The Hollow Relief of the Derek Chauvin Verdict

This is an exception—a self-serving, deliberate one—to the rule.

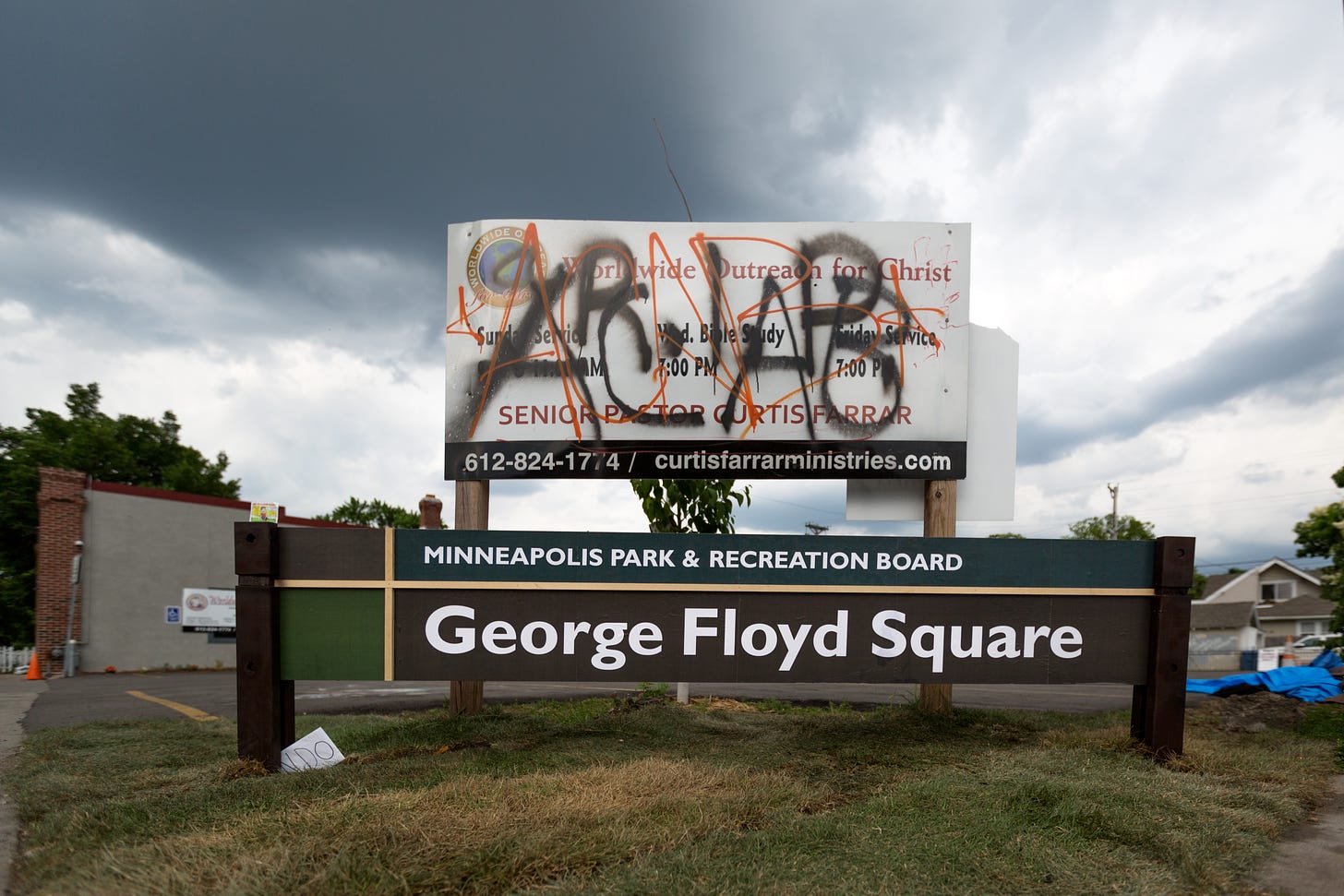

It's been an incredibly hard year for my beloved Twin Cities. The murder of George Floyd this past May turned Minneapolis (and to a perennially lesser degree, St. Paul) into the epicenter of a renewed fight for justice in the face of the profane and relentless violence committed against Black people by agents of the state. Between then and now, my community has burned and rebuilt, planned and fallen short. The Twin Cities have transformed into something bigger and more significant than they were a year ago. To the rest of the country, Minneapolis and St. Paul have become synonymous with America's failure — if not outright refusal — to address the latticework of injustices that empowered a white police officer to kneel on an unarmed Black man's neck for nearly 10 minutes, immune to his dying pleas, at an intersection now known widely as "George Floyd Square."

