Clubhouse Is Loud, Incoherent, and Packed With Suckers

Discourse Blog has partnered with our friends at Defector to bring you a taste of their work. If you like this post—which, duh, it’s good—we encourage you to check out Defector and subscribe!

This piece was originally published on Defector on April 22, 2021.

by Patrick Redford for Defector

I am in an audio chatroom called “🤩 PR & MEDIA SECRETS: Elevate your business and brand 💡” and learning the promised secrets, which largely consist of various tips for tricking journalists into writing about you or your venture. “There are endless amounts of ways of getting to these people,” one panelist says, suggesting $10 gift cards, before another emphasizes the importance of spelling everything correctly in pitch emails.

I hop into a room about bitcoin, as a speaker concludes a spiel for hundreds of laser-eyed true believers with, “Long-term thinkers win, and I think bitcoin is the ultimate manifestation of that. I gotta go. Bullish as fuck.”

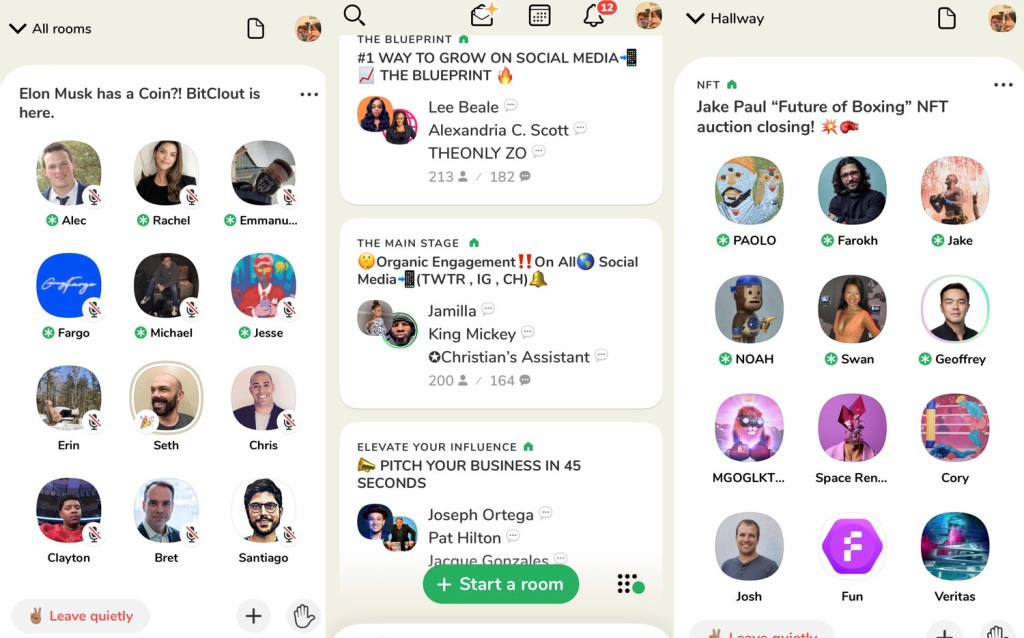

I join a non-fungible token auction with someone from the British EDM duo Disclosure, who is talking about which auction platforms accept the most forms of cryptocurrency. “How to Run & Scale Multiple Businesses” is a thin cover for a room devoted to Elon Musk, who, per a moderator, “has more demands on his time than anyone, out of all the people on the planet.” I am one of more than 2,000 people listening in on YouTube star and fake boxer Jake Paul speak in “Jake Paul ‘Future of Boxing’ NFT Auction Closing! 💥🥊” and say, “I’m excited to keep collecting, ’cause I wanna have my own digital art museum in the metaverse.”

I did not get my Clubhouse invite in time to hear a wealthy Miami-based venture capitalist declare “VC lives matter,” in a room stocked with zealous tech barons who do not live in San Francisco discussing how to destroy San Francisco’s reformist district attorney Chesa Boudin. A long monologue from a self-avowed reformed cheater in “All men cheat! I said what I said” is briefly derailed by a long tangent about the necessity of paying a cleaning service to do your chores so both parties still have the energy “to fuck [each other’s] brains out.” A different NFT chat has broken out into a serious argument; I join as one man winds to a conclusion about NFT evangelists’ disdain for working people (defined here as “regular fucking people buying lottery tickets—here on the East Coast we got Wawa”). He tells the host, “You’re talking like you’re God, who the fuck are you?”

