Having Our Dead Bodies Sold Back to Us

Laying out a vision of a death untouched by profit motive.

This piece originally appeared in Luke O’Neil’s newsletter Welcome to Hell World, which, like Discourse Blog, is a member of the Discontents media collective. Click here to subscribe to Welcome to Hell World.

by Harvey Day for Welcome to Hell World

Imagine that you suddenly die tomorrow. Let’s say that as you’re walking downstairs while doom scrolling the latest IPCC news, pondering how you would have died at some later date under climate change, that the cat runs between your legs, trips you, and you tumble to your death. Assuming that you’re like most Americans, you probably never gave much serious thought to what would happen to your body when you exit this mortal coil, much less have written your wishes down. You almost certainly didn’t add burial insurance to your list of monthly expenses.

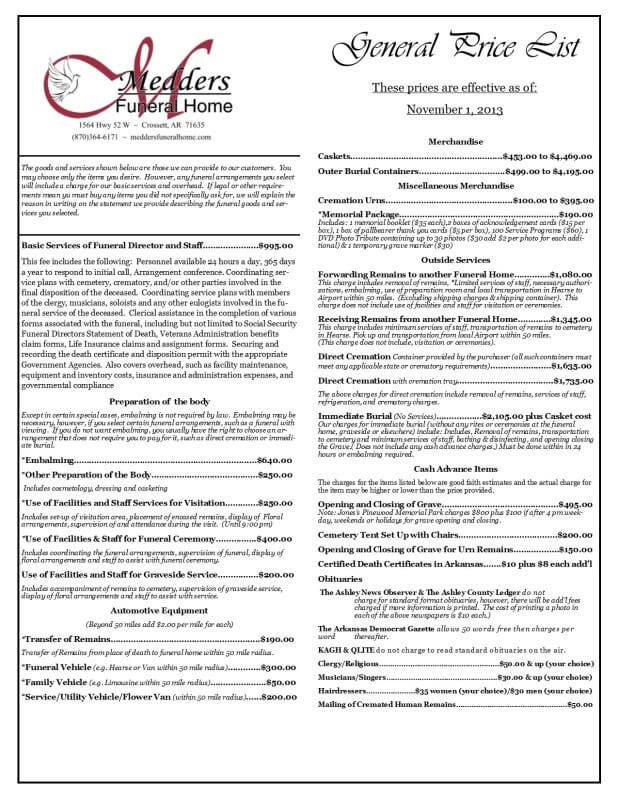

Nevertheless, with your body now beginning its entropic journey, someone who cares for you, someone shocked and grieving, will be tasked with “what to do next.” A few panicked phone calls later they will eventually wind up calling the local funeral home. Perhaps the same one that everyone in the family has used for years. One they trust. At this point a transfer associate will be sent out to retrieve your body ($350) and within hours your loved ones will sit down with a funeral director to plan your disposition.

Maybe you always thought cremation made sense to you, but you never wrote it down or discussed it at all really, and now your mother is insisting the funeral be held in four days so that your cousin from Alabama can take time off work and make the trip. While you’re chilling in the refrigeration room ($100) your family will be agreeing to a basic services fee ($2,040) which covers the cost of filing the death certificate, planning the funeral, and the overhead of the funeral home. After the details are hashed out, the bereaved will be escorted into the Merchandise Room. In their disbelief at the last 24 hours' events, they might not notice the muzak version of Joan Osborne’s “One of Us” being piped in through a speaker tastefully disguised as a potted succulent. Next the funeral director will go over the merits of the various types of materials involved in making a casket and explain which ones have the best chance of keeping out the elements. Wood or metal? Stainless steel, bronze or copper? Full couch or half couch? What about the interior? Would you like tailored, tufted, or shirred? Velvet, satin, or twill? All available in any customizable color, of course.

Your family, physically and emotionally exhausted, and still needing to visit the cemetery to buy your burial plot ($1,774), choose the Whitmire II, a walnut semi-gloss with cream satin interior ($2,466). “A beautiful choice,” the funeral director says for the fourth time that day.

