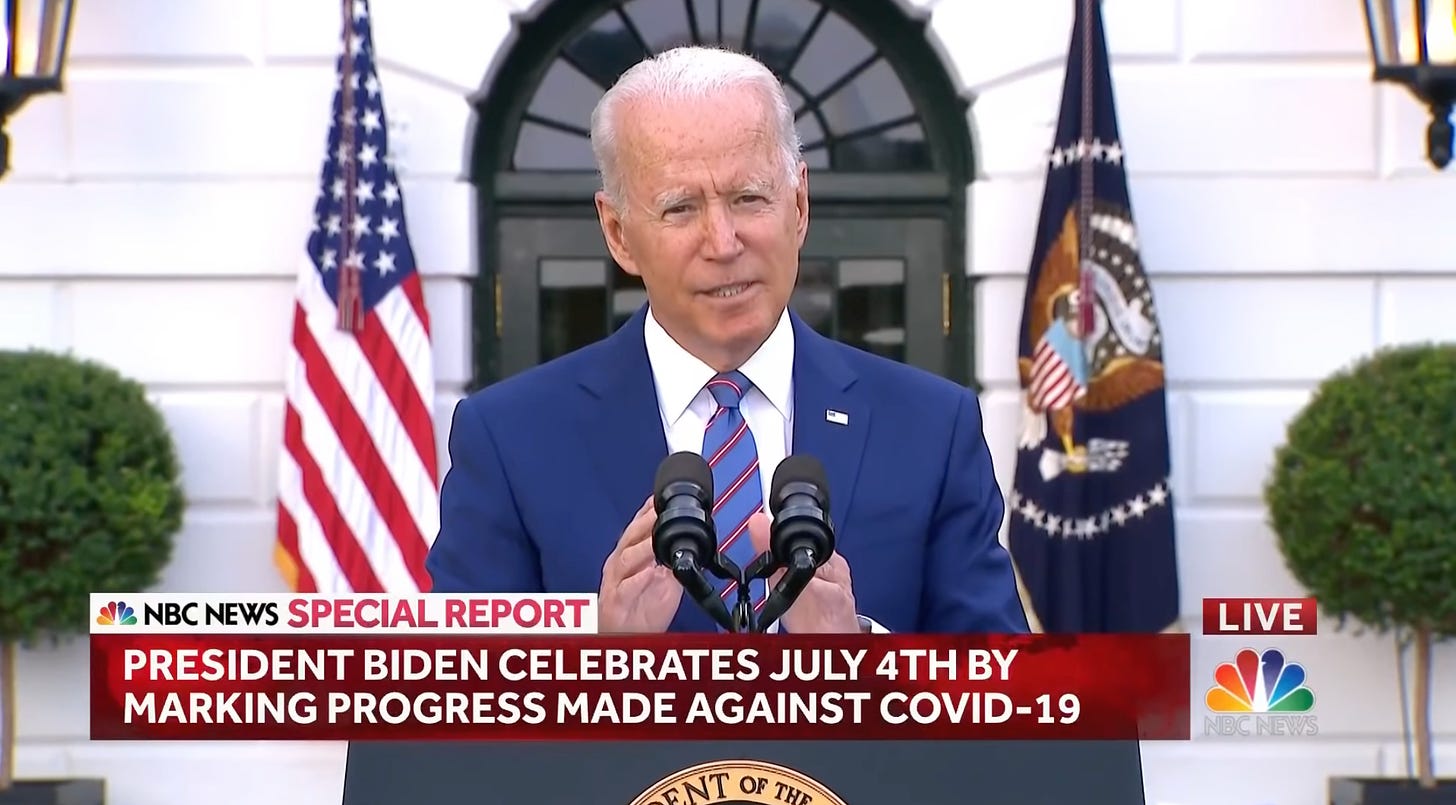

Ever since President Joe Biden announced that the U.S. was "closer than ever to declaring our independence from a deadly virus" on July 4, virtually everything has gone to hell.

The Delta variant, first detected in India's spring wave months prior, has resulted in a surge of coronavirus cases, hospitalizations, and death rivaling only those seen in the despair of last winter. The long-term efficacy of the vaccines has been called into question by the federal government's own confusing messaging about boosters and masking. And after more than a year and a half of the pandemic, national debates about long-settled questions like where unvaccinated people (like kids) need to wear a mask to mitigate the spread—not outside, definitely in schools—continue to dominate public discussion about the virus.

But Biden wasn't exactly wrong. Even as the guidance and recommendations change, all of the measures the government took at the beginning of the crisis—with the exception of distancing and masking, and even then only in some states—have been almost entirely dismissed in favor of a more uncaring approach. The government is done with COVID, even if COVID isn't done with us.

More and more kids are getting hospitalized with COVID than ever before, and in some states children's hospitals are already completely overwhelmed with cases. Earlier this month, there were 72,000 infections in a single week, according to data from the American Academy of Pediatrics. But there's been almost no conversation about shutting schools down again, because over the course of 17 months there's been no real concerted effort to help kids and their parents navigate online learning.

