This piece by journalist Libby Watson was originally published on her Substack, Sick Note. Sick Note, like Discourse Blog, is part of the Discontents media collective. Subscribe to Sick Note here.

by Libby Watson for Sick Note

One year ago today, I wrote about how much I was struggling with migraines.

I was having quite a time with them; I had a headache or a migraine almost every day so far that month. I barely remember anything about that time, other than that I swung very quickly from feeling excited about starting Sick Note, full of ideas and energy to report them, to feeling overwhelmed by inadequacy and failure. Sure, I had a headache almost all the time; was it really severe enough to stop me working so much, though? Did I deserve to go back to bed, or should I just power through, like other people do? Am I just lazy? As I wrote last year:

It’s not just the days where you truly could not sit up in bed without crying from pain; it’s the in-between days where you have to decide whether your migraine is bad enough that you can justifiably take the day off, or whether you could actually just cope with it and muddle on. The latter option might well make it worse, setting you up for further days of migraine. The former option might not prevent those later days of migraine anyway; you just don’t know. But it’s the pressures of work, or caring for children, or maintaining your home, or all the other bloody tasks that need to be done, that introduce a non-medical consideration. In an ideal world, every time your head hurt even a little bit, you would rest, to prevent the migraine and because a headache itself is bad.

I know this is a familiar dilemma to migraine sufferers, and I also know that it’s the more luxurious version of the problem. Other people, like the women I talked to for a piece in 2017, don’t just cope with guilt and poorer work quality; these women were choosing between their health and making rent. They were hiding under the desk at work, crying, doing yoga breathing instead of taking meds because they had no health insurance. Knowing all this, it was hard not to additionally feel a big dose of “get over it,” too.

A year on from that post, things are very different. I can’t say I’m happier—my mum is notably dead, for example—or that I have a radically reformed approach to work and self-care. I did not learn to love myself. What I did do was start receiving Vyepti, an intravenous migraine medication, every three months.

In early March 2021, I had my first infusion; I got slightly anxious during the IV insertion, but I was a very brave girl about it. I left and got a posh iced tea, drove home listening to The National very loudly, feeling incredible—it must have been the unseasonably beautiful weather, the post-anxiety adrenaline, and the caffeine. I did no work and went for a long walk. I texted Mum all day about how happy I was, and how good the tea was, and I ordered some to be delivered to take home next time I saw her. A week or so later she went into hospital, and a month later I was picking funeral outfits and saying goodbye to her. Funny how things work. At least we got to drink some of that tea together.

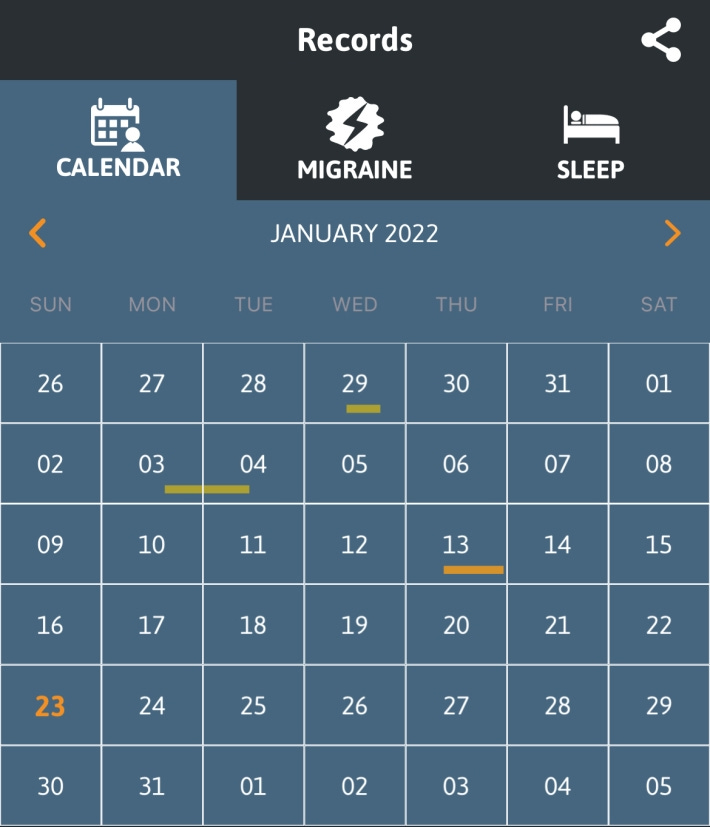

I’ve received Vyepti every three months since then, and while I am not exactly ‘cured’ of migraine—which I don’t expect to ever really happen, though maybe after menopause—my life is unrecognizable compared to last January. I go weeks without severe migraines. I drink coffee every morning, which was unthinkable before. I drink alcohol once or twice week, something I haven’t really tried to do at all since a spectacularly bad migraine in late 2016. The last time I used an injectable sumatriptan, which I only use when I’m having a very bad one because it is like hitting yourself in the head with a fridge, was early November. I know this because I record my migraines in the app Migraine Buddy, and these records sometimes speak for themselves. Here’s this January, as of today:

