The Bitter Struggle to Form America's Biggest Coffee Shop Union

Colectivo Coffee could become the largest unionized coffee shop in the country. Its owners are trying to stop that from happening.

Pandemics have a way of clarifying things—and last March, as businesses across the country closed because of COVID-19, it became clear to the employees of the Colectivo Coffee Roasters' Chain that their bosses might not do much to help them.

“There didn't seem to be a prioritization of our safety,” “KD,” a shift lead at a Colectivo cafe in Chicago, told Discourse Blog. (The Milwaukee-based chain has more than a dozen locations across Chicago, Milwaukee, and Madison, WI.)

KD (who requested that we use their initials instead of their full name), said that their store had increased its handwashing and sanitation procedures, but had made little effort to communicate with the staff beyond that. Instead, it felt like business as usual. In mid-March, as the reality of the pandemic set in, Colectivo began rolling out new menu items — a line of gluten-free baked goods, KD recalled.

“It was a lot to keep track of, to be coordinating this new menu rollout as the world was shutting down. And it just felt like we were being pushed to act as if everything was normal, as everything was very quickly falling apart,” KD said.

So the workers did what workers have done since time immemorial: they started to organize.

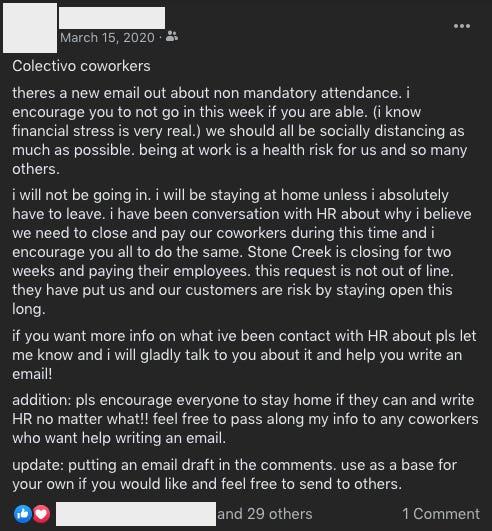

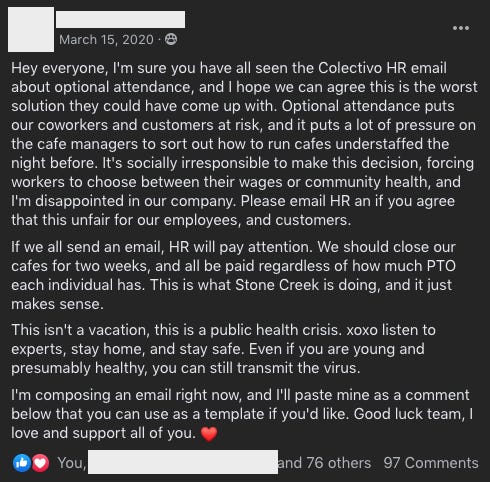

Another worker, a former shift lead in Milwaukee who wanted to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation, told Discourse Blog they had emailed Colectivo’s HR director at the time three days before hearing that a local competitor had shut down. Feeling upset and like the company had blown them off, they continued emailing HR, and texted their coworkers to join them. One of their colleagues wrote up her own email and shared it with a Colectivo Facebook group, which has a membership of hundreds of current and former employees. From there, an impromptu letter-writing campaign took off, demanding that all cafes close for two weeks with paid time off. One Colectivo employee also created a Change.org petition which borrowed language from the letters.

On March 16, the day after the letter-writing campaign began, Colectivo management yielded, announcing that it was shutting the cafes for two weeks and giving workers paid leave. It was not a complete victory — the company’s Milwaukee warehouse, which services all of its locations, stayed open, and workers were instead offered hazard pay for two weeks, according to former warehouse employee Robert Penner — but staffers saw clear evidence that organizing could get results.

That effort sparked a much bigger one: a push for a union. Some issues, like a lack of communication and delayed responses from management to complaints of unsafe working conditions, had existed long before the public health crisis.

“After [the campaign] worked, we were like, ‘Whoa, hang on,’” the former Milwaukee shift lead said. “Some people started jokingly talking about unions in the comments. And then next thing I know, [another coworker] was like, ‘I'm serious about this. And if you want to be on this, let's talk about it,’ and made a secret Facebook group and started adding people to get a feeling for it. And then once we found people who were about it, we made a new secret Facebook group to really get started on it.”

