On late Thursday and Friday, as the depressing results came in from the union election at the Amazon fulfillment center in Bessemer, Alabama, a comparison to another bitter struggle emerged: the fight to unionize Smithfield Foods plant slaughterhouse in Tarheel, North Carolina, one of the biggest pork production plants in the world.

It took 16 years of organizing and three National Labor Relations Board elections before 2,000 workers at the plant voted to finally join the United Food and Commercial Workers union in 2008. Between the first election in 1994 and the last one in 2008, there were illegal firings, an ICE raid, and the savage beating and arrest of union activists inside the plant. There was also a decade-plus organizing effort in one of the country's most anti-union states against what is (at least now, anyway) the largest pork producer in the world. But the workers and the UFCW organizers (some of them former Smithfield workers themselves) didn't quit, and eventually, after a sustained struggle, the workers won.

In Bessemer, Amazon used all of the tools at its disposal to run a truly vicious union-busting campaign—going so far as to reportedly pressure the local post office to install a ballot dropbox on the grounds of the warehouse—and already the Retail, Wholesale, and Department Store Union (RWDSU) has said it would file objections to the result.

"This campaign has proven that the best way for working people to protect themselves and their families is to join together in a union," RWDSU president Stuart Appelbaum said in a statement. "However, Amazon’s behavior during the election cannot be ignored and our union will seek remedy to each and every improper action Amazon took. We won’t rest until workers' voices are heard fairly under the law."

The deck was stacked against workers, because it's always been stacked against workers. The PRO Act would go a substantial way towards leveling the playing field a bit more, as Brandon Magner detailed last month, but Amazon will always be able to come up with every dollar it needs and find every loophole worth exploiting in order to fight organizing wherever it can.

This isn't to sugarcoat what happened in Alabama. Getting less than a third of the vote—though it likely would've been closer if more than 500 challenged ballots had been counted—is a bitter disappointment in one of the most important and closely-watched union elections in my lifetime.

But this wasn't a foregone conclusion. It may have always been a longshot, considering the huge head start Amazon got in running up the score, but it didn't much feel like that in recent weeks, especially given the coverage of the vote. Jane McAlevey's brutal and sobering diagnosis for The Nation of all of the problems with the campaign, and the narrative around it, is an essential read.

It's worth reiterating that Bessemer wasn't just an opportunity to make a statement about Amazon or organized labor. It was about workers. This vote affected and will continue to affect the livelihoods of real people and their ability to put food on the table and a roof over their heads. The NLRB recently found that Amazon illegally fired two corporate workers who spoke out against the company's practices, and in December the NLRB found that they did the same to a warehouse worker on Staten Island. There have been dozens of NLRB charges against Amazon allegedly interfering with workers' rights to organize since the start of the pandemic, and the penalties for sustained charges are a pittance for one of the world's most obscenely wealthy companies. And it's not just Alabama where having a reputation for being a unionist troublemaker can affect your ability to find and keep a job.

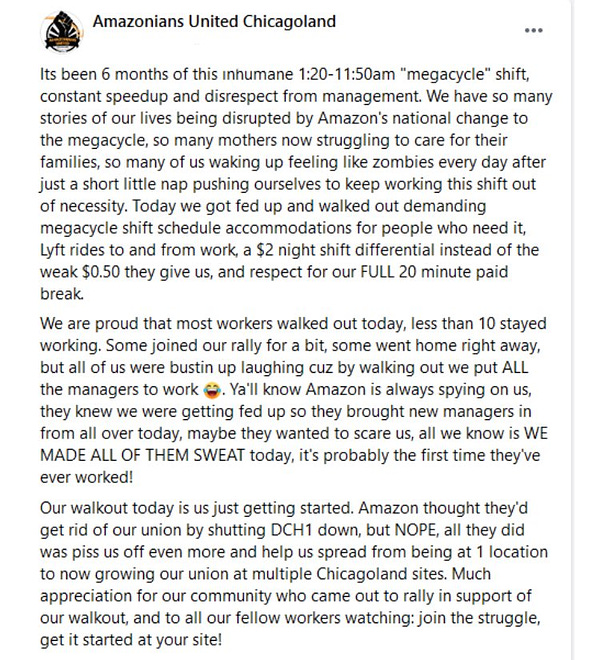

Amazon is not going to stop being a brutal, outrageously shitty employer—just this week, Amazon warehouse workers in Chicago walked out in protest of the company's "inhumane" 10-and-a-half hour overnight "megacycle" shifts. "Our walkout today is just getting started," the group said. "Much appreciation for our community who came out to rally in support of our walkout, and to all of our fellow workers watching: join the struggle, get started at your site!"

Looking forward, it's singularly important to make sure that the next time, whether the "next time" is a redo in Bessemer or a vote elsewhere, workers are put in a position to win—both the workers casting the ballots themselves and those elsewhere who are beginning to wonder if it's possible for them, too. And it's equally important for everyone to remember an essential truth: that this was neither the beginning nor the end of the fight for worker justice in this country. Amazon won today, and it could very well win tomorrow, but it's not inherently destined to win forever. "The struggle continues" is one of the oldest lines in the book, but it's also a fact.