One more thing though. They’ll need an outer burial container, required by the cemetery. It’s a concrete box which will prevent your grave from settling and creating an uneven surface on the lawn, which is very annoying for the landscapers. The Wilbert Monticello model will do nicely ($1,395). Oh, and don’t forget the registry book and memorial cards, a lovely gesture for the mourners ($185).

Perhaps by now the embalmer has arrived to prepare your body for viewing. Dressed in OSHA regulated protective clothing, the embalmer will wash you, stuff your mouth with cotton and wire your jaw shut, and your eyes will be permanently closed with “eye caps,” little pieces of plastic with hooks that grab your eyelids and drag them forever downward. Two incisions will be made in your neck and tubes will be inserted to replace your blood with a mixture of formaldehyde, glutaraldehyde, methanol, ethanol, and phenol. Next, an incision will be made in your abdomen and the various juices and gasses of your organs will be suctioned out and replaced with more embalming fluid. With your blood and bile washed down the drain and decomposition successfully staved off for the next two weeks, you’ll be dressed and a layer of makeup will be applied to make you look as lifelike as possible, lest anyone be reminded at your funeral that you have, in fact, died. ($895).

Your cousin from Birmingham now safely harbored at the Best Western, it is now the night of your visitation ($450) and mourners will quietly file past to remark on how peaceful you look. The next morning your funeral will take place ($450) after which your body will be transported to the cemetery ($325). In the limousine ride there ($50), your girlfriend, dazed with grief and sleepless, might offhandedly think, “Oh shit, was that ‘One of Us’ playing when we were picking out the casket?” Your grave will be opened and closed ($600), your family will depart, and you will have been successfully buried in the “traditional” American style to the tune of $10,630.

In the following weeks, your family, with no room left on the credit cards, will choose a modest headstone to mark your grave for an additional $300.

As an advocate for green burial and divorcing capitalism from death care, when I inform people that much of what I just described above is, in fact, optional, I’m met with a range of responses. One is, “Please, Harvey...we’re eating dinner, do we have to do this now?” Another is a mixture of shock at the cost of a funeral, anger that we can’t even die without racking up debt, and ideas about how they’d do their own burial differently. “You mean, I can actually decompose and become a tree when I die?” people often say.

The other reaction is something akin to disgust, and includes accusations that I believe people should be buried in the backyard like the family dog. Actually, I think that would be great!

The underlying current of this disgust seems to stem from two places: one is resistance to the idea that we should break away from the way things “have always been done,” and the other is a contempt for the idea of death itself. Like individual car ownership instead of mass transit, single-use plastic bags, and ketchup-flavored Pringles, capitalism has spent the past 150 years convincing us to buy the things we just can’t live, or die, without. From cradle to grave, we are born to consume, and if you aren’t able to outrun the creditors in death, then don’t worry, your next of kin can pick up the tab.

We die as we live, buried in debt.

But as with most of the ingenious advancements of capitalism, the practice of outsourcing our death, and having our dead bodies sold back to us, has only been with us for a relatively brief time.

Those who are familiar with popular YouTuber Caitlin Doughty, and especially her episode of The Midnight Gospel, are most likely aware of the modern funeral industry’s genesis in the American Civil War. Prior to the late 19th century, death and funerals were a community affair. When you died, your family would wash and dress your body, lay you out on a table in the home, and conduct a simple service before taking you outside and burying you beneath your favorite tree, or perhaps carrying your coffin to the local cemetery to inter you. But 600,000 deaths have a way of changing people (or used to anyway) and the men who died of war and disease far from home were a golden opportunity for the recently created profession of embalmers who performed their work on the battlefield and shipped the bodies back to the families.

Even still, embalming might have been relegated to a historical footnote if Abraham Lincoln didn’t take up the practice himself, but in 1862 he had the body of his son embalmed, and then famously was embalmed himself for the 180-city tour of his body from D.C. to Springfield, Illinois. Americans were fascinated, embalming increased in popularity, and along with it arose the concept of the professional funeral home.

