Let Me Tell You About My Heart

Or, how some people tried to un-fuck my fairly fucked-up organ.

Let me tell you about my heart.

As I write this, it’s running at about 54 beats-per-minute, which is pretty good considering that, until a week ago, it was thumping away at more than 130, nonstop, for months on end.

I won’t bore you with the details of how I actually learned I have a bum ticker — if you want to laugh along with that particular comedy of errors, I blogged about it a few weeks ago. All you really need to know is that for nine hours last week, I served as a human pincushion in the hopes of un-fucking my fairly fucked-up organ — and it worked. Kind of.

Technically, what I’ve got is known as an “atrial flutter,” which basically means that the electrical wiring in my heart is screwed up. Instead of hammering along at a normal pace, the circuit that tells one of the chambers in my heart to beat keeps firing without resetting itself; what should be “ka-thump - pause - ka-thump” turns into “ka-thump-ka-thump-ka-thump.” Let this run for a few months on end like I did (I just assumed I was generally out of shape!) and it can seriously start to chip away at the heart’s overall functionality. In my case, part of my heart was operating at about half of what it should have been.

Fortunately, the solution is fairly simple — at least on paper. All a doctor needs to do is force a series of electrode catheters into the heart, and burn away some of the offending muscle cells — a process known as a “catheter ablation.”

“It’s bread and butter stuff,” my cardiologist explained. It turned out it wasn’t even actual surgery. No one was cutting me open and getting their hands dirty in my insides. Think of it more as being very carefully skewered — a few times in the groin at the femoral artery and once in the shoulder — and then letting your body play host to a series of red-hot death probes as they snake through the chambers of your heart. You know that scene in Hellraiser with the chains? Like that, only good for you.

“It’s a procedure,” the doctor stressed. “You’ll be home that night.”

But first, you have to swallow a camera.

When I checked into the hospital last Monday — after the requisite COVID test, temperature check, and pandemic questionnaire — I was officially slated for not one, but two co-dependent procedures. First up was a TEE — a “transesophageal echocardiogram” — to assure the doctors I didn’t have any blood clots lurking in my heart that could fuck up their ablating. This involved a squat, burly doctor shoving an ultrasound emitter down my throat and into my chest to get as detailed a picture of my heart chambers as he possibly could. The catch, unfortunately, is that he couldn’t actually put me totally under while playing paparazzi with my guts, as I needed to be able to breathe on my own during the whole thing.

Actually, let me back up here. Before I was wheeled into the TEE room by a surly nurse who explained that her entire job was to “give you goofy juice and make sure you’re alive,” I had to be shaved.

As you might expect, whenever doctors decide to fiddle around with someone’s heart there’s a lot of monitoring involved. To do that, the medical team covered my body with almost a dozen electrode stickers, all connected to a machine that bing’d every time my ticker tocked. But unlike their genteel cousins, the humble band-aid, these stickers are adhesive enough to sheer an entire layer of skin and hair right off. As a naturally hirsute guy, I had plenty of hair for those suckers to latch onto. My chest, belly, legs, shoulders, and arms all received a quick, workmanlike razoring from the unlucky orderly who spent about 45 seconds turning me into a semi-hairless checkerboard.

In any case, once sufficiently electroded, I was ready for the aforementioned “goofy juice,” which, as advertised, is when things started getting pretty goddamned goofy.

It’s a strange feeling to know with absolute certainty that you were somewhere, doing something, but not to have the slightest memory of what that something was, or where it was taking place. That, however, is exactly what the subsequent hour or so of my day was like. Every time I try to call up a specific moment — swallowing the actual ultrasound tube, for example — the best I can do is a sort of oblong memory-of-a-memory. Like I’m coming in at the wrong angle to fully pierce the amnesiac veil, and end up bouncing off into a hazy narcotic void. Have you ever tried to remember a previous night’s dream, only to realize you can’t actually tell if you’re thinking of something you actually dreamt that night, something you dreamt months ago, or something you’re just sort of making up on the spot? It’s kind of like that.

What I do know is that whatever stupefying cocktail they put into my IV — some sort of chemical combo that included, among other things, Fentanyl — worked like a charm. My memory kicked relatively — if temporarily — back into gear once I was in the recovery room for a brief interlude between procedures and began trying to explain to the nurses in my best “sure I’m stoned but I’ve totally got this” voice that I didn’t need a catheter put in my dick for the next procedure because “I’m a goddamned adult who can pee when he wants.” (I should note that I had been loudly protesting against what was, for me, the surprise inclusion of this particular part of the process for the entire day, both before and after I got the drugs. No amount of doctors using polite synonyms for “you’re being stupid” was enough.)

Somehow, I lost the argument, because pissing yourself is a real possibility in this kind of situation and probably also because I was both wrong and high out of my mind.