After meeting with a few union shops, the organizers chose to go with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers. IBEW wanted to go big. Instead of just unionizing one cafe or only the warehouse, IBEW set its sights on unionizing all eligible workers — including cafe staff, shift leads, trainers, workers at the warehouse and roasting facility, bakers at the Colectivo-owned Troubadour Bakery, and delivery drivers — about 300 to 350 people, according to Ryan Coffel, a shift lead and former general manager at one of the company’s Chicago locations.

On August 7, the union went public, calling itself the Colectivo Collective; organizing committee members included KD, Coffel, and Penner. On February 3 of this year, the IBEW Local Unions 494 and 1220 filed a petition for a representation election and, as part of the petition process, asked Colectivo for voluntary recognition as the union’s bargaining representatives. The following day, Colectivo’s Director of HR, LaShonda Hill, responded to the IBEW and denied its request for voluntary recognition, writing that “Colectivo Coffee will honor the results of a secret ballot election, only.”

A National Labor Relations Board-governed election began on March 9 and will end March 30; results will be announced on April 6.

Though some union drives at coffee shops, such as Spot Coffee, have succeeded, many coffee unions have failed to get off the ground, resulting in all baristas being fired. If they win, Colectivo would become the largest coffee company to unionize in the U.S.

The prospect is exciting for the workers, but they have encountered obstacle after obstacle. Since the union drive began, organizers say they have sat through misinformation-filled captive audience meetings and received coercive anti-union emails targeting workers on the organizing committee. More egregiously, some committee members fear that Colectivo is firing people or denying them opportunities in retaliation for their organizing. So far, the IBEW has filed seven unfair labor practice cases with the National Labor Relations Board on behalf of the workers, who say there may be more complaints to come.

These union-busting tactics are fairly common, but they might seem surprising to the average Colectivo customer. The company is known for its hip, colorful branding and seemingly liberal culture. In interviews with Discourse Blog, six current and former Colectivo workers on the organizing committee have described Colectivo as a company that portrays itself as providing a liberal, inclusive environment for its workers and customers, with an open-door policy for comments and concerns. But beyond that facade, they say, is an out-of-touch management that is doing whatever it takes to prevent its workers from unionizing.

“Every single [internal] email starts with how progressive the company is …The kind of vibe that I think many customers come away with is [that] this a fun and funky place. A lot of young and queer people work here,” KD said, noting that their store employs few BIPOC workers, and that that was on par with the speciality coffee industry as a whole. “Friends have said, ‘Oh, this looks like a fun and funky place owned by some Mexicans who really like Wisconsin.’ And I was like, matter of fact, that is not the case.”

Discourse Blog sent a series of specific questions to Colectivo Coffee about the allegations in this piece. Colectivo responded with a lengthy general statement that did not address any of the allegations. The statement read, in part, “we will be the first to acknowledge that we did not do everything perfectly - or even well - in the chaos of a global pandemic and parallel social justice movement.” Regarding the union drive, Colectivo wrote that it “turned to professionals who specialize in the law to ensure the company and its co-workers are fully informed … Colectivo would much rather be spending these funds on wages, equipment, tools and improvements to systems, but this wasn’t our choice.”

The relationship between Colectivo coworkers, as the company calls them, and management varied from person to person, but there were certain systemic concerns that workers had long before the union drive began. Staffers repeatedly told Discourse Blog about the poor communication between upper management and floor workers. Zoe Muellner, a member of the organizing committee and a former trainer in Chicago said management didn’t communicate with workers ahead of time about new policies or menu items, or about schedules, with some being posted late or changed even the night before. KD said management wouldn’t hear concerns brought up by workers, such as suggestions on efficiency and cultural sensitivity — for instance, the company’s use of the Mexican sugar skull on merchandise.

And both Muellner and the anonymous shift lead in Milwaukee shared concerns about management’s slow response to certain safety concerns at the cafes. In one instance, the shift lead said HR had taken weeks to ban a regular customer from their Milwaukee location in 2018 after he had come into the cafe wearing blackface. (HR later told the shift lead, who was present for part of the incident and who had asked HR and management to ban the customer, that they banned him after days, not weeks.)

