Discourses With: Lux Magazine's Cora Currier on Socialist Feminism

'We want the ability to learn to live a good life, and we want to be unapologetic in those demands.'

Feminism is broken — or, at least, the commodification of feminism is. The Netflix-glamorized mythos of the girlboss is dead after proving herself, time and time again, of being no more capable of feminism than the boy bosses who came before her. The widespread adoption of the label "feminist" by companies and celebrities has done more to elevate these individual brands than to materially elevate the women and nonbinary people who work for them.

Just as COVID has further amplified existing racial inequalities, the pandemic has simply pulled back the curtain on corporate feminism, revealing all the ways that it has not, in fact, improved working conditions for women, particularly parents. This basic truth — that corporate America will not save us, no matter how fat the benefits package — is just one of the many things espoused by the staff at Lux, a socialist feminism print and digital magazine that launched at the end of 2020.

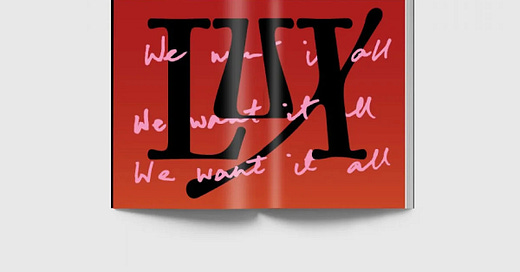

Named after socialist activist and thinker Rosa Luxemburg, the publication's "luxury"-adjacent name and tagline, "We want it all," acts as a challenge to the narrow capitalism-approved vision of "having it all" touted by traditional women's media. Last month, I spoke with Cora Currier, an editor at Lux, about the publication, socialist feminism, and the Lux staff mission to redefine the concept of luxury and what it means to live a good life in a world of austerity.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Can you tell me a bit about your work as it relates to socialist feminism?

I come from an investigative reporting background. I covered national security and surveillance. On the one hand, that means I was in a place where feminism is used and abused, like the CIA promoting Women's History Month by way of boosting [former Trump CIA Director] Gina Haspel’s nomination. Obviously, there's a million ways in the tech and surveillance world that we need feminism, and we need to look at the gendered ways that those issues come into play.

Back in 2011, around [the] Occupy protests, Sarah Leonard, one of my co-editors at Lux, and a couple of other folks who are part of our contributing editors and contributors to Lux, were part of a Capital reading group without men. Having had the experience of sitting in college seminars or activist spaces and having men lecture us about Marx, we decided we wanted that space for ourselves. And then we moved on to classics of the socialist feminist tradition. That’s how I came to the project, but Sarah, Marian Jones, and other editors were also involved in the NYC-DSA [socialist feminist working group], and other reading groups.

So when Sarah wanted to make Lux a reality, a lot of us were thrilled and ready. We felt like we had been developing this theology and had been wanting a publication like this for a long, long time. I want to bring that journalistic background to Lux as well. How do we look at issues that are not traditionally considered feminist issues … Housing, climate change, surveillance. How do we see gender and sexist oppression and barriers to liberation in those realms as well?

I feel a lot of people have similarly radicalizing experiences where they're like, “There's something definitely wrong about the way that feminism is being used in this particular context to advance one person or a certain ideal.” The very obvious example is the concept of the "girlboss." The problem is the way that feminism is applied to capitalism or other agendas that don’t help people on the margins. How is socialist feminism a response to that?

One definition of feminism that we've really made central to our analysis at Lux is bell hooks: that feminism is the struggle against sexist oppression. Feminism is something you do, it’s an organizing philosophy. It's not something you wear. It's not an orientation, it's not a book, an identity, a belief system. Of course there were earlier iterations of it in the ‘80s and ‘90s, of the female CEO, and Clinton and the model of the glass ceiling, etc, but I don't think it's a coincidence that the girlboss phenomenon really was pushed after the 2008 financial crisis, and that it grew up in that period of reckoning with what capitalism had wrought.