On Tuesday, a panel of Hennepin County jurors found former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin guilty on three counts of murder and manslaughter. The verdict was the culmination of weeks of wrenching, and frequently appalling testimony from attorneys, and experts, and ordinary passers-by who all described the same sense of powerlessness at being unable to stop what they all saw happen. It took the jury just 10 hours to declare Chauvin a murderer — a verdict that was met with cheers and weeping and spontaneous music from a community besieged by troops decked out in full combat gear. It was a moment of painful catharsis in a city that had become like a spring, dangerously compacted by an ersatz militarized occupation, laughably titled "Operation Safety Net," meant to tamp down on the roiling fury that occurs naturally under institutional systems of inequality and oppression.

The sense of relief that radiated out from the Hennepin County Courthouse when the verdict was announced was both palatable, and immediate. It pierced the heavy tension and foreboding that accompanied the rolling military convoys, and loitering police troopers who served as a constant reminder that not only were things reaching a breaking point, but that the state had already committed to being the ones to do the bulk of the breaking. The air had become thick with a sense that things could go very bad, very quickly, as politicians and police flexed their muscles in a mad scramble to avoid looking so helplessly out of their depth, as they had during last year's protests.

The message, previewed in part in by state's response to the protests in nearby Brooklyn Center for Daunte Wright, another unarmed Black man killed by a white cop, was deliberately unambiguous: "Don't fuck with us. Not now. Not ever."

And then came the verdict, and the celebrations, and the relief, and the feeling that something had been achieved, even if that "something" was unclear. As I write this on Tuesday evening, the police and the state troopers and the national guard are all still here. George Floyd is still gone. The same failings that lead to his death are still enshrined and protected by those with the power to make a difference.

There is relief over what could have been but wasn't, but relief is not enough.

Consider, for instance, the lengths to which prosecutors went to separate Chauvin from the otherwise supposedly virtuous body of the Minneapolis Police Department.

"You will learn that on May 25, 2020, Mr. Derek Chauvin betrayed this badge when he used excessive and unreasonable force upon the body of Mr. George Floyd," Special Prosecutor Jerry Blackwell told jurors during his opening statement.

"I vehemently disagree that that was the appropriate use of force for that situation," Minneapolis Police Chief Medaria Arradondo declared, in a transparent effort to negate Chauvin's argument that he was simply a good cop in a bad situation.

This "bad apple-ing" of Chauvin may have been effective at netting a conviction, but what kind of change does it actually represent? What good is excising a tumor from a body only after the inoperable cancer has spread? There's relief that a measure of accountability has been achieved in this one instance, sure, but what does that matter when it was attained by denying the reality of why it was necessary in the first place?

Already we're seeing how this might play out on the national stage. Politicians are suddenly feeling as if there's less pressure to move ahead on any sort of meaningful police reform, now that Chauvin has been convicted, and left the mythical proliferation of "good apples" to just try to do their job. But that's not progress. That's sacrificing a pawn to keep playing the same game as before. It's an excuse to ignore what could be, in the service of what already is.

I'm a white guy, and my sense of relief at the Chauvin verdict comes from a place of enormous privilege. I'm relieved that the man who murdered George Floyd is off the streets and no longer in a position to hurt anyone else. I'm relieved that more people weren't hurt by the massed police and military forces, tasked with preserving the sort of "order" that prevents real justice from taking root. I'm relieved that there are people in my community who have found a measure of solace from Tuesday's verdict.

But no matter how real my relief is, it's useless when the fact remains that what happened Tuesday was an exception — a self-serving, deliberate one — to the rule. For those here in Minneapolis, and around the country, who live under the ongoing consequences of that rule, people who don't have the protections my skin color affords me, relief is hardly a solution for the very real injustices that will exist tomorrow, regardless of whether Dereck Chauvin had been convicted or not.

The relief people are feeling across Minneapolis and St. Paul is real, and it's important. There is a sense of having avoided something much worse. But relief is not a victory. It's barely even a beginning.