Problems in the warehouse preceded the pandemic, too, and were part of the reason why the warehouse considered unionizing in the first place. Penner said that management had continually pushed back workers’ annual performance reviews, which are a part of the raise process. He also said that workers had a slew of other concerns about safety and equipment, which management also pushed off.

If these failings clashed with the company's lefty image, so too did its response to the union drive. Coffel and Muellner told Discourse Blog that any goodwill management may have had evaporated as soon as the union was announced. Immediately, Colectivo hired the Labor Relations Institute, one of the country’s biggest “union-avoidance” firms, to hold mandatory paid captive audience meetings, which require workers to attend to listen to the company’s opinions on unions in an attempt to dissuade unionizing.

According to U.S. Department of Labor agreement and activities reports filed by LRI and two consultants, Colectivo agreed to pay thousands of dollars for LRI’s services since September. The first filing from LRI stated Colectivo agreed to pay each consultant $375 per hour plus travel expenses. In two other activities reports, the two consultants, Pat O’Mara and Gus Flores, reported that Colectivo agreed to pay $187.50 per hour plus expenses, and $1,500 per day plus travel expenses, respectively. (This year, Flores also reported a compensation agreement for work performed since October for Tate’s Wholesale LCC, a Southampton, New York, bakeshop where management was reported on March 10 to have threatened undocumented workers with deportation if they were to join the union.)

At the captive audience meetings, LRI consultants shared misinformation and anti-union talking points, such as saying that a signed authorization card was legally binding, according to Coffel, KD, and Patrick Zastrow, a cafe coworker in Milwaukee who is also a union organizer. They also had workers watch an informational video about the voting process, which implied that the union would steal someone’s ballot if it wasn’t mailed by the employee themselves.

According to union organizers, there were two rounds of in-person captive audience meetings. One was in the fall, and the second was across February and March, after the organizing committee filed its petition with the NLRB for an election. Zastrow recounted one captive audience meeting during which the LRI consultant and the owners were combative in response to his questioning of anti-union talking points, and tried to cut him off while he was speaking. At a meeting in Chicago, Muellner said they were reprimanded for referring to the LRI as “union busters,” and told that the term was offensive.

For the second round of captive audience meetings, workers who identified themselves as organizing committee members when the union went public last summer were told they weren’t allowed to attend, because Colectivo already knew their position, Coffel said. As these meetings were paid, Coffel said he continually pushed HR for the committee members to be given a meeting of their own. Colectivo relented and held a meeting with the committee members, but according to Coffel and KD, the meeting was on video, was 45 minutes shorter than the in-person meetings, and was only with the LRI consultant and the CEO Dan Hurdle. Unlike in earlier meetings, the owners didn’t show.

Outside of these captive audience meetings, Colectivo’s owners have encouraged one-on-one meetings, and have hosted non-mandatory meetings in Chicago and Wisconsin, with at least one “Coffee with the Owners” event in Milwaukee. The event started with a coffee tasting and ended with owners giving speeches to ask workers to vote against the union, according to Zastrow, who hadn’t attended the event but heard from colleagues who did. (This is a common tactic: recently, for instance, Vice reported that Medium CEO Ev Williams held “coffee chats” with workers where he insinuated that a Medium union would cause the company’s funding to dry up; the workers’ union drive ultimately failed.)

