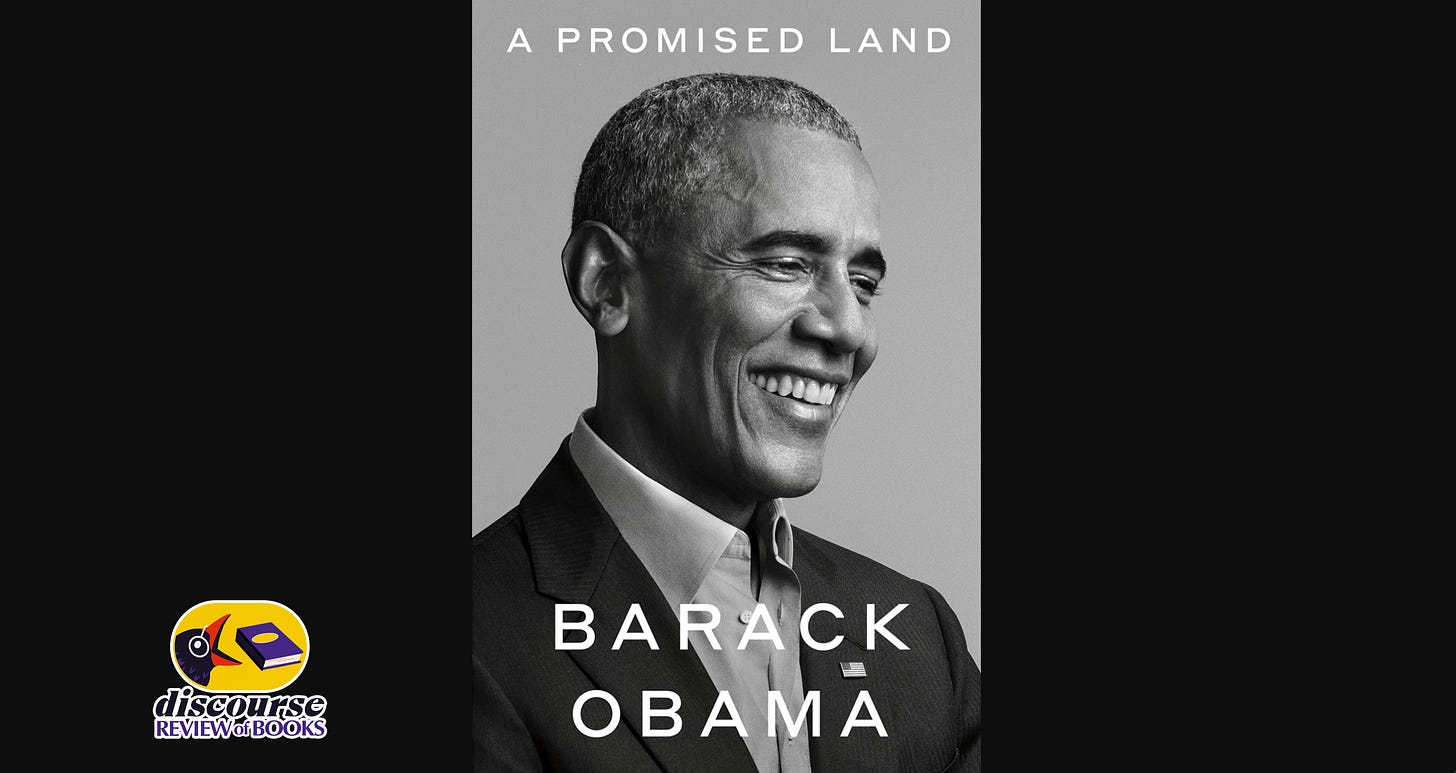

No, We Couldn't

Barack Obama's 'A Promised Land' is a portrait of change abandoned.