We were asked to believe that just promoting women into business, into leadership roles, was going to fix capitalism, or that it was going to fix long-standing inequities in society. Or that it's going to fix, for example, places where the state has shrunk back: that if women in CEO positions are going to promote better maternity leave policies, or childcare resources through their companies, that's meant to stand in for a lack of federally-guaranteed maternity and family leave or state-sponsored childcare, or any sort of universal program.

And of course what this ignores is the vast majority of people who do not work for those companies. It also just promotes an idea of individual success on the backs of the largely-female workforce that's paid very low wages to clean those offices and care for those children, so that certain ranks of women can enjoy what we've been told is freedom and success.

And feminism has been used to gloss capitalism in that way, and we've seen them fall. Sheryl Sandberg is now more associated with Cambridge Analytica and Facebook's data scandals and misinformation than she is with Lean In. We've seen exposes about The Wing’s treatment of its low-wage workers. We've seen totally bonkers stories like the implosion at Thinx, the period underwear company. And they've proved just as effective at underpaying and bullying their workers as their male counterparts. You also see this in the way that feminism is packaged and monetized on Instagram, by influencers, by celebrities. You see it in politics, obviously in the high-ranking political appointments, where we're supposed to just take it as a given that putting a woman in charge of drone strikes is going to make progress … I think that we've seen the abuse of feminism in that way. I don't think that campaign is working anymore. People don't want that anymore, and they're rightly suspicious of the feminism that's been sold to them.

So we want this magazine to be useful. We want to profile organizers, intellectuals, to offer models of how to live a political [life] and the movements we need to succeed. There are countless inspiring movements out there. You see it in workplace organizing, in groups like the National Domestic Workers Alliance, the reproductive justice movement which emerged to fill gaps [from within] the traditional abortion rights movement. So we have all these fantastic models and movements that we want to build on and to highlight, and talk about how we strengthen that and how we bring robust visions of the good life to the center.

Who has been left behind by this exploitation of what it means to be a feminist and what it means to thrive as a woman?

Low-wage workers across the spectrum, be they domestic workers, care workers, undocumented farmworkers, people in the backs of restaurants. Also, the people who are most likely to be sold this corporate version of feminism: the mobile millennial person who's supposed to create a brand for themselves and climb up this ladder. That person is also being left behind by this brand of feminism because the reality is that chances of their success in that realm are very slim and the structural factors — student debt, the pandemic, the economy — are all working against them. So even the people that this ideology is really aimed at are being left behind.

You have sectors like nursing, teaching, care work — work that's been traditionally feminized, traditionally thought of as women's work. And that feminization is used as justification to underpay, because it's supposed to be a labor of love and “women's work." Nurses as well — even if they're unionized, even if they might have higher education levels and status in society, they're still systematically undervalued and that devaluation is used to push austerity on them, is used to justify pay cuts. Pretty much everyone is left out of this vision except a very thin strata of people.

I am wondering if you might be able to take me through aspects of the history of American feminism where socialism has been erased. What are the histories of socialism within the women's movement that we're missing?

The Combahee River Collective, which Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor did a beautiful oral history of a couple of years ago called How We Get Free. They explicitly identified as socialist feminists and it was their statement that coined the term "identity politics." And that's a term now that gets widely used and abused and is often derided on the left as a distraction from class politics. But they saw identity as a way of drawing lines of solidarity between different forms of oppression, and as a very potent radicalizing force and as a form of solidarity, not for division. That's a legacy that is often forgotten, that that phrase itself came from socialist thinkers.

Another historical movement that has rippled through contemporary feminism is the work [that began with] Italian feminists in the ‘70s, the Wages for Housework Campaign, the popularity of which has trickled down through phrases like “emotional labor” and “care work.” [The campaigners] helped us to see that labor doesn't stop at the factory gates. Labor enters the home. Capitalism continues to order relations in the home. And that framework is also really useful in thinking about the ways that our home lives are arranged, the ways that gender plays out in our personal lives, and enables certain types of economic systems.