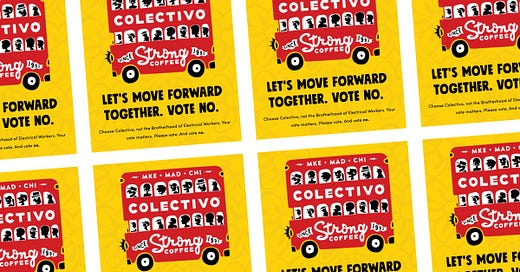

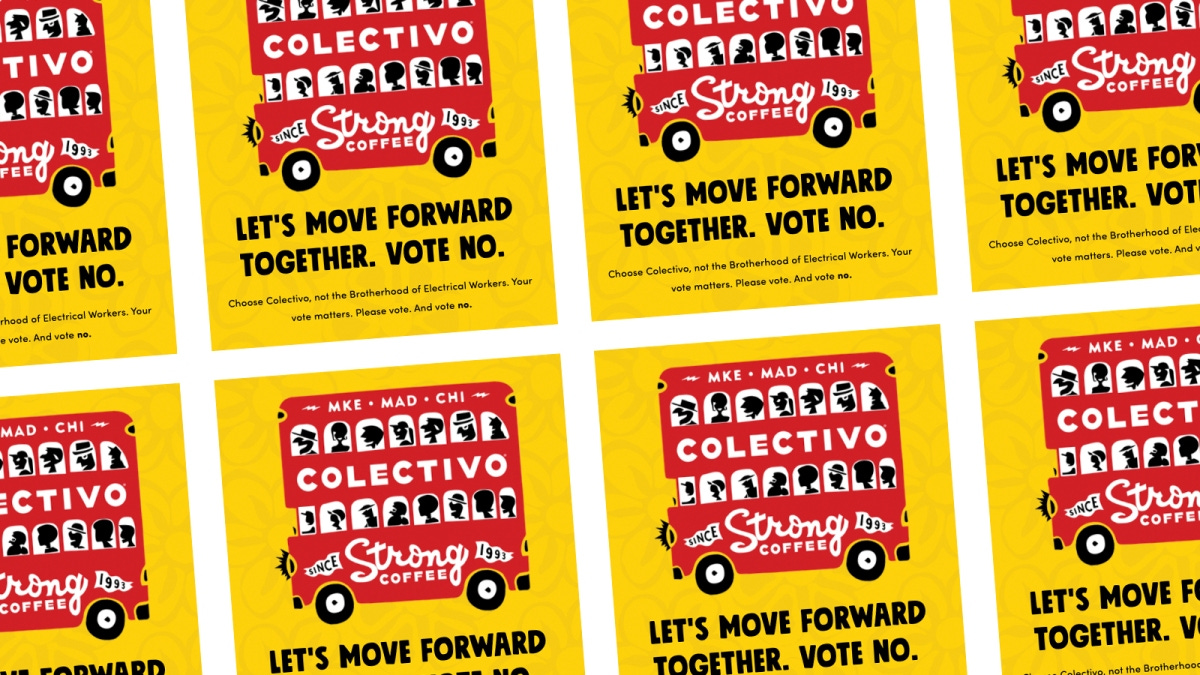

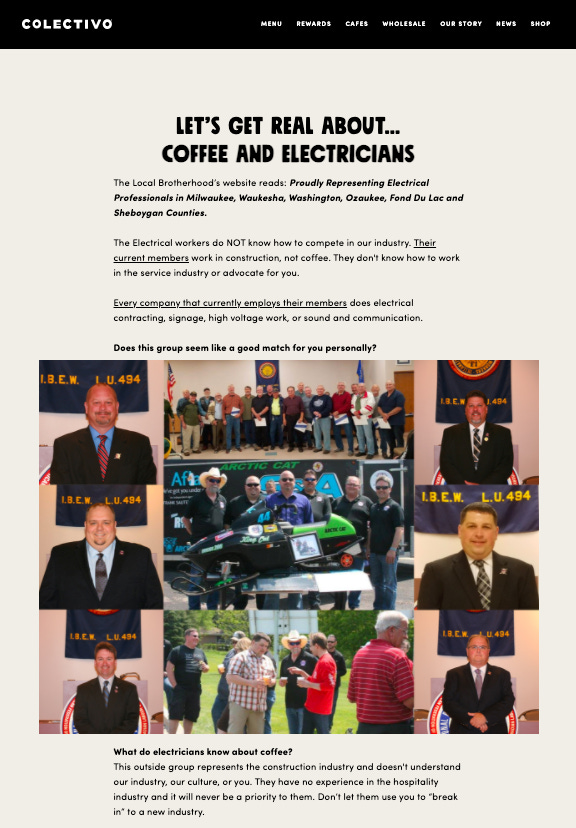

The union-busting has also seeped into their workplaces and in their inboxes, organizers say. Around the cafes, workers have seen a steady stream of posters rotate through the break room that they’ve referred to as the “Did you know?” posters, which contain exaggerated information about the IBEW or about “worst case scenarios'' of unionizing. Over email, workers have received personalized messages from upper management and owners asking them to vote against the union, and have been sent multiple emails with talking points that have questioned what electricians know about coffee, have accused the IBEW of trying to circumvent the will of the coworkers by asking for voluntary recognition as part of the legal unionization voting process, and have warned that voting for a union will only help the IBEW line its pockets. All of these messages are available on Colectivo’s website at the links above.

