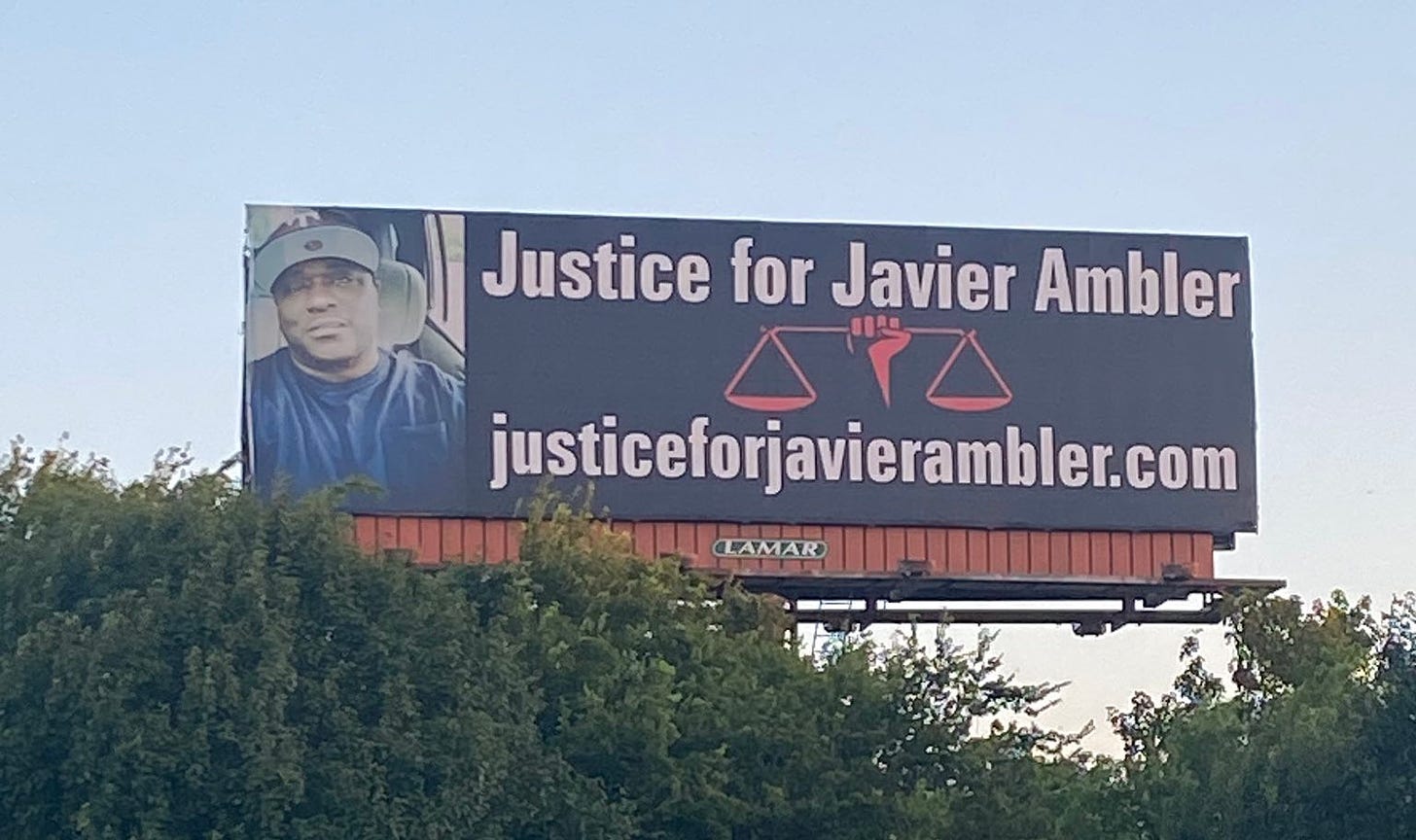

I was driving into Austin yesterday when a billboard caught my eye. A few miles south of the crossover between Williamson and Travis counties, somewhere between the shopping center with one of the first Cinemark theaters in the area and the cemetery where my grandmother is buried, is an advertisement seeking justice for Javier Ambler.

On the left of the billboard is Ambler’s photo, a picture made popular in the local news coverage of his death, and on the right is an illustration of a fist holding up a justice scale. It’s captioned with the phrase “Justice for Javier Ambler,” along with a URL to a website run by his family.