It took a huge public outcry and several days where the eviction moratorium had lapsed for the Biden administration to extend it earlier this month. Even then, the extension was—true to form for the Democrats—means-tested in the most convoluted and obnoxious way imaginable.

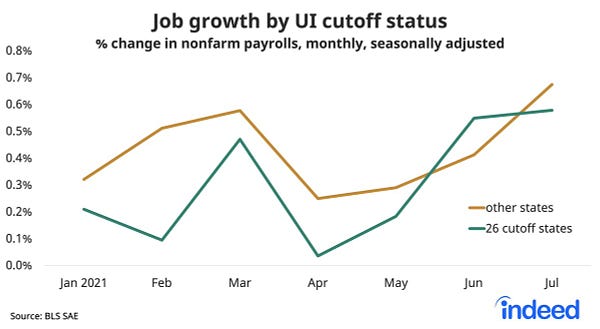

Maybe most damningly, there's been no push whatsoever to extend federal pandemic unemployment compensation (FPUC) benefits, which provide $300 per week to the unemployed on top of what they get from state unemployment, and are set to expire in September. When panic over "labor shortages" gripped the nation's impatient customers and KFC franchise owners earlier this summer, Republican governors seized the opportunity to unilaterally reject the extra money from the federal government earmarked for their workers.

One was Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, whose state has been a sea of red on the CDC's transmission map for weeks. DeSantis, like other governors around the country, argued that people didn't need to be on unemployment anymore and that ending the benefit would effectively push them back into the workforce. Instead, it had virtually no impact on jobs:

Where the cutoff did have an effect, though, was on incomes. A paper cited by the People's Policy Project last week found that in states where the benefits have already been ended—more than half of all states—net incomes plummeted by more than $264 a week. And yet on August 19, Labor Secretary Marty Walsh and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen sent a letter to Congress arguing that it was "appropriate" to let the benefits just end, unless, of course, the unemployed live in a state where the Delta variant is surging—i.e. all of them, but in particular, largely the ones that have already ended the benefit.

“We still have more work to do, but the trend is clear: thanks to the grit and ingenuity of the American people and with the federal government executing on a plan to bring our economy back, our nation is getting back to work,” Yellen and Walsh wrote. Meanwhile, this obsession with "grit and ingenuity" and "getting back to work" has made it tougher for people to get vaccinated, as the Washington Post reported last week:

About two out of ten unvaccinated employees said if their employer gave them paid time off they’d be more likely to get vaccinated, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation survey of 1,888 adults conducted from June 8 to June 21. Three vaccine clinic representatives said in interviews that the time-off issue was one of a handful they commonly hear from vaccine hesitant people.

That includes people like Zachary Livingston, the manager of a Subway in the Denver area.

The 40-year-old said he has been working 60-plus-hour weeks for months — with no bump in pay to his approximately $35,000-a-year salary — to cover gaps in the store’s schedule as it has struggled to find workers. He’d like to get vaccinated, and believes everyone should get the jab, but said he hasn’t had the time or mental space to do it.

“By the time I’m out of work, it’s time to go to bed,” he said.

At this point it's easy to forget that the first and only real shutdown of the pandemic actually worked. Outside of the areas where community transmission in America began, like the New York metro area and Washington state, there was a relatively sustained low number of cases until about late June 2020. Severe lockdowns like the ones we had at the start of the pandemic couldn't and probably shouldn't happen again, but there are parts of this strategy we could pull from, like paying people to stay home from work. Instead the government is yanking the floor out from under people at their most vulnerable moment, and just further complicating the obstacle course struggling people have to navigate in order to get help. Take this Florida woman's recent account in the Washington Post:

After she prepares her 7-year-old daughter for the school day, [Meli] Feliciano settles in around 8 a.m. for a round of calls and emails with potential employers, the property management company that liaises between her and her landlord, and hunting through a tangled, complex web for any aid that may help them get by. She posts frequently on local Facebook unemployment groups, offering her hard-won knowledge to people navigating the same system.

“I have to call about this application. I have to call about rental assistance. I have to get in touch with the landlord. I have to call and reschedule this bill and post it out further so I can juggle it,” she said. “It’s like playing chess, and I suck at playing chess.”

It couldn't be clearer that more intervention is needed from the government. Instead, the Biden administration has taken an approach to COVID which is unmistakably driven by politics, by the (not misplaced) fear that the pandemic continuing through next year's midterms will end the Democrats' congressional majority and further exacerbate the GOP and media focus on Democrats as a party of permanent lockdowns, even though we've never actually had one of those. Couple that response with Republican governors who are now outright anti-public health—as opposed to just gesturing meaninglessly toward it, does this remind you of anything—and it becomes more obvious that the coronavirus is something we're just going to have to live with for the foreseeable future. The new normal looks less like "American grit and ingenuity" and more like sacrificing ever-increasing numbers of people on the altar of Hard Work.