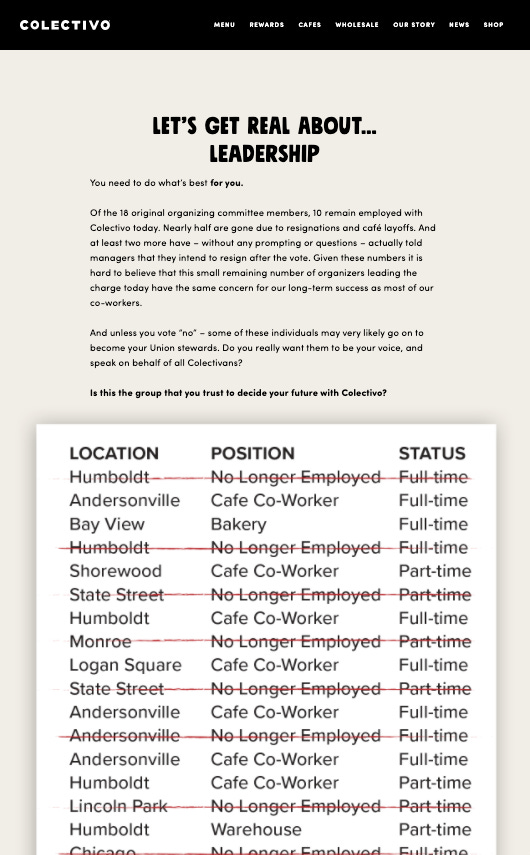

The most egregious email included an image of a list of coworkers who’ve been laid off or left Colectivo, some because of pandemic-related concerns, with the descriptions of those people crossed out in red ink. “Given these numbers it is hard to believe that this small remaining number of organizers leading the charge today have the same concern for our long-term success as most of our co-workers,” the email reads. The list of employees included those who had originally gone public with the organizing committee, but the list excluded their names, identifying them by location, position, and part or full-time status.

Coffel said the union isn’t deterred. Online, organizers have worked to debunk the company’s claims in videos or graphics posted to the Colectivo Collective’s Instagram and Facebook pages, or website.

Additionally, members of the organizing committee said they were suspicious that select firings and terminations were happening in response to the unionizing effort. During an extended furlough after the initial two-week shutdown, Muellner was brought back to work in the cafes around the end of May, and eventually went back to training full time. But in October, their position was “terminated” after working with the company for over two years. Muellner asked management if they could take a demotion to continue working in the cafes, but was told nothing was available, and that management would put them on a list to be contacted if any positions opened up.

During the furlough, the shift lead in Milwaukee also tried to go back to work after not being called back for months. They were willing to take a demotion and a $2 pay cut to be transferred to a store further away from home, just to be able to work one or two days a week. But they said that when the cafe manager at that location reached out to HR to make the transfer happen, it was shut down. Months later, the shift lead — who had been a member of the organizing committee for a time before stepping back — received an email saying their employment at Colectivo was officially terminated.

It’s unclear if workers outside of the organizing group had similar experiences before being fired. The Milwaukee shift lead said they weren’t sure if workers outside of the union organizers had also tried to stay employed by taking a demotion, but they said Colectivo had asked other coworkers to adjust their schedule or pay since the pandemic began, but that people scheduled for shift lead shifts were still paid shift lead wages. Similarly, Coffel said that Colectivo had asked workers to open their availability or take a demotion around December and January, “when it’s historically slow in the coffee business,” but he didn’t think anyone had actually been demoted. Both Coffel and Muellner said they weren’t aware of anyone else outside of the union experiencing situations similar to those of Muellner, Penner, or the shift lead, however.

This spring, Colectivo began advertising that they were hiring. After applying for another job with Colectivo earlier this month, Muellner said they still haven’t been contacted about a position. When Muellner’s trainer position was first terminated, the IBEW filed an unfair labor practice case with the National Labor Relations Board on Muellner’s behalf, but it was dismissed since Colectivo said the terminations were “due to COVID.” Muellner is still a member of the organizing committee, and was able to be hired on part time by the IBEW so they could keep working on the campaign.