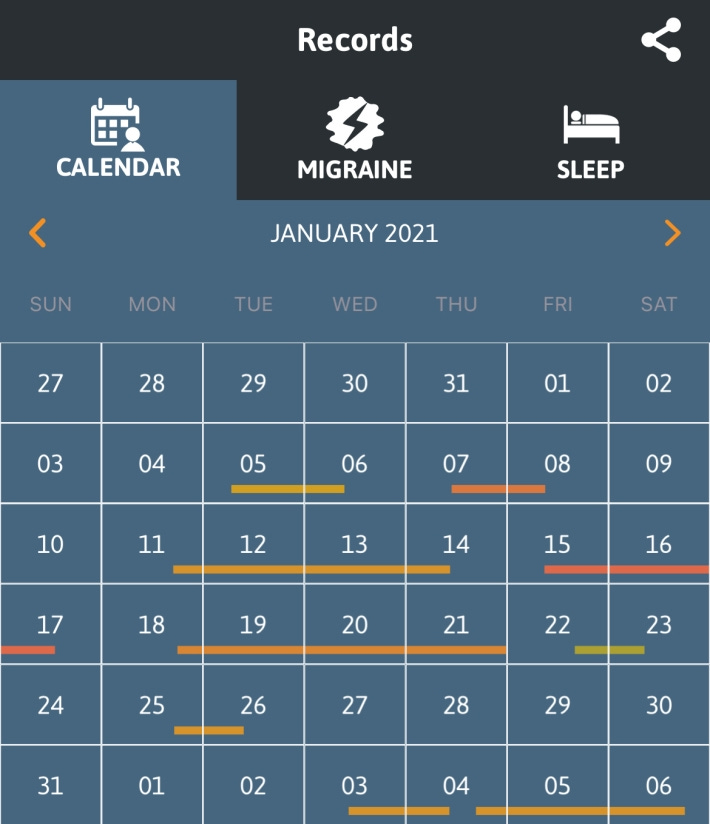

Just a couple of little guys. Compared to last January:

It’s a similar story for December. I am so much better, since about mid-November.

To be clear, it might not all be thanks to Vyepti. Maybe my daily coffee habit is part of it, since some swear by caffeine for migraine. I’m taking a higher dose of Wellbutrin for depression, and it is definitely working (there is a well-established link between migraine and depression). Maybe my weekly therapy sessions are helping on that front, too. Maybe taking all of December off because of that depression and starting slowly again in January did something; maybe February will be a huge migraine disaster. Maybe I was always going to get fewer migraines once I hit 31 and a half, as part of God’s Plan. So little is known about the causes of migraine in the first place that figuring this stuff out is a bit of a fool’s errand.

But the change is so remarkable and unusual that I have to think it’s largely due to the Vyepti. I haven’t had so few migraines since I was about 15, maybe younger. No preventative migraine medication that I’ve used over the years has had this sort of effect, and I will name them now to show you what I mean: pizotifen, amitriptyline, atenolol, verapamil, topiramate, Botox. Each tried and failed, after a period of months and various side effects. Even Aimovig, part of the same class of drugs as Vyepti, didn’t help this much, though it did help significantly at first and then tail off, which I’m not going to think about. For 16 years it has been a multi-day migraine roughly once a week, and sometimes worse, almost every day. I took the abortive triptans often, and if I tried to avoid it the migraine usually just got worse until I took one anyway. I had to take a naratriptan about 10 days ago, for the first more-severe one in weeks, and I couldn’t believe how shitty and tired it made me feel. Is that how I was living, for years?

What is this miracle drug, then? Vyepti is a calcitonin gene-related peptide blocker, a class of migraine drug that first hit the market in 2018. (I wrote about that at the time, too.) Its non-brand name is eptinezumab; the “mab” ending tells you it’s a monoclonal antibody, like those expensive Covid treatments. Monoclonal antibodies are ‘biologics,’ meaning they’re created using living cells in a lab, and the number of these drugs approved each year is increasing over time. Mabs have had a massive impact on my life: Mum received immunotherapy for her cancer for two years, a drug called pembrolizumab or Keytruda. Two years of remarkable health, visits to DC, evenings of telly together. It wasn’t too long after she was no longer eligible for it that she started getting sicker, and she died within a year of stopping it.

Mabs are also very expensive. As with so many new (and old) drugs, that’s where the problems begin.

