Rubber Bullets Don’t Fire Themselves

The media keeps using language that obscures the reality of police violence.

On Sunday, demonstrators in Washington D.C. gathered in Lafayette Square across from the White House to protest police brutality and the murder of George Floyd. There, police used flash-bangs and shot tear gas at demonstrators.

In a now-deleted tweet, here’s how local station WUSA9 described the scene:

As people on Twitter immediately noted, the phrasing here was odd at best, as pepper spray, an inanimate object, lacks the agency or ability to spray itself. But the use of the passive voice here wasn’t limited to the social media copy. Here are a few other examples specifically surrounding tear gas from the station’s accompanying story, which provided a stream of live updates over the weekend and into Monday.

-“...tear gas has been deployed where protesters remain.”

-“Tear gas is being deployed.”

-“After being hit with tear gas, Matt Gregory and his crew says they are doing better after protesters put milk in his eyes.”

-“As they move the protestors down H street, police fired a combination of tear gas and flashbangs.”

-“WUSA9 Reporter Matt Gregory and Photographer James Hash were tear-gassed on Live TV while reporting at the scene of the protest.”

When read from a purely grammatical level, these updates would reasonably lead you to believe that half of the time, tear gas sprays itself. But it doesn’t, of course. Cops spray it.

This kind of language has been everywhere in the reporting on the protests and the violence of the past few days.

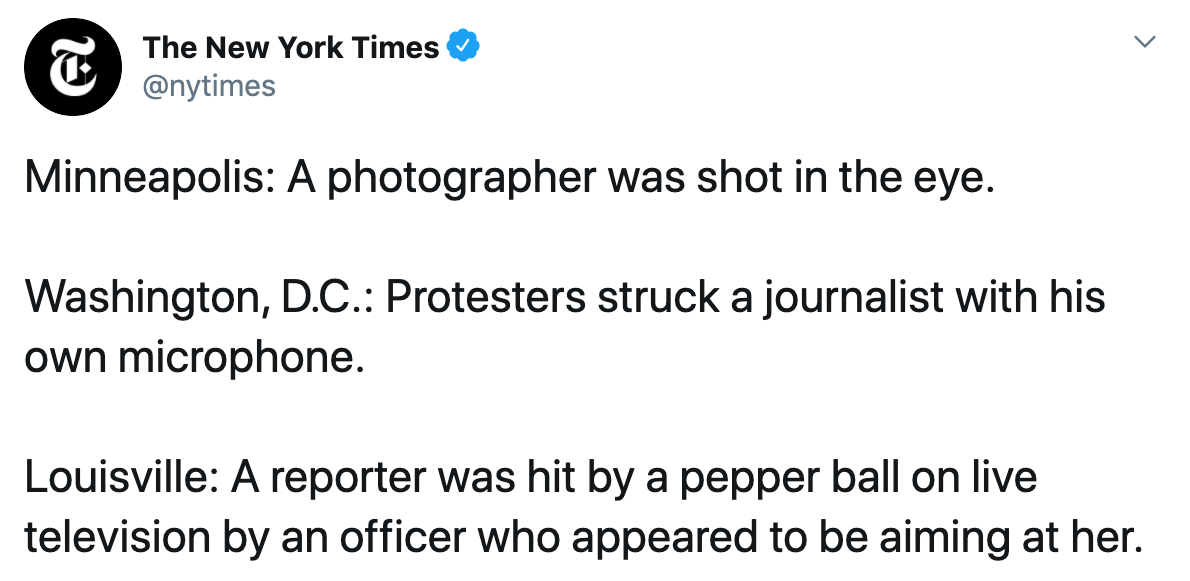

On Saturday, The New York Times published a piece about violence suffered by journalists while covering the protests.

This is how the story was teased on Twitter:

If there was any doubt (and it would be fair if you had some doubt), police shot the photographer, Linda Tirado, who is now permanently blind in her left eye.

And who shot the reporter in Louisville, you ask? Also the police, though the description in the story itself is cautious to avoid saying so directly.

It reads: “A television reporter in Louisville, Ky., was hit by a pepper ball on live television by an officer who appeared to be aiming at her, causing her to exclaim on the air: ‘I’m getting shot! I’m getting shot!’”

Let’s read that again, shall we: “Was hit by a pepper ball on live television by an officer who appeared to be aiming at her.”

There is video of this. It shows the police officer aiming directly at the camera, not “appearing” to do so. The story links to it and you can watch it and see for yourself.

There’s no need to phrase things this way, whether in the tweet or the story. It’s a series of choices the Times made, and, taken together, it conveys a pretty clear message: State-sanctioned violence is usually passive, and is either attributed to no one or is described in the haziest possible way. Protest violence is usually active, the fault lies with the protestors, and the circumstances are rarely in doubt.

None of this is new for the Times—a paper known to chronically insist on both-sides coverage, operate as you would when navigating a conversation with an unhinged relative at Thanksgiving, and generally treat even the most clear-cut subjects like a third-rail topic in a manner that any politician would find admirable. (The current controversy over the paper’s awful framing of Donald Trump’s assault on protesters is a great example of this.)

Here are a few more examples of this kind of institutional timidity, manifested in tweets, all from the last week alone.

The linguistic gymnastics at work here are truly a marvel. It takes incredible editing athleticism and pure effort to avoid saying the most clear, direct thing, which is what the news is supposed to do. Yet they manage to do it over and over again. Why?

Yes, covering breaking news—especially when lives are at risk, especially when things are developing quickly, especially in the midst of sprawling, chaotic situations—requires care. Accuracy matters. And yes, most of these large outlets will have lawyers telling them to avoid definitive terms like “murder.” But this isn’t about facts. And it’s not about legal niceties—because even if you feel like you can’t say a cop “murdered” someone, what’s stopping you from saying they “killed” someone?

It’s about framing. Taking agency away from the police in instances where they conclusively had it is a bias-revealing decision. Passive phrasing often asks you to question if what you’re seeing with your own eyes is real. Any attempt to be “careful,” or avoid misattributing actions, or steer clear of being “political” (a bullshit explanation to begin with) is itself a political choice.

The news is not neutral. It never has been. That idea is a myth and delusion that can only be held by people privileged enough to feel they can exist outside politics. The news has always been political and choosing your news source has always been a political act. Even as a dumb teenager, I can remember clocking when another family had a copy of The Washington Post on the kitchen table or NPR on the radio—I already had ideas about what those choices meant. At this point, in 2020, you should be suspicious of any source that still touts non-bias as some sort of badge of honor. You can tell the truth and have opinions; those things are not mutually exclusive.

Many outlets over the weekend managed to get it right without couching information in a labyrinth of words to avoid saying anything at all. They might not claim the title of America’s “newspaper of record,” but if having that designation means hobbling your own work, the title might not be worth having.

Rubber bullets don’t fire themselves. Pepper spray doesn’t spray itself. Batons don’t wield themselves. None of it is a matter of opinion and phrasing it as such is not an oversight, or a means of mindful, responsible reporting. It’s a failure of reporting. It’s insidious. And it enables larger narratives about protestors inciting violence, when time and time again we’ve seen peaceful protests only turn violent when cops arrive. The passive voice enables police, enables systemic violence, and enables the president of the United States to tear gas a crowd on national television, unconcerned with consequences. He didn’t do it, not technically. No one did.

And George Floyd wasn’t killed by police. His death was “a homicide that occurred while he was being restrained by police.”

The passive voice is a means of disarmament. You can’t fight an enemy that doesn’t exist. Consider why a news source would do that. And if they pretend that that decision was itself a passive one, that’s a good way to tell whose side they’re on.