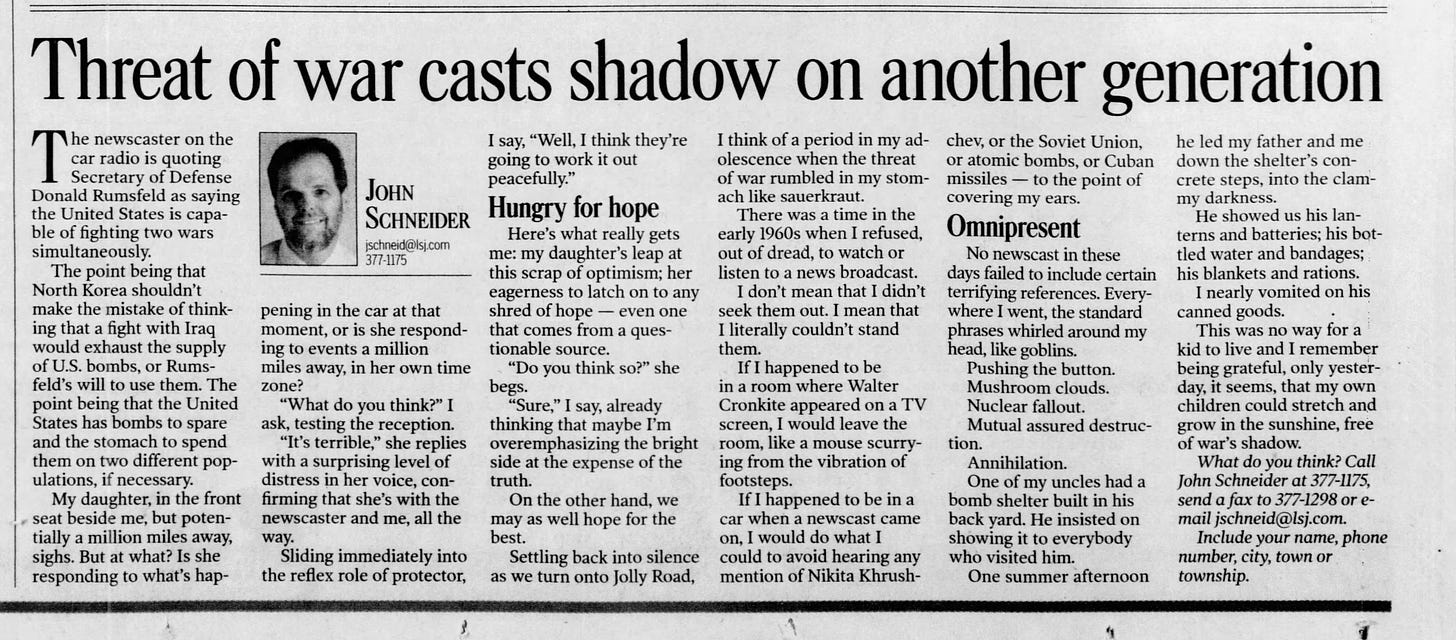

I have a very clear memory of sitting in the passenger seat of my dad’s car as a teenager and listening to Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld on the radio. It was 2003, we were almost certainly listening to NPR, and Rumsfeld was talking about the United States’ ability to simultaneously wage war on Iraq and North Korea if necessary. We were about five minutes from home, but I remember feeling distinctly unsafe. I wasn’t afraid of any immediate bodily harm; it was a purely existential panic. A kind of thousand-yard stare steeped in dread that only a first fateful meeting of senseless violence and a newly adult brain can produce.

My dad and I talked about it as we drove, and he reassured me that things were going to be okay. But part of why I remember this so well is because he wrote an article about it in the local newspaper. In the story, he admits to steering the conversation toward optimism, potentially at the expense of truth. He admits to having his own crisis in adolescence about the threat of war, the unsettling experience of visiting his uncle’s bomb shelter, and about wishing his kids were free from the hell of such anxieties.

It’s now 21 years later and nothing on that front has changed. America is still the highly productive war machine it’s always been. My story of realizing that fact certainly isn’t novel, but it’s mine, and I’ve been thinking about it a lot this week, and about the immense emotional weight I felt back then. I thought about it when Israel dropped bombs on Lebanon last week, and when Iran sent missiles into Israel. It’s like my brain was reverting back to that car seat in 2003, wondering whether there was a chance something bigger—something more personal—was coming for me.

