Finding My Grandparents' Graves Online

The internet works in mysterious ways.

The first time I saw my Mimi’s grave, it was in July, and it was online. It wasn’t her grave, I guess, but her grave marker — the pieces of metal soldered together that indicated to visitors that there lay Donna L., born in 1939 and died in 2013.

Mimi, and her husband, who my sibling and I called Paw Paw, were our makeshift grandparents. Mimi was my dad’s only sister, 16 years older than him, and had helped raise him when he was a child. His dad, my grandpa, died when he was still a kid, and his mom, my grandma, died in 1998. My mom’s parents, too, died a few years after, but they lived in the Philippines, and we had only met them once when my mom took us home for a summer.

So Mimi and Paw Paw, or Donna and Dan, were our grandparents. Their own grandchildren were estranged for most of the time I had with them, so the arrangement made all the more sense.

The only reason I came upon my Mimi’s gravemarker online was because I was looking for Paw Paw’s obituary. He died of pneumonia, while in a coma, in 2013. When he died, I had somehow found his obituary online and had gotten so upset at it that I emo blogged about it on my Tumblr.

I was upset because the obituary didn't mention my dad, or for that matter, me and my sibling. The obituary called him the “cherished grandfather” to his estranged grandkids, and though I think I knew that it was written by Mimi and Paw Paw’s estranged family, it was still a stinging slap in the face for a teen in mourning. I had brought up the obituary in a conversation with my mom over the summer, and just out of curiosity wanted to see if I could find it again.

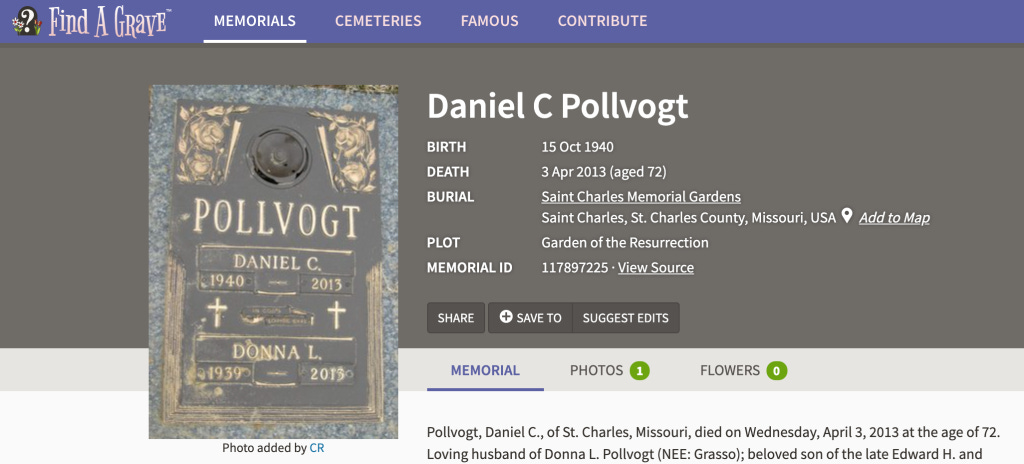

One cursory search later, and I was staring at his Find A Grave page, complete with a never-before-seen photo (by me or my immediate family, that is) of my Mimi and Paw Paw’s joint grave marker.

The two of their names and birth and death years gleaned in the profile photo, finished in antique gold against a dark, brassy plaque. Four antique roses adorn the top, flanking the grave marker’s flower vase. It was once filled with fake pink flowers, which I recalled from a visit to the plot after my Paw Paw died, when Mimi was still alive, but just a few months before she died, too. The photo, uploaded to Find A Grave in January 2015, about 15 months after her death, showed the flower vase turned over in the marker, its inverted base collecting dirt.

I’m not super familiar with Find A Grave — I don’t personally know many people who have died, and the people I do know of had died with little online presence, if any at all. But Find A Grave is where dead people go, or, really, are taken, to be remembered. The site was founded in 1995 and bought by Ancestry.com in 2013, which makes sense but feels creepy in a “DNA mapping” kind of way.

Anyone registered on the site can create a memorial for someone, and thereby becomes the “manager” for that memorial (except for famous people — those memorials are explicitly managed by Find A Grave). You can add a photo, biological information on this person, and details on the whereabouts of their grave, down to the coordinates.

You can also request photos of someone’s grave on their memorial page, which then gets sent to site members in the area. The site is mostly built by volunteers — hobbyists or people who’ve made an effort to create memorial pages and photograph graves. Find A Grave’s homepage advertises that it’s the “world’s largest gravesite collection,” with more than 190 million memorials created since its inception in 1995. (The site’s Wikipedia page says it contained 180 million burial records as of May of this year, which makes me wonder about the 10 million memorials added since then.)

This was the case with my Mimi and Paw Paw. Upon finding Paw Paw’s page, and then Mimi’s, I assumed, perhaps ignorantly, that this was some auto-generated page that had pulled Mimi and Paw Paw’s obituaries from their funeral home’s website. Then I realized that someone — someone who wasn’t me, or likely wasn’t my family — had taken that photo.