This is all taking place on Clubhouse, a relatively new app that explicitly seeks to do to podcasts what Twitter did to the blog, what TikTok did to videos, or what Instagram Stories did to photo sharing: break down icebergs of internet into discrete little cubes, smaller and more digestible than their now-disrupted counterparts. In the words of one of its VC backers, “Clubhouse is about a real-time exchange of ideas, not just consuming highly-edited, static content. It’s a fresh experience that brings humanity and context to online social engagement.”

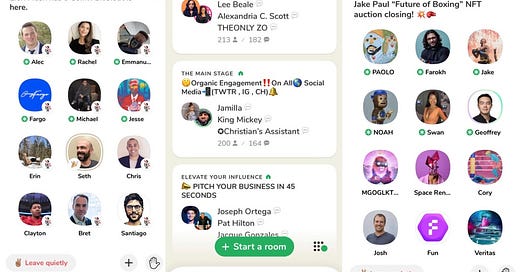

In practice, it means that the Clubhouse app is full of rooms with several hosts or panelists discussing a given topic, while the majority of the room is populated by silent listeners who can raise a hand to speak up if they want to talk. It’s structured like a conference hall, with hundreds of tenuously connected breakout rooms. Clubhouse is not open to the “general population” at the moment: You must be invited in by another user, which is a marketing tactic that’s succeeded in manufacturing an aura of exclusivity to the whole thing despite now boasting almost 10 million users and raising the company’s valuation to $4 billion. You’re not just listening to some British guy talk about how to grow your brand on Clubhouse by getting followers on Clubhouse. You’re listening to some British guy talk about how to grow your brand on Clubhouse by getting followers on Clubhouse before everyone else has the chance to do so.

Look at Clubhouse through the tech world’s lens, where every inconvenience is a problem to be thinkovated away for billions of dollars, and every pre-21st century invention is an obsolescent relic waiting to be disrupted. Through this myopic view, the app is a necessary, even inevitable, corrective to analog audio services that don’t offer Clubhouse’s level of interactivity. Podcasts, per Clubhouse’s logic, are rickety zeppelins waiting to be replaced. No other big-time social media network is driven by live audio, therefore they have a niche. Why would tech behemoths be scrambling to copy the format if it wasn’t a worthy idea?

Consider the app skeptically, however, and it’s tricky to determine what differentiates Clubhouse from, for instance, the very old and very popular existing networks of talk radio call-in shows. The pablum you’ll find on Clubhouse is only functionally distinct from some morning-zoo horror called Chad & The Slimer, because it is not available to everyone. It’s on your iPhone, and it’s backed by Andreessen Horowitz (known as A16Z), one of the most powerful venture capital firms in Silicon Valley.

We are now a full decade removed from Big Tech being able to convince anyone but the most glassy-eyed futurist that lofty sloganeering about making the world a better place is anything more than marketing. Airbnb doesn’t need to convince investors, shareholders, or the public that its platform enables you to “belong anywhere”; it only needs to show capability as a business and work as a service. The idea that humongous tech companies exist to furnish novel solutions to everyday problems only holds up if you consider “I can’t gamble on the stock market while sitting on the toilet” or “It is not easy to find videos of dogs performing mischievous acts” to be actual problems. Chalking up Silicon Valley’s trillions of dollars to “They just put stuff on your phone” is overly simple, if not altogether incorrect: The industry is building out the architecture for the digital-prime world.

Virtually every major American software creation emerges from the enormous concentration of wealth and power in Silicon Valley. While Clubhouse is no different—its founders both graduated from Stanford and worked for Google—it does stand out as a particularly emblematic product of its environment because the Venn diagram of the people backing Clubhouse and the topics discussed on Clubhouse is uncannily circular. This makes some sense, since the inconvenience it seeks to alleviate, if you can squint hard enough to see it, has already been alleviated. Clubhouse is an iteration on an existing form, in the same mode of any social media app. There is no nefarious Zuckerbergian myth or skeevy Snapchattian lust behind the app’s genesis. The founders just wanted to build a company that made money. The functionality of the tool is almost beside the point, since it’s not really all that fresh a concept. What is interesting is the tightness of the closed loop.

I have been been on Clubhouse for about two months now, most of which I have spent trying to listen in on whatever handful of shows are most popular whenever I log on. I haven’t followed anyone so as to keep a cleaner algorithm, and while my algorithm is still probably an imprecise representation of the app as a whole, the prevalence of dumb-guy business tactics, incomprehensible chatter about the speculative asset crazes of the day, and inane advice about how to become a social media influencer is staggering (I am also far from the only observer to note this). “Obviously we don’t want what happened previously to come back,” a panelist in “WILL DOGECOIN REACH $1?!?” is telling his nervous flock, “with respect to the Great Depression and what have you.”