Based on conversations I’ve had this week, I don’t think I’m alone. Even after a year of horrific violence and mass death in Gaza—a year of mourning, anger, and an undeniable shift in the way much of the world sees the struggle for Palestinian liberation—it still feels like panic and dread hit new levels this week. As Jack put it so perfectly to me yesterday, “We seem to have gone past despair and into delirium.”

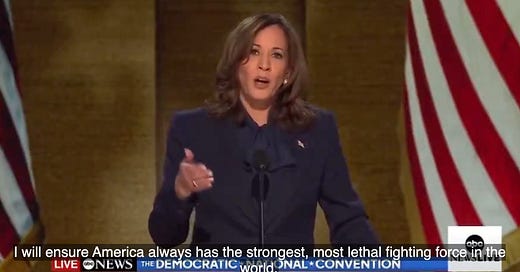

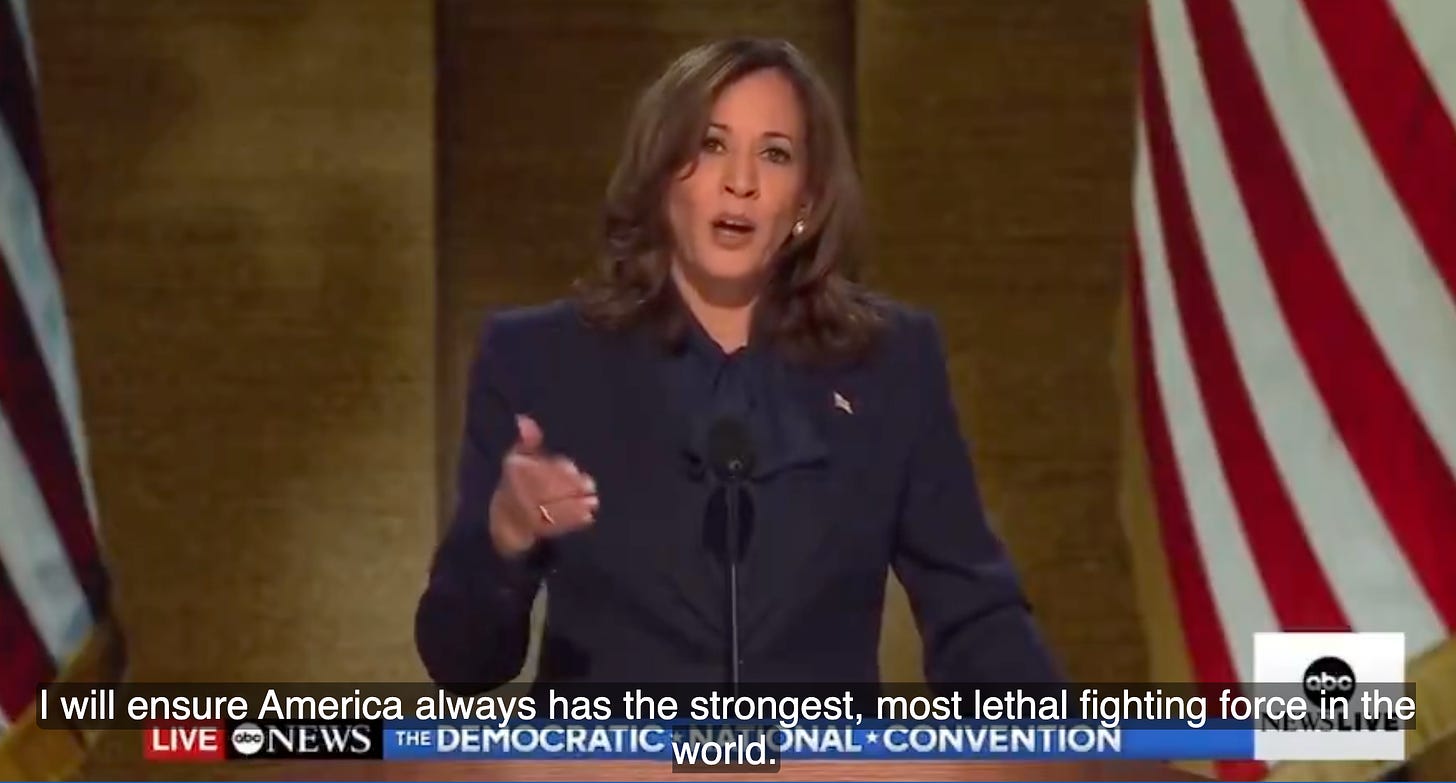

It certainly doesn’t help that we are 32 days from a presidential election in which both candidates are unflinchingly committed to upholding the military-industrial complex that defines this country. Kamala Harris has vowed to “ensure America always has the strongest, most lethal fighting force in the world” (a set of words that I still find almost comically barbaric) and earlier this week, Tim Walz engaged in some light back-and-forth about issues like, “Would you nuke a country, yes or no?”