I get Vyepti infusions at the same neurology clinic in Friendship Heights where I see my neurology nurse practitioner. It’s always a pleasant experience. The nurse is extremely nice. There’s a big comfy chair, and the nurse keeps the lights low and talks quietly. I listen to a podcast. I think about Mum in her immunotherapy chair, in the hospital back home.

Each visit is a $50 co-pay, on my Gold plan that I bought on the marketplace ($491 a month this year, with a $300 subsidy from Substack). My explanation of benefits shows that the provider’s negotiated rate with CareFirst is $78.11 for the office visit, but the un-negotiated rate is $191. The cost of the drug itself is $7020, with a negotiated rate of $4689, for the 300mg dose I get. I pay none of that because I have no deductible. It is very interesting to note that the list price of vyepti is $1532.38 for a 100 mg/mL vial, or $4597.14 for three like I get—very close to that negotiated rate—but the hospital listed $7020 as the price before insurance discounts. That’s so much more money! If you’re a hospital and you’re paying thousands more than the list price for drugs, I’d look into that, because you’re getting robbed! (They’re not; they’re just lying.)

As with many of these new and expensive drugs, Vyepti has a co-pay program, allowing eligible patients to pay “as little as $5 a month.” There’s a maximum annual limit of $4000 in available assistance, or less than what it costs my insurance for one max-dose infusion, and you are not eligible if you’re uninsured or on government programs like Medicaid and Medicare. Under President Trump, a rule change allowed insurance companies to not count these assistance programs towards your deductible, leaving patients with expensive medications on the hook for thousands more. This was supposed to encourage the use of cheaper generics, which do not always exist and are not always cheap. The Biden administration kept the rule; “we encourage issuers and group health plans to consider the flexibility to exclude these amounts,” they said, to limit costs.

There is no generic (‘biosimilar,’ for biologics) alternative to Vyepti, and the patent doesn’t expire til the mid-2030s. It is going to cost this much and more for years, and there’s no one and nothing to tell them otherwise, neither the government nor hahaha market forces hahahahaha sorry. It’s just that expensive. A generic could be when it comes, too, as generics are for MS patients like Nick in the interview above.

So what do you do if you are a migraine patient like I was a year ago, getting migraines every day and beating yourself up about it too—but you’re uninsured? Where’s the help for you? Then again, if you’re uninsured, you’re much less likely to have a neurologist who would prescribe Vyepti, or anything. You might not even have heard of it.

What if you’re on Medicare and you can’t afford the 20 percent Part B coinsurance? Or what if you’re insured, but your insurance company just sucks?

Vyepti doesn’t work for everyone as well as it seems to for me, of course. But there are undoubtedly people out there who could be helped by it and who are not able to access it, either because of cost or because they can’t see a neurologist. (In 2018, there were less than 500 headache specialists certified by the United Council of Neurologic Subspecialties.)

I’m still navigating what it means to live without frequent migraines, temporary as that may be. It’s wonderful, though honestly a little confusing and strange. I still pretty much have a hole blown through me by the loss of Mum, so I can’t exactly say I’m Feelin’ Fine overall. I’m slightly terrified of what will happen when I move to Los Angeles in March, away from my treasured migraine specialist and with a new, limited set of insurance plans to choose from. I’ve already requested an appointment with a doctor out there so that I can make sure I don’t miss my next Vyepti, before I have an apartment there, or even know which neighborhood I’ll be in.

But things that I couldn’t do before are now open to me—and without guilt, too. I am not feeling pain, nor living in fear of it when I’m without it. I’m learning about which wines I like. (I take Nurtec, the little guy of the CGRP drugs that you can take both as an abortive and a preventive medication, most of the time I drink—but I only get 8 tablets a month, so I have to be careful. CareFirst should give me more so that I can get tipsy more often and not worry about keeping one for a random migraine. I’m fighting for my right to party.)

I want this life for every chronic migraine sufferer. I know Vyepti isn’t the answer for all of them, but there’s no reason why I should have been able to try it if others can’t. The cost of a drug should not be something a patient ever even hears about, let alone something that determines their access to treatment. It is not beyond the American capacity for innovation to find a way for the state to develop, fund, or even just purchase drugs at a non-insane price. Poor people, who are more likely to suffer migraine in the first place, have as much right to try new drugs as middle or upper income people.

When I tell people about my new life without migraine, I sometimes joke that I love Big Pharma now. In reality, though, Big Pharma loves me: A patient with generous insurance who will toddle along to her infusion every 3 months, generate them $18,000+ of income annually, and depend on them for many years to come.

I bet they’d love it even more if that made people like me afraid. Afraid that any suggested change to the healthcare system, how we pay for drugs, or who gets health insurance might snatch away the medicine we need to have a normal life. Clinging to the narrow path of access that we’ve tottered along, doing everything just to make sure we don’t slip; not looking back to see who pushed us on this rickety bridge, or who else might have fallen off.