I scrolled and clicked through the pages to see what else I could learn about what led to my grandparents’ graves being uploaded to the web. They were buried in a plot called the “Garden of the Resurrection,” which seemed fitting given they were longtime Baptist churchgoers. Both of their obituaries were pulled from Baue.com, the site of a Missouri funeral home. And at the very bottom, right above the website footer, were “credits” for the memorial page.

Both pages had been created by someone with the screen name CR, my Paw Paw’s in September 2013, two months before Mimi died, and my Mimi’s on January 17, 2015, the same day that the photo of their grave marker was uploaded to both of their pages. The photo was also added by CR. I tried to think of any family I might know with those initials. But upon visiting this person’s member page, it became immediately clear that they were something of a grave hobbyist themselves.

According to Find A Grave, CR has been a member for 8 years, 5 months and 14 days. In that time, they’ve added 11,840 memorials, and managed 11,867, though I’m not sure if that includes memorials they’ve transferred to other people. They’ve added 16,110 photos, probably including pictures that aren’t just of graves, but have taken 108 volunteer photos, which I assume are the grave requests. (I looked to see if Mimi and Paw Paw's grave markers were among the requests, and they weren't.)

They’ve submitted about 30 photo requests themselves, of graves across Missouri and Ohio and the South, but much of the grave photos they’ve taken have been for people buried in the same cemetery as my Mimi and Paw Paw. According to their user history, they were a regular contributor until the end of 2017, though they last uploaded a grave marker photo in 2018, and created two memorials in March.

Their page has a bio, too, explaining that they got into this memorial hobby because they were interested in their own family history. “I was really excited when I found Find-A-Grave. I think it is a wonderful way to connect and remember those who are no longer with us on this earth,” the bio reads.

Wonderful for many, I am sure. For me, stumbling upon an image of a grave of someone I loved was jarring, and a little overwhelming. I cried realizing what I was looking at. I had no idea that this photo was out there, for years, and maybe I had even stumbled upon it years earlier — I know I had looked for my Paw Paw’s obituary before, but it had always been on another memorial site — but even then, it didn’t hadn’t clicked with me what I had found.

It was bizarre, seeing her name on the grave marker for the first time, and realizing that in the seven years since she died, I have never seen her where she’s buried. This stranger’s photo had been my only opportunity to see her, and I likely may never do it in person.

My family has no more business in Missouri, but back when we did, I saw the actual plot of land where she was buried in 2013, a few months before she died. That summer, my family drove up to St. Charlies, a city just northeast of St. Louis, to visit Mimi, who was being cared for by her son Ron, who had reconnected with his parents when my Paw Paw was diagnosed with skin cancer years before.

When we visited Paw Paw’s grave I remember her grumbling. I remember her short, petite frame of pale, freckled skin and loose clothes and a short wispy, white wig. She quietly complained and then threw a vocal tantrum about how she missed her husband.

For years, Mimi had begun to show signs of forgetfulness and difficulty communicating. It wasn’t until after his death, when my dad and uncle Tony were in Missouri, that she was diagnosed with an advanced stage of Dementia. My parents had driven up for Paw Paw’s funeral that spring, but we stayed in Texas when she died six months later. Family is complicated, and after Paw Paw died, there was little my dad could do to take care of his sister. When she died, that was it.

I have a difficult time writing this. The situation brought my family so much pain, but especially my dad. Even now, he talks about it with regret. And so seeing that photo of her grave brought so much to the surface for me, the stuff we're forced to push down because there was little room for closure.

I’m still so weirded out by this, really. A stranger had uploaded a picture of my grandparents’ grave to the internet!! And for years I had no fucking clue!!! But overall I feel grateful. Because now I’ve seen her, and I don’t have to make some big emotional road trip to Missouri to see it for myself, once my own parents are gone and I have kids of my own. Or maybe I will make the drive, and it just won’t be the emotional birthing that these trips tend to be.

This pseudo-sunny side up outlook isn't everyone's experience with the site — last year, journalist Katie Reid wrote about Find A Grave's "digital undertakers:" "a motley crew of Find A Grave superusers who have made a competition out of racking up as many memorials as possible." They work with little oversight from Find A Grave, and go to great lengths to collect memorial data, traveling internationally and mass scraping funeral home websites.

Reid wrote that the member who created her own grandmother's profile had created 114,000 memorials in his 16 years on the site. Meanwhile, a Florida superuser she spoke to had memorialized more than 3 million people. Not to rush to their defense, but CR's St. Charles-specific collection of 12,000 memorials seems almost insignificant in comparison.

I’ve tried to email CR, to ask if they’d want to be interviewed for this piece, and at the very least to see if they’d want to talk with me about their experience doing this, just for my own personal reasons. To see if they get other weird people like me in their emails, thanking them or cursing them for their online grave deposits. But I haven’t heard back, and seeing that their activity on Find A Grave has slowed to a trickle, I doubt that I will.

Which is fine — I’m not trying to trick a stranger into participating in the emotional processing of my grandparents’ deaths. This is what I have my therapist and you, our dear Discourse Blog readers, for. But it would have been interesting to hear about what a life with this hobby is like, and how one even goes about picking and cataloging and documenting the memorial of a stranger. At the very least, I hope they know I appreciate their work, even if the concept itself is on the ghoulish side.