Most of it circles back to advice on how to get rich. One form this takes is notable Clubhouse accounts, talking on Clubhouse about how to get more followers, again, on Clubhouse. The logic goes that Clubhouse is a new frontier for a hypothetical new brand of audio influencer, and since the app has yet to be truly colonized, there’s a frenzy to meet a hypothetical demand. It’s free real estate. What will you talk about once you follow everyone’s advice and gain a following? Who knows, but you can start with advising people how to grow their own brands.

The gold rush feels nakedly cynical and empty of actual substance. All social media platforms incentivize users to hustle and stake out a position of influence. It’s just that Clubhouse’s competition has been around long enough that there’s a veneer of substance. Public-facing accounts on Twitter and Instagram seek to offer snappy takes and cool pics, respectively, and though those offerings have been around long enough that we’ve imbued them with a value, they only differ from the crypto-evangelism and circular influencer babble in form, not function. After some initial revulsion to the naked ambition of Clubhouse’s more MLM-adjacent accounts, I realized that what they’re doing isn’t too different from my own attempts to grow my social media footprint. In Clubhouse’s case, the feedback loop is simpler and the language of growth is one degree less abstracted. But the only distinction between Clubhouse and its competitors is that Clubhouse’s novelty lays bare the hollow incentive structure that exists across social media generally.

Six of the 14 most popular accounts on Clubhouse are either Clubhouse employees or investors in Clubhouse, and the rest of the top 50 is replete with various VCs and investors. Over half of Clubhouse users follow one of the two founders, since he’s one of the many accounts you’re prompted to follow when you first open the app. Clubhouse first made waves last summer—at a time when virtually all of its 1,500-strong user base worked in Silicon Valley—for an incident when a posse of VCs and tech world luminaries got together to gripe about how press coverage of the tech world is inherently Orwellian, because, in the words of one exec, private companies should necessarily be exempt from public scrutiny via the press.

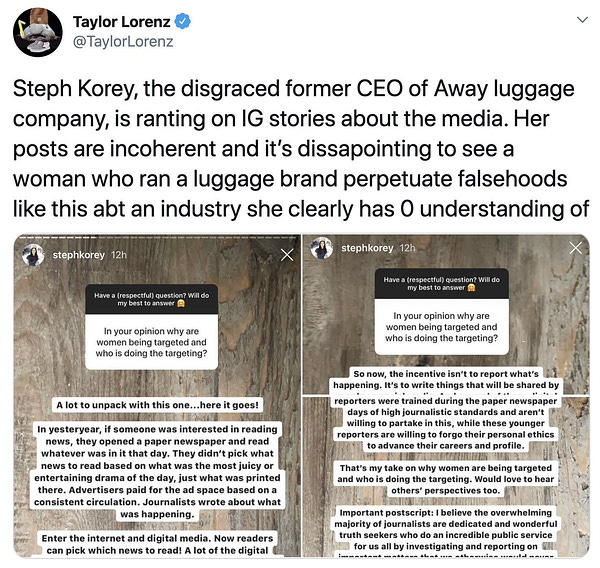

Higher-ups at Andreessen Horowitz, founders and CEOs of tech companies, and, most vocally, consistently incorrect tech evangelist Balaji Srinivasan gathered last July to talk shit about New York Times reporter Taylor Lorenz for her coverage of Clubhouse and her mild critiques of the disgraced CEO of Away. The group seemed to believe that the tech media’s heinous sin was, uh, covering the tech industry. (Lorenz later apologized after she incorrectly identified A16Z founder Marc Andreessen as the person who said a slur in a Clubhouse room, an incident which spawned a month-long harassment cycle led by outrage manufactory Tucker Carlson, various tech barons, and Glenn Greenwald, a journalist who took issue with Lorenz’s “tattletale, speech-policing ‘journalism,'” which is an odd euphemism for “reporting.”)