As a onetime liberal who drifted further and further to the left over the course of his presidency and in the years that followed, I've always viewed former President Barack Obama's political legacy to be something of an incomplete project—a worthwhile effort to change American politics that had its wings clipped first by center-right advisers like Rahm Emanuel and Larry Summers, and later by a right-wing Republican Congress. But there's something about reading Obama's own words in his 700-plus page memoir, A Promised Land, that makes it abundantly clear that he viewed these impediments to political change not as a barrier to be overcome but rather as limitations that were there for his own good, though they sometimes mildly aggravated him. What's more, he gives no indication that he would ever have done anything differently—and it is this quality above all which makes A Promised Land such a frequently frustrating read.

This may surprise some readers, since A Promised Land has been praised for its supposed thoughtfulness; the New York Times, in its decision to dub the book one of the ten best of 2020, cited what it called Obama's "remarkable degree of introspection."

It is true that, on nearly every issue he discusses at length, Obama recounts all sides of the debate and at least attempts to consider them in good faith. But though he displays a remarkable awareness of what was happening in the political discourse at the time, the chief feature of the book may be its lack of deep, intentional reflection—about both the opportunities Obama missed to be a true harbinger of change and the widespread political disillusionment to which these failures contributed. In the end, he is as certain as ever that he was right and that his critics were either cynically motivated or unhinged, in the case of his conservative enemies, or hopelessly naive, in the case of the left.

It's Obama's handling of his leftist critics that provides the most interest in A Promised Land. It's not that Obama is oblivious; throughout the book, the former president seems most concerned with engaging the left, who in recent years have challenged his legacy more than someone who repeatedly swatted the left like a fly during the course of his presidency could have reasonably expected. In the section on the legislative wrangling that resulted in the Affordable Care Act, for example, Obama reflects on being exasperated by the criticism he received about not including the public option, and not so subtly blames progressive critics for depressing turnout in the 2010 midterms, calling it the "What's the point of voting if nothing ever changes?" syndrome. In a way, he almost pines for having a conservative base instead. In contrast to the left, the conservative right under Ronald Reagan "understood that in politics, the stories told were often as important as the substance achieved," he writes.

And yet throughout the book, a recurring theme is that while Obama himself broadened the boundaries of political imagination in America, he struggled mightily with leveraging his storytelling ability—not to mention the largest popular vote win and the most Democratic Congress we'll likely see for generations—into concrete political victories.

Part of the reason is due to the deference Obama gave to his infamous brain trust of establishment politicos and hardcore Clintonites. This group sidelined his organizing behemoth, ceded virtually all political energy in America to the right for the two years he had a unified government, and played a major role in restricting the scope of the possible before it even got off the ground—quite a rap sheet when you add it all up.

Time after time, Obama quotes his advisers telling him why the American people will never accept more than the most incremental maneuvers to deal with the myriad of crises he encountered upon first taking office. "When you ask them what changes they'd like to see to the healthcare system, they basically want every possible treatment, regardless of cost or effectiveness, from whatever provider they choose, whenever they want it—for free," he recalls senior adviser David Axelrod telling him. "Which, of course, we can't deliver." Maybe Axelrod went on to explain why, exactly, they couldn't deliver on that promise, or even bother to try, but Obama notes no such explanation here.

Obama does make frequent empathetic gestures towards the left, writing that "politically and emotionally I would've found it a lot more satisfying to go after the drug and insurance companies and see if we could pound them into submission." But while he blames a host of considerations, including campaign finance incentives, for not being able to get 60 Senate Democrats on board with a bill overhauling the system, there's no attempt here to grapple with the fact that on his signature issue, he simply didn't try to put the screws to them. (Obama doesn't mention it here, but it was reported in 2010 that then-chief of staff Rahm Emanuel called liberal interest groups "fucking retarded" for the crime of trying to pressure conservative Democrats into voting for the ACA.)

There's also the familiar retreat to math—"What is it about sixty votes that these folks don't understand?" Obama remembers saying, referring to the 60-vote filibuster-proof majority needed to get the bill through the Senate. And he recalls trying to "calm folks down" about what would be in the final bill, which Obama has repeatedly referred to as a "starter home." It's an apt comparison, though probably not the one he intended—ten years later, we're still in the same fixer-upper that's only grown more dilapidated with time, and it increasingly looks like it's the one we'll die in. (If Obama was being honest, he would also admit that Obamacare was pitched to the American people as the solution to the healthcare crisis, not as a small step forward. He can't have it both ways.)