“It does make it seem like them eliminating my position ‘due to COVID’ — at that point, if you were hiring again, and me having the skills of a trainer and knowing pretty much all of the standards for all of the beverages, it seems like it would be a no-brainer to bring me back, because I would need no training,” Muellner said. “With them kind of pulling these moves, I don’t know what will happen with [my NLRB complaint].”

Penner, the warehouse worker, had also identified himself as a member of the organizing committee when the union went public in August. After taking the furlough in March and needing to go back to work, Penner contacted his manager in July about coming back, then checked in several times after. In September, his manager called him back into work, and asked him to come in on a Monday. However, Penner said that a few days before returning, he was called by Colectivo’s COO Leo Lettow, who told him that his manager had “overstepped” and that he was no longer invited back to work. When he asked if he was being fired, he was told he wasn’t. Two weeks later, Penner’s position was terminated permanently.

But his attachment to the union continued to follow him. After that, Penner took a part-time janitorial job (Penner didn’t want to disclose the name of the establishment for fear of retribution). A few weeks in, he was told by his manager, who is a friend of his, that the owner had been contacted by someone at Colectivo, who had seen Penner working. The person allegedly called Penner a “radical labor organizer,” and that he was a “threat to [their] business.” The manager told Penner that he could keep him on for a bit longer and change Penner's schedule to avoid future run-ins with people from Colectivo, but that Penner would have to stop working there. Penner, not wanting to jeopardize his friend’s employment, left the position. (In a separate interview with Discourse Blog, Penner's friend confirmed the details of their conversation. Penner has also detailed his account of this in a video on the Colectivo Collective’s Facebook page.)

Other attempts at organizing during the pandemic have also proved effective. Zastrow, the Milwaukee cafe coworker, told Discourse Blog that the staff at his cafe signed and sent petitions to Colectivo in the fall and again in January when the store was rumored to be expanding to in-person dining. The first time management didn’t end up expanding dine-in, and the second time, after their petition, dine-in was delayed by two weeks. Management also went through a list of concerns and solutions that the staff had put together, and adopted some of their proposed solutions when dine-in returned, Zastrow said.

And during the uprisings against racist policing last summer, workers demanded that Colectivo do something to support the Black Lives Matter movement after the company had posted a black square image to social media and made their Ethiopian coffee the coffee of the week. In response, Colectivo launched a “Unity” coffee campaign that raised $43,000 for local NAACP chapters.

“I think that they're very careful. I think that they present [Colectivo] being comfortable and eclectic and worldly and progressive, but also without stepping on people's toes who might not agree because they don't want to lose that customer base,” Muellner said. Speaking about the Unity coffee campaign, they said the campaign was played safe, too. “It felt like if you were somebody who wanted them to say 'Black lives matter,' it was close enough. And it felt like if you were somebody who wanted them to say 'all lives matter,' it was close enough. It was toeing both camps enough because they don't want to alienate anybody, even if it might be the right thing to do.”

For now, the work continues. Coffel told Discourse Blog that another loudly pro-union, longtime employee who worked at the bakery had been fired last week, and that while he wasn’t sure what the person was fired for, he said the IBEW is planning to file another unfair labor practice case. “It kind of has everyone on edge,” he wrote via text, referring to workers outside of the union. But organizers don’t seem dissuaded.

“We're in this moment where I'm seeing a lot of energy, especially in restaurants and food service, towards unionizing and collective actions. I think the pandemic obviously brought a lot of that on because it put us in a really difficult spot universally, and also didn't allow anyone to quit their job to find a better one, because there were none. It forced a lot of people to dig in and really make the improvements of this industry as needed,” KD said. “I hope that more restaurants are encouraged to organize and people are able to get in touch with labor activists who can help them exercise their rights at work, because these are our rights. And we have every right to be doing this right now. So I hope that as we have been inspired by previous campaigns, we can inspire future campaigns and we can raise the bar a little bit, altogether.”

Disclosure: almost all Discourse Blog staffers are members of the Writers Guild of America East union.

Paul Blest contributed reporting to this article.

Update: One of the sources in this article reached out to us to ask if they could be identified by their initials rather than their full name. We agreed to this change and have updated the article.