I don’t actually remember the nurse inserting the catheter, so much as I remember remembering it. At this point I was both coming down from the previous melange of sedatives, and getting juiced up for round two, so my faculties of both persuasion and comprehension were, shall we say, compromised. I’m left to rely on the word of my wife, who was in the room with me when the whole thing went down, so to speak. According to her, I handled it all fairly well by screaming “THIS IS NOT DIGNIFIED!” at the moment of insertion. I stand by that assessment.

Finally, it was time for the main event: the ablation itself.

Strangely, I actually do have a few specific memories from this one. Perhaps the second cocktail of sedatives was just different enough to allow for a few hazy snippets of reality to peek through. Or maybe my brain just mustered every last neuron it could spare to make absolutely sure I remembered the moment the doctor leaned over me and said, “well, I think we can fit three catheters on the right side of your groin,” as if I had strong opinions on the subject.

The actual procedure took a few hours; I remember maybe five minutes. I can definitely remember the doctor telling me to keep my head down (I was curious about what was going on down there) and have a vague impression of pressure pushing on my upper thigh. Beyond that, however, things really started to click after all the tubes had been pulled out of my (utterly pulverized) body.

It’s probably a bad sign when, even in a fading narco haze, your first coherent thought is “why is this doctor talking to me? Doesn’t he know I’m super high?” That, however, was more or less my inner monologue for a good five or six minutes while — still strapped to the procedure table, mind you — the doctor carefully explained why the ablation had been both a smashing success and a total failure. At one point he gestured to his heart, and made a clockwise motion with his finger, and then pointed at me while twirling his pointer counterclockwise. There was some rueful head shaking, and a lot of deep signs and sentences that started with “Well…”

When I was finally wheeled back to the recovery room, I was mostly coherent enough to understand that the procedure had managed to trip the faulty electrical signal that had been causing my rapid heart rate the moment the probes entered my atrium. But this somehow happened without the doctor actually dealing with the cells that were causing the problem in the first place. What’s more, my faulty circuit was somehow not where these sorts of things ordinarily are. The heart, it turns out, is actually a pretty complicated little chunk of meat.

Still, the good news was that I was finally pumping blood at a normal tempo, and would likely start recovering the cardiac functionality I’d lost to wear and tear over the past few months. The bad news was that, since the doctor hadn’t actually been able to ablate anything, there was a chance the flutter could come roaring back again at any time.

So, let’s call it a qualified success.

After wrapping my head around the fact that the past six-ish hours had been something of a wash, I was understandably pretty eager to get the fuck outta there and go back home to my own bed. Unfortunately, there was one thing still standing in my way.

What goes up must come down, and accordingly what goes in must eventually come out. At least, that’s how catheters work.

Thankfully, I still had enough painkillers roiling through my system to make the actual extraction surprisingly tolerable. Or at least, not as memorably traumatic as I imagine it would be had I been fully sober. What was less tolerable, however, was what came next: an unavoidable regaining of feeling across my body, and the dawning sense that “holy shit, I just had people fucking around inside my heart.” The combination of pain, exhaustion, and sheer weirdness was more than enough to have me dinging the call sign every 15 minutes to ask whether I could go home yet. Finally, the latest in a long line of incredibly patient nurses agreed that the only thing left to do was prove that I could pee all on my own.

Since I was, as I’d repeatedly reminded my previous round of nurses, “a goddamned adult who can pee when he wants,” this seemed like a pretty easy hurdle to clear. What I didn’t realize is that it entailed me having to very publicly piss into a plastic jug about the size of a half-gallon of milk. What I also didn’t realize is that I was extremely in no condition whatsoever to actually make anything happen. Fortunately, I was still riding a decent enough buzz from the sedatives to not really care about the first thing, and to have the stoned hubris to barrel through the second. It took a little while, but I was eventually able to shuffle down the hallway toward the nurses’ station, waving a jug of my own urine, while my open hospital gown flapped behind me, giving anyone else in the ward an unobstructed view of my full and complete ass.

As I’d previously announced, it was “not dignified.” It was, however, enough to get me the green light to finally go home. When I did, I immediately hit the pillow as soon as I’d reassured my two anxious sons that I was just fine, but please don’t hug me too hard because your heads are just high enough to hit me right where it hurts. The next time I opened my eyes, it was 18 hours later, and I was sore as fuck. Pretty hungry, too.

Which brings us to today. Incredibly, my heart rate remains good. I’m still a little sore, and my upper thigh is covered with sickly green and deep purple bruises. Still, I feel surprisingly…okay! I might have to do it all over again if, for some unforeseen reason, whatever fucked-up circuit started my heart a-flutter in the first place decides to act up once more. I don’t relish the possibility, but I’ve done it once, I can do it again. It’s not pleasant. It’s not dignified. But it’s fine.

So, that’s my heart. Now you know. Hopefully, if I have to do this all over again, I’ll win the battle about how good I am at peeing. Dare to dream.