Ambler was killed by Williamson County sheriff’s deputies in March 2019, after deputy J.J. Johnson attempted to pull Ambler over, then chased him for 22 minutes into North Austin, because Ambler hadn’t dimmed his headlights. Ambler crashed his car and as deputies arrested him and tased him, he was recorded by body cameras saying he had congestive heart failure and that he couldn’t breathe. He went unconscious and died at a hospital hours later.

The specific circumstances of Ambler’s death remained murky to both his family and the wider public for over a year. It was only in June 2020 that local publications obtained the body camera footage that showed what had happened to him. Until then, all that was known was that he had died in police custody.

Ambler’s death is all the more disturbing because both Johnson and Zachary Camden, another deputy who tased Ambler, were riding with cameras from the now-canceled A&E police reality TV show Live PD. The show started filming with the Williamson County sheriff’s department in November 2018 after being courted by Sheriff Robert Chody, a lottery-winning millionaire. Though the county’s commissioners ended the contract between the county and Live PD in August 2019, Chody announced in April of this year that he had brought the cameras back in defiance of the order.

Commissioners sued Chody in May, saying that he had “secretly and illegally” restarted the filming. The suit also alleged that Chody told emergency dispatchers not to put deputies filming with Live PD on nearby calls, even if they were a priority. “Instead, these deputies would put themselves on calls that were only of interest to Live PD’s producers without notifying the dispatcher,” the suit claimed, according to the Austin American-Statesman. Within a week of the publishing of the body camera footage in June, A&E announced it was canceling Live PD.

There are many other fucked up things about Ambler’s case — a recent American-Statesman investigation found that Chody’s department was initiating pursuits at a higher rate than other law enforcement agencies in the area that weren’t being filmed — but I guess what struck me the most about this billboard was its mere existence.

When I spotted the billboard, I was so surprised that I turned back to check if Ambler’s face and name were also on the other side (they’re not). But its position along the highway makes sense, even during a pandemic. Ambler’s photo faces the county where his chase started. Ambler himself passed this very spot as the Williamson County sheriff deputy and Live PD crew chased him. It’s a billboard that sees tons of traffic daily — lots of folks live in North Austin or further into the suburbs in Round Rock or Pflugerville or Georgetown, because it’s cheaper, and commute south to their jobs in Austin.

It also seems to be the only billboard of its kind in the area. Ambler’s sister, Kimberly Ambler-Jones, who has been immersed in seeking justice for her brother, tweeted about the billboard when it went up in late July with the hopes that it can stay up for the next 12 weeks. It was fundraised through sales of shirts made by online vintage and customs retailer Klassik Goodzl, which feature Ambler’s image and name along with the phrase “say his name.”

Chody is running for reelection, and the other thing that made the billboard stand out was its contrast to the seemingly infinite signs his campaign has posted throughout Round Rock, where I live. They’re on the corner of every intersection, in fields surrounding grocery stores, churches, and other locations that make for popular polling stations. Chody is, of course, running against defunding the police and “anti-police extremism”; his website touts the arrival of Live PD cameras as something “Robert’s gotten done for you.” (To be clear, Ambler-Jones hasn’t advocated for police defunding, and has focused much of her online messaging on getting justice for her brother, which to her looks like the deputies who killed her brother being held responsible and prosecuted.)

Chody’s name is everywhere, reminding his constituents that he is the face of law and order. He is just. He is what we need. Seeing Ambler’s name, and that contrast, broke my train of thought and fixated my attention. It made me see just how under-scrutinized his story has become by myself, and the other people who live here.

There are cases like Ambler’s in every city in the U.S. There is a Jacob Blake and a George Floyd and a Daniel Prude and a Breonna Taylor. Rarely do we hear about the Blakes and Floyds and Prudes and Taylors — about so much justice undelivered. And even when we do, there is always a Robert Chody, papering the town, insisting that he is still fit for the job, that he deserves another shot.

Update, September 9, 11:36 a.m. ET: In response to an email, Ambler-Jones told Discourse Blog that, though her family would like to keep the billboard up for another four weeks, they don't have the $2,500 to extend the rental — between the billboard and mural they currently have going up for her brother in Downtown Austin, they're choosing to raise funds for the mural.

“The billboard is meant to bring awareness to Javier's case, and to know about his story,” Ambler-Jones wrote. “Most people don't have a clue and this happened in their backyard.”

Photo via JavierAmbler/Twitter