Last summer, Silicon Valley’s contempt for a press invested in anything less than full-out cheerleading ran up against the theoretical mission of Clubhouse, as a social platform that can scale to the masses will inherently need to be open, one where reporters can listen in on any conversation the same way any user can. Listening to what people say is sort of Clubhouse’s whole thing, after all, and there’s a contradiction in the fury against Lorenz for using the app for its express purpose. This wouldn’t have been a problem if Clubhouse had a user base that wasn’t so steeped in Silicon Valley’s techno-libertarianism. While the percentage of Patagonia-clad nouveau riche populating the app has been diluted by its growth, and while black creatives have helped push the app’s popularity out of exclusive Silicon Valley circles, you will not really be able to see all that much improvement when checking out what is popular.

Clubhouse’s next challenge will be to grow from a service tailored to a narrow band of consumers to a communication network with something for everyone. Users will branch off to fill their own niches and, at some point, the app will take on a different shape as it grows. Like Instagram evolving through the years from a place to post faux daguerreotypes to a bustling meme-theft bazaar, iteration necessarily defines the life cycle of social media, since users create the stuff other users log in for. Clubhouse’s user base has grown explosively since December 2020, growing from 600,000 to 10 million users. As that number continues to tick up, the concentration of Silicon Valley types will necessarily decrease. However, the app’s goal to grow into a place for more people with a wider array of interests than cryptocurrency is necessarily in tension with what Clubhouse is now. Marc Andreessen might know a lot about investing, but also, that material gets dry quickly, and users presumably want more out of their Clubhouse experience than Business Mindset all the time. This tension cannot be resolved by Clubhouse’s most popular accounts, though they are using most of the oxygen in the room.

I can’t really pretend to know whether Clubhouse will blow up and become the next Snapchat. No competitor has reached this size through live shows alone. What I do know is that while Clubhouse has clearly resonated with some people, I find it wholly repellent. The app’s preferred topic areas are one thing, but the unproduced, live audio experience as a format is hostile to attempts to grok a holistic understanding of the topic at hand. You won’t get much out of any session if you wander into it late. There’s also the fact the rooms are extremely difficult to moderate, as evidenced by the harassment of black doctors attempting to push back against anti-vaxxers. The Clubhouse listening experience is anti-context, tumbling past you in all directions rather than flowing along a planned course.

This is not to say Clubhouse has been as wretched for everyone, or that the format presents no possibilities. Even I cannot argue that it’s not stimulating. The “have you ever met a deer? how’d it go” room was a delight. An acquaintance mentioned how much he enjoyed a room hosted by Serena Williams and Alexis Ohanian about competitiveness. The “Whale Moan Room,” which is exactly what it sounds like, briefly provided a joyful absurdist rejoinder to the business tedium, until it was inevitably colonized and ruined by influencer types.

And then there’s China. In early February, thousands of Chinese users flocked to Clubhouse after Elon Musk joined the platform and used their brief window before censors shut down to the app to hold candid and often heartbreaking discussions about the state’s repression of Uyghur Muslims in the country’s northwestern Xinjiang province. Uyghurs living in China reportedly detailed their persecution. Han Chinese citizens expressed guilt and confusion. Everyone involved made connections they otherwise would have been unable to make.

“I was shocked. I had always thought they would never understand what we were going through or felt guilty,” one Uyghur participant told Vice. “It was really moving when they showed their emotions. It felt like the distance between us was not that great.” The outpouring of impermissible feelings that took place on Clubhouse probably couldn’t have happened in many other digital spaces, though this certainly has less to do with Clubhouse’s unique potential than the simple fact that it hadn’t been around long enough to be banned.

It is no coincidence that Clubhouse has taken off amid a pandemic, where talking to strangers is a treasured commodity. Will the prospect of remote communication be as appetizing in the forthcoming world where everyone can once again go outside and meet people with impunity? According to a handful of recent reports, user growth has started to tail off. I could see how Clubhouse would be a fun place to bullshit with your pals—it was when I lurked in a room called “we’re in a car rn” (they were)—rather than engage with popular rooms, but the idea of further screen-only interaction with my friends and loved ones after a year overstuffed with them makes me want to toss my phone into the Pacific Ocean.

That specific revulsion gets to the heart of my real distaste for Clubhouse: It sits squarely in an uncanny valley. Yakking or listening on the app more closely resembles meatspace human communication, which is not something I want disrupted by any technology more sophisticated than what Alexander Graham Bell created in 1876. That’s probably giving too much credit to Clubhouse, which is simply not an inviting enough space to rise from “off-putting” to “scary.” The world Clubhouse’s founders created is impressively trivial, and doesn’t seem enticing enough to really change anything. Maybe its potential takeover would be more alarming if its users were after actually fungible tokens.