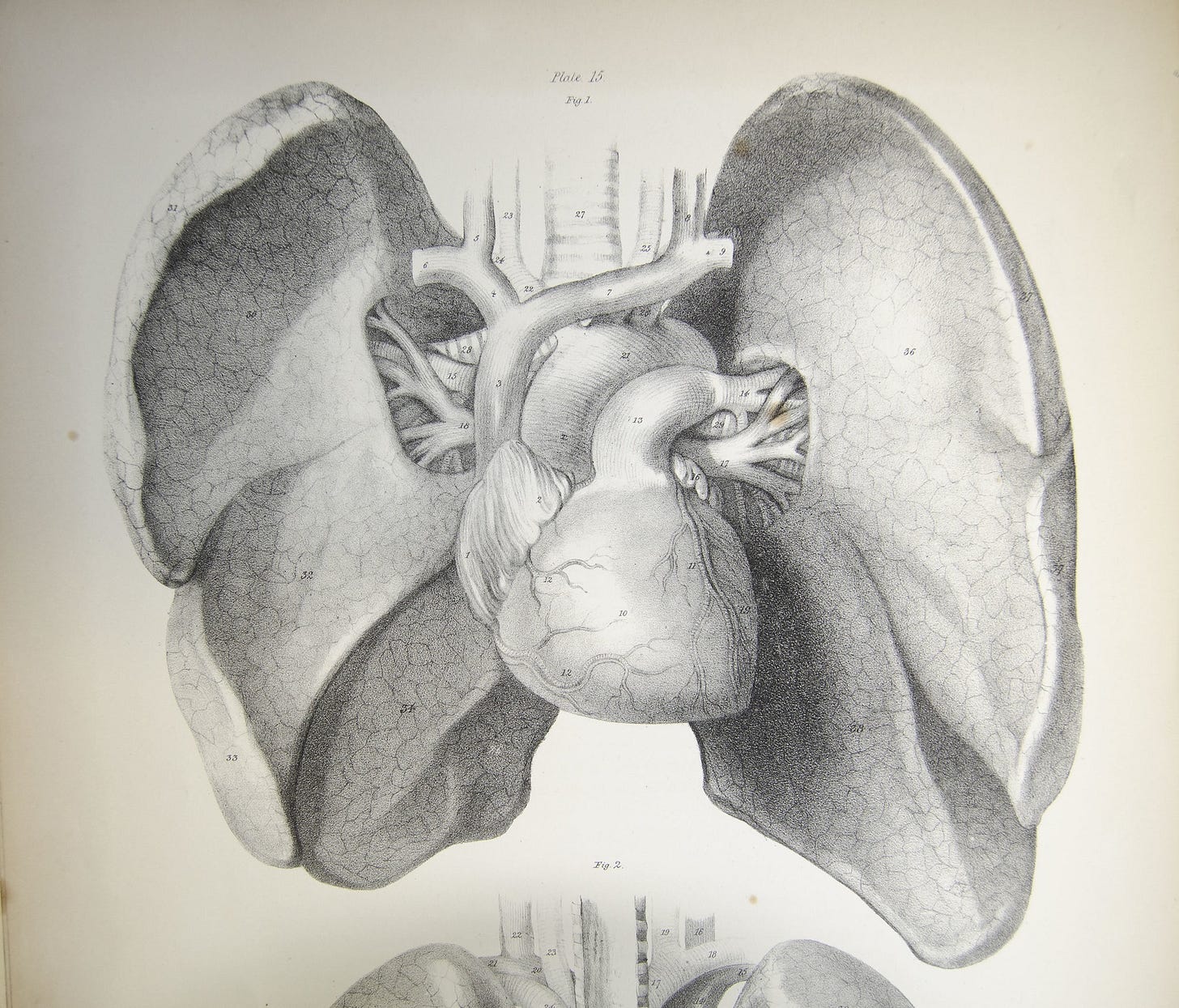

("Anatomy of the lungs and heart" by liverpoolhls is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0)

I had surgery two weeks ago for an obstruction between my kidney and bladder. It went very well and they apparently removed the catheter while I was still under. They asked me to piss before I could leave and COULD NOT MAKE IT HAPPEN. Eventually, after much straining and a BURNING desire to go home, I managed a bit of dark urine. They said I'd have to go again before I could be released. No dice.

Eventually the doctor gave me an ultimatum....I could have a catheter inserted and go home immediately or I could stay overnight with no catheter.

Gentle reader...as the doctor brought over the catheter packaging I started thinking of sounding videos and other weird dick play I've seen in porn videos and thought "well, if some people do it for pleasure how bad can it be?"

Bad

Even in the haze of my narcotics it was unpleasant. Think of what a catheter insertion is like and multiply that by 1000.

It stayed in for two days and the day of removal I was terrified. It took three seconds at the doctor's office and wasn't bad at all.

scene

after three-four years of thinking she was having anxiety attacks my wife was *finally* correctly diagnosed with afib and had an ablation that was successful. While she's had just a couple of relapse episodes in the course of 5 years some of which were terrifying and some of which were terrifying but hilarious, it mostly took. Her cardiologist says that these ablations don't last forever, but that each successive one lasts a longer time. Best wishes for long, uninterrupted periods of normal heartbeats and regular everyday hassles.