I'm generally really excited about these various new media projects including Lux, including what we're doing over at Discourse Blog, creating this departure from corporate media. So much of mainstream writing on, for example, the labor movement, unfairly portrays an equal power dynamic between workers and bosses, and makes workers seem like the antagonists that are hurting these poor bosses. Or especially in women’s media, mainstream publications allow someone to use the label of being a “feminist” to skirt criticism for their un-feminist actions. How do you feel Lux will fit into this media landscape?

We've got an explicitly political project with this magazine, which is bringing together socialism and feminism as two things that are often seen as at odds with one another, or viewed with skepticism by people in either camp. So we are looking to create stories that show the ties that bind.

The title is named for Luxemburg, but it is also a bit of a pun on the traditional women's luxury consumer goods magazine, and the idea that women's magazines have always been about selling you something, and we're selling you socialist feminism. We thought about how we could design something that was accessible and readable and we wanted it to be a print magazine for exactly that reason, that it might be something someone picked up by accident.

Yet we also didn't want to go too far in that direction and then fall into the same trap of selling feminism through artfully arranged quotes on Instagram. There are all kinds of entry points into left politics. Some people find it through a magazine and we want this magazine to be interesting and provocative for people who are already on the left, but we also want it to be a gateway for people who are curious and who are sort of sensing the growth and spread of socialist ideas in the U.S. and want to learn more.

Within traditional, corporate media, do you have hope that some of that change, such as when it comes to reporting on systems of power and capitalism, might come from the inside instead of just from challengers?

As socialist ideas and policies gain traction through the efforts of organizers and politicians — we've certainly seen that over the last several years, beginning with the Bernie campaign, around the growth of DSA, around even going back to Occupy — at a certain point it becomes harder and harder to ignore them and still do your job as a mainstream journalist.

Secondly, media is in turmoil. You have an industry that's in constant peril and constantly trying to figure out what the model is that will save it. At the same time, you have a growth in organizing among journalists. And that's definitely created a shift in consciousness among a whole generation of writers and editors and workers who had previously been told that they should just work for little or no pay and build their brands and [be grateful] for whatever job they could get.

Was there anything else that you wanted to mention, or anything that people should know about Lux or socialist feminism?

The pursuit of the good life is a really important aspect of what we're trying to do for this magazine. It's about redefining what luxury is. It's not consumer goods, environmentally destructive, outsourced to developing countries, type of consumer luxury. It's about: what does pleasure mean? What does luxury mean without exploitation, either of fellow humans or the environment?

We want to think about that pursuit of the good life, and we have a big focus on pleasure. We have this wonderful interview with one of our contributing editors, Ariella Thornhill, who's working on a sex ed book, and she's trying to think about all of the aspects of pleasure and all the structural barriers to pleasure. We have a little section of recommendations from our editors that are just like things that bring us joy.

Each issue is going to have something from the archive of feminist history. It might be something that's out of print or a newly translated piece. In this issue, we have an Italian manifesto from the 1970s from the women's struggle in Padua, Italy, and it's about abortion. But it says very bluntly and empathetically that the problem is not abortion — it's wage labor. It's a society that says how much money you make should determine how many children you have. It's the poor quality of contraception, which still is a constant topic in my group chats in 2021. It's about housing. The manifesto ends connecting the right to have children, [and] not, with the right to have good sex, and for that you generally want a place that's warm and comfortable. A room for yourself. And that means you need housing, and you need time, and you need to not be exhausted from work, or taking care of your children.

So that's what we're trying to recapture, is a feminist spirit that demands everything. And that's in our tagline, which is “We want it all,” which is again sort of subverting the girl boss idea of having it all, and saying, “No, no, we're really demanding at all.” Not just the right to abortion and pay equity — those are certainly important — but we want the ability to learn to live a good life, and we want to be unapologetic in those demands.

This blog is part of our interview series, Discourses. To read all of our interviews, click here.