Before long, as hospitals became more formalized and less people died in the home, death care became a professional service taken almost totally out of the hands of the people. Over the next century, certain myths would cement this idea in place. Myths such as the one about a dead body being too dangerous to handle without a professional certification, or the idea that decomposing bodies pose a public health risk to water sources, ideas that are patently false. Also bolstering and legitimizing embalming and hermetically sealed casketry was a growing Christian evangelical movement that frowned upon the idea of cremation and promoted burial as following in Jesus Christ’s example (with the added benefit of preserving the body for the Second Coming.) Incidentally, Jewish and Islamic religious law forbids embalming and call for immediate burial of the body.

In the 1960s, investigative journalist Jessica Mitford was already writing about the predatory practices of the funeral industry, which led to congressional hearings and eventually the FTC funeral rule to protect against abuse of the bereaved to a degree, but nevertheless, the cost to die has continued to climb upward. With everything that capitalism takes from our lives, is it so much to ask that our deaths be allowed to release us? Like so many other invented industries of the last century, why are so many convinced that we are stuck with burdening our families in $10k of debt just to lay our bodies to rest?

It’s true that beginning in around the 1950s cremation has grown in popularity. Today over half of Americans choose this option, with the prohibitive cost of burial being a driving factor. A direct cremation will cost only around $1,000 in most parts of the country, assuming you use no other services of the funeral home. However, living in the times that we do, when every ounce of Co2 released into the atmosphere pushes us closer to mass extinction, it may give some people pause to learn that cremation in the United States is responsible for 1.72 billion pounds of Co2 released annually.

And still the machine marches ever onward, consuming everything in its path and leaving nothing untouched. Over 600,000 members of our communities have died from Covid-19, and the number continues to rise, yet one of the most progressive pieces of legislation to be born out of this disaster is a bill to reimburse the funeral expenses that are largely unnecessary to begin with.

I often (every day) consider the psychological cost of the sanitization of death as well. Exorbitant prices aside, what was taken from us when we lost possession of our dead bodies? How is it that we’ve simultaneously become desensitized to horrific and preventable death while also taking on a fear and disgust of the dead bodies themselves? Whether it’s the climate or the pandemic, all signs point to the impending need for us all to process a lot more death than usual for the rest of our lives, so it’s worth asking if taking on an active role in the death care of the ones we love the most might change our relationship to all that death, and our own mortality, in any meaningful way.

I want to return to our thought experiment now and lay out a vision of a death untouched by profit motive. So, the cat tripped you and you died. Ah, shit. Someone who loves you finds your body, and assuming there’s nothing to be done at this point to save you, they call in all of your friends and family, and together they begin to mourn. There are no expectations of composure as the visceral reality that your life has ended begins to sink in. There are tears, of course. There is wailing. There are pots of coffee made and shots of whiskey poured. There are no limitations placed on the expression of grief. You are laid in your bed, while those closest to you spend time sitting next to what physically remains of you. They tenderly wash you, relishing in the last moments they have to study your face. You are dressed in your favorite t-shirt while they listen to the albums that you loved the most. (Joan Osborne’s triple platinum 1995 debut album “Relish” perhaps.) In the depths of their unfathomable sorrow, they take the first steps toward coming to terms with this new reality as they see and touch your dead body. While this is happening, your grave is being dug in the local, community cemetery. There won’t be a fee to place you here aside from perhaps a small donation to the caregivers of the land. You will be wrapped in a quilt that your grandmother made and placed beneath the soil where your body will begin to decompose. Worms, beetles, and various other insects will consume your flesh and turn it into soil. Within a year or so you will become a skeleton, but that too will eventually disappear, leaving behind trace minerals that over the course of millions of years will turn to stone.

For nearly all of human history, people have taken care of their own dead. The Civil War was a mass death event that revolutionized the death care industry for the worse, and as we live through another mass death event, and seemingly will face more in the future, it is my hope that we can revolutionize the care of our dead once again. Save your coins to pay Charon, friends, and bury your own.

Harvey Day is an amateur death historian who left a mortuary science education disillusioned with modern funerary practices. She is the co-host of Hoot n' Holler: A podcast about the Ozarks and a mutual aid organizer in her community. You can find her on Twitter @HarveytheHaint