It is not news to anyone reading this blog that we live in a very violent country with a violent legacy. Just this year, we’ve had: hundreds of mass shootings, cops shooting subway fare evaders and choking unhoused New Yorkers to death, hate groups swarming Springfield, Ohio to terrorize Haitian residents at the behest of a few lunatics, ICE training civilians to surveil and shoot other civilians, the Army testing killer robot dogs, and defense contractors continuing to do big business, thanks in part to the largest economy in the world’s decision to fund the genocide of the Palestinian people. The business of war is very lucrative indeed.

This violence permeates our laws, our systems, our rhetoric, our society, and our bones. It’s not news (or perhaps better stated it is always the news), and the injustices are often too much to bear, and yet we do, all the time. We compartmentalize until we can’t—until the killing machine becomes too overwhelming, and we can see that, in one way or another, that machine is also coming for us.

I’ve become vegan in the last few years after being vegetarian for years prior (OMG PLEASE DON’T STOP READING, I SWEAR TO GOD I’M NOT TRYING TO CONVERT YOU), and my experience matches with stories I’ve seen chronicled elsewhere. When I became vegetarian, the idea of ever eating meat again became repulsive to me. When I ventured into veganism, the idea of ever consuming animal products of any kind became similarly repulsive. I didn’t anticipate it at all, and of course it’s not universal, but there’s something about that shift that makes total sense upon reflection. When you decide to be that intentional about the nature of your relationship to the mass violence and exploitation of animals, it makes the moral question at the center of things much clearer, and much more difficult to sidestep.

I don’t mean to suggest that I’m morally superior to meat-eaters, or that the way we think about violence towards human beings is exactly the same, but these things are inevitably intertwined. Every day, each of us has to navigate the immense violence that powers our world. We all have to figure out how to handle the weight of all that violence without losing our minds. We all choose, in one way or another, to look away from something terrible. The endless nature of combat and ambient violence in everyday life in the United States is part of what keeps us desensitized and inured. Violence begets violence. It’s an insatiable beast. It’s all most of us know.

But sometimes, we have to look—to confront this violence and its role in our lives. As we approach the anniversary of October 7th, I’ve been thinking a lot about the hundreds of days of violence that followed it and the thousands of days of violence that preceded it. How in those spans of ceaseless savagery, certain moments still broke through and shook me beyond the regular horrors of mass murder (an insane, but true sentence). It’s proof, I guess, that I, along with hundreds of thousands of others, aren’t totally brainwashed by this culture of brutality.

After October 7th, we’ll continue to march toward election day, a day that is—as Jack put it—increasingly sending me past despair and into delirium. Despite everything, it feels as though the cycles of the past are repeating.

In 2003, I sighed and fretted, and believed that maybe everything would turn out fine. It did for me, in part because I’m not Afghani, or North Korean, or Pakistani, or Somali, or Iraqi, or Syrian, or Palestinian. I can’t bring myself to hope, as my father did, that things might be different for the generations to come. I’m not sure what’s reasonable to hope for right now if I’m being completely honest. (I think often about a sort of secular rapture-but-for-the-bad-people situation, but that’s my teenage self grasping at straws again.)

The hope I do have comes from the unimpeachable truth that not all countries function this way, and that many millions of people in this country don’t wish to live this way either. A different reality exists elsewhere, and maybe it can for us. The anger remains more powerful than the despair, and I find comfort in knowing that lot of us are grasping for each other in the dark. It’s not enough to save the many people who have died and will continue to die at the hands of this country, but it’s not the end of the story. It’s not the end as long as we believe something better is possible.

Thank you for this, Caitlin. Grasping for likeminded and despairing others indeed.

My wife has wanted to leave the country for some time. It's very difficult to argue that she's incorrect in that impulse. In related news, it's very difficult not to feel incredibly sad these days.