This worldview extends beyond healthcare. Obama told The Atlantic's Jeffrey Goldberg in one of his first interviews about the book that he intends it to be for "some 25-year-old kid who is starting to be curious about the world and wants to do something that has some meaning." But more often than not, A Promised Land reads like a lecture about how that search for meaning will inevitably run up against cold, hard reality.

Regarding the administration's opening pitch for the economic stimulus that would become the Recovery Act, a trillion-dollar package is floated; Emanuel emphatically shoots it down, saying, "There's no fucking way," because "any number that began 'with a t' would be a nonstarter with lots of Democrats, not to mention Republicans."

It's not mentioned that the Democrats could get a bill passed with zero Republican report, and part of the reason "lots of Democrats" would oppose an adequate passage is because Emanuel, in his role as the chair of the DCCC in 2006, purposefully sought out wealthy, self-funding, conservative Democratic candidates to run in swing seats. Many of these people would go on to vote against the ACA and most of them would be out of Congress by the time Donald Trump was sworn in.

With enough of these anecdotes and explanations, it's difficult not to wonder if the fact that Obama had a broad mandate factored whatsoever in any of these conversations, let alone what Obama's vision for change actually entailed.

In a section titled "The World As It Is," Obama fondly recalls senior adviser David Plouffe scolding a group of environmental activists: "We won't be doing anything to protect the environment if we lose Ohio and Pennsylvania!" It might as well be an entirely different Obama from the one on the campaign trail, who said after winning the Iowa caucus that the people who voted for him were frustrated that "nothing changes because lobbyists just write another check or politicians start worrying about how to win the next election or because they focus on who's up and who's down instead of who matters." Sure, politicians retreat from campaign rhetoric all of the time. But Obama promised he would be different.

And Obama goes through great pains throughout A Promised Land, from the formation of his political identity to the legislative fights that defined his first three years in office, to remind the reader that he viewed himself not as a "revolutionary soul," but an institutionalist and a moderate. The fact that he didn't push for an overhaul of the banking system and punitive measures against the bankers who ruined it, in favor of pursuing a short-term "recovery" which would prove inadequate and serve to exacerbate inequality, "revealed a basic strand of my political character," he writes. "I was a reformer, conservative in temperament if not in vision."

The book ends less than halfway through his presidency with the killing of Osama bin Laden, so we'll have to wait until the second and final volume to see how much reform Obama really thought that he accomplished and how much was left on the table when he turned the keys to the White House over to Donald Trump.

But the story through his first three years in office is one of the former president understating, perhaps not even understanding, the faith Americans put in him personally to change a politics that was not working for the vast majority of us. This isn't to say Obama could unilaterally change gravity. But whether it's because of his own temperament or the people he surrounded himself with, he was more often than not unwilling to partake in a head-on fight with the systems that he campaigned on fundamentally changing.

It's not a stretch to say that the approach and policy of the Obama administration set back the movement for progress by years. His successor was a geriatric reactionary who made much wilder promises to his own base, and the president-elect, Obama's own vice president is a creature of the Washington Obama seemed to desperately want to change. Worse yet is that Biden's central pitch both during the 2020 election and afterwards hasn't been that we can expand the bounds of the possible, but that we'll eventually learn to appreciate the scraps we're given—because, as Trump proved, it could always be worse.

Obama may have intended A Promised Land for a 25-year-old searching for political meaning. But as someone who's not all that much older, who cast his first ballot for Obama as an 18-year-old and spent some of my formative political years devoted to furthering his political project (often for zero pay), it's a good reminder of why I eventually realized I would never find the political meaning I sought in Obama's brand of liberalism—less a set of goals to be achieved than a self-indulgent journey to understand the heart of America. Consider where we are today, and you can judge for yourself whether or not that approach worked.