The U.S. Establishment Needs a Better Answer Than Intervention

The U.S. has been intervening in Haiti for centuries, to ruinous effect. Something has to change.

In the early hours of Wednesday morning, a group of armed gunmen shot and killed Haitian President Jovenel Moïse in his home. Moïse was a deeply unpopular dictator who had spent years dissolving any semblance of democratic process in his country, and the details of his death are chaotic and muddled, allegedly involving Colombian mercenaries and two U.S. citizens of Haitian descent who were reportedly under the employment of a doctor with ties to Florida who was attempting to usurp the presidency.

Moïse's death leaves behind a power vacuum, as a legion of analysts were quick to point out, that is currently being filled by "Interim Prime Minister" Claude Joseph, who has quickly taken command of the U.S. and U.N.-funded military and police forces and established de facto martial law despite having an unclear mandate to the role of Prime Minister in the first place. The political situation in Haiti is complicated and unclear enough that even major publications like the New York Times and Washington Post are having difficulties distilling it into a coherent narrative for their audiences. But what other barometers of the status quo are clear on is the solution: military intervention.

On Wednesday, just hours after Moïse was shot, the Washington Post editorial board proclaimed that "Haiti needs swift and muscular international intervention," calling for a similar UN peacekeeping mission to the 13-year occupation that began in 2004. (That occupation followed the invasion of Haiti by U.S. troops after the then-president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, was ousted in an American-backed coup.) It includes this surreal caveat:

There is recent precedent for such a force — the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti, whose blue-helmeted troops patrolled Haiti for 13 years before leaving in 2017. That mission, which involved forces from Brazil, Uruguay and other nations, was a far cry from perfect. U.N. troops from Nepal introduced a severe cholera epidemic in Haiti, and others fathered hundreds of babies born to impoverished local women and girls. There were credible allegations of rape and sexual abuse by troops.

It's telling that intervention is the first and only tool that the nebulous "international community" seeks to use, despite decades of evidence that even the most righteous humanitarian interventions are quickly co-opted by private interests and often result in disastrous, amoral collateral effects.

"Occupation and intervention has brought nothing but misery to the average Haitian person," Jemima Pierre, a professor of African Studies at UCLA who focuses on Haiti and the African Diaspora, told Discourse Blog. "It makes a mockery of both democracy and sovereignty."

As Pierre wrote in 2015, Haiti existed in a state of de facto occupation by UN troops between 2004 and 2017, dubbed MINUSTAH (the operation the Washington Post wants to repeat that was marked by a cholera outbreak and rampant sexual assault.) Even after that mission's end in 2017, the country's political future has been largely decided by a set of ambassadors from western countries known as the "Core Group." As the New York Times notes, "Interim Prime Minister" Joseph is basing his legitimacy on the support of the Core Group and openly calling for U.S. and UN support in order to keep control. So far, the U.S. appears to be obliging him, and although the Biden administration has stopped short of sending a troop deployment, it's clear that Joseph is their guy for the time being.

"For the US and the UN to immediately take this position is immediately dangerous," Pierre said. "That is also a form of intervention."

It's easy to see why immediate, direct intervention is the default position of the status quo. The United States has been directly intervening, meddling, or outright controlling the outcomes of Haiti's political future virtually from the moment that Haiti became the first slave state to gain its independence in 1804.

U.S. Marines occupied Haiti from 1915-1934, a period marked by colonial power games and frequent atrocities. From the 1950s through the 1980s, the U.S. propped up Francois and Jean-Claude Duvalier, a father-and-son dynasty that formed an authoritarian terror state with enthusiastic American support. U.S. intelligence agencies were then instrumental in deposing Aristide, Haiti's first democratically elected president, more than once; since then, the U.S. has backed a string of corrupt and repressive regimes, including Moïse's.

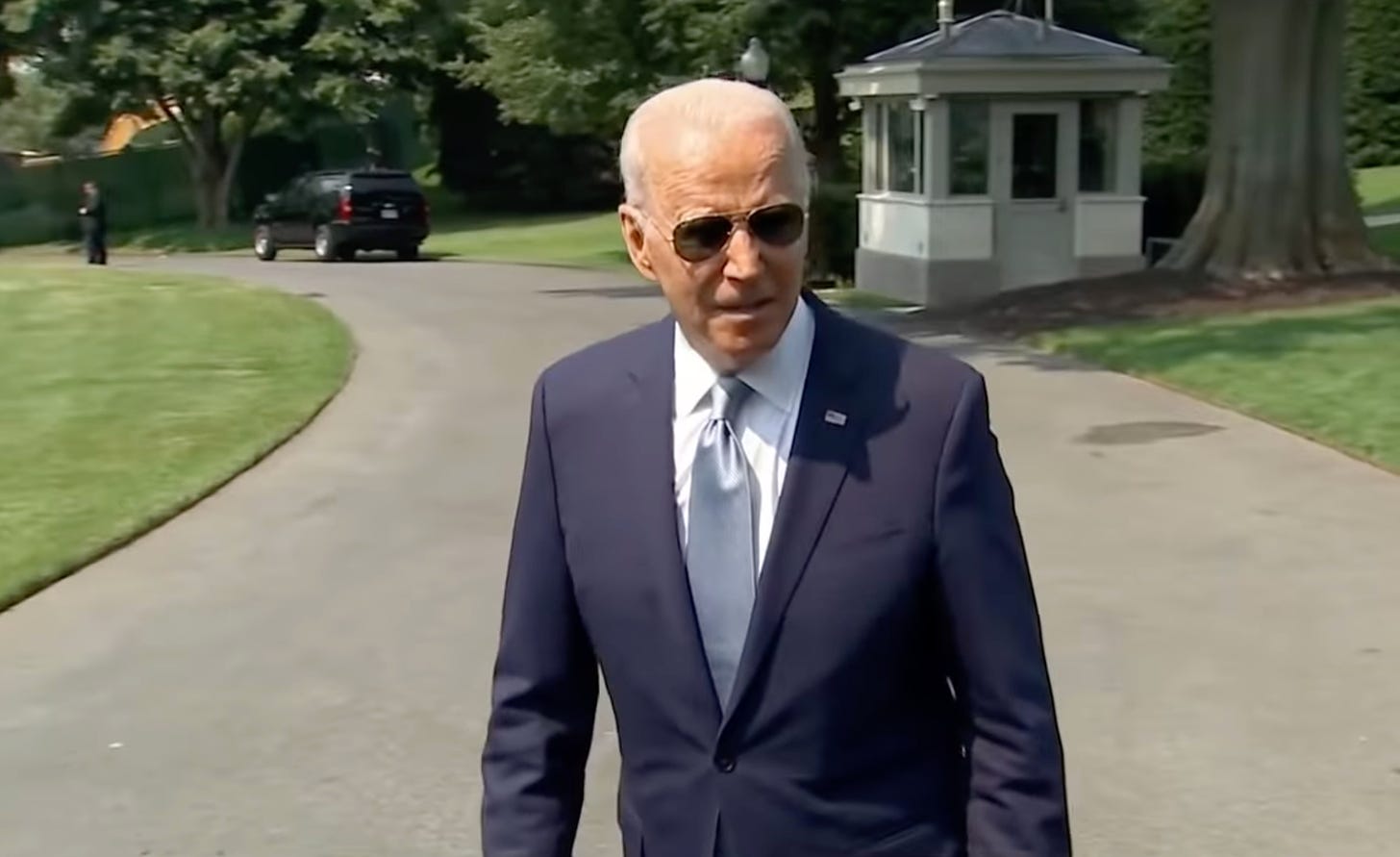

On its face, this level of American attention might seem outsized. This is a country about which Joe Biden once viciously said, "if Haiti just quietly sunk into the Caribbean or rose up 300 feet, it wouldn't matter a whole lot in terms of our interest." But the U.S. has never needed a reason beyond the principle of global dominance to justify its interventions. Haiti is there, so Haiti must be under American political, ideological, and economic control.

When the U.S. does get around to coming up with a reason to intervene in Haiti, the excuse is almost always "stability," summed up succinctly in a classified 2008 cable by former U.S. Ambassador to Haiti Janet Sanderson that was published by Wikileaks. "The UN Stabilization Mission in Haiti is an indispensable tool in realizing core USG [U.S. Government] policy interests in Haiti," Sanderson wrote. "There is no feasible substitute for this UN presence. It is a financial and regional security bargain for the USG." Sanderson claims in the same message that the USG's overarching goal is to make Haiti a successful, self-governing state, if only for the purpose of not taxing the U.S. with more unwanted refugees and immigrants.

"There’s a really racist tension to all this discussion around Haiti," Pierre said. "People expect these Black Haitians can’t control themselves. These votes go to the UN Security Council and everyone says OK -- we can't let 'chaos' happen right next to the most powerful country in the world."

But when push comes to shove, the US and international community of western states only really want stability on their own terms. In February, for instance, the U.S. backed Moïse as he struck down a plan by seven Haitian opposition leaders and other civil society members to form a transitional government in February and pave the way for new elections. The U.S. actively backing this plan would hardly be a hands-off approach, but it also wouldn't be material support for political forces in the country who want to continue ruling by decree.

The option that's almost too outlandish to mention, of course, is the most powerful country in the world agreeing to take its thumb off the scale: to let Haitians decide their future, while pursuing policies that could use its massive resources to support refugees from Haiti and the dozens of other countries it has wronged when they arrive at its borders. Instead, Haiti's U.S.-backed client government is asking for American troops to occupy the island, and thus far, the White House has refused